We have Revealed to You: Jewish Biblical Interpretation in a Comparative Context

Introduction

Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are all peoples of “the book,” that is, Scripture believed to be the revealed word of God. What defines each of these religious cultures, however, is not only their common heritage in the Biblical past but the distinctive traditions that each of them has developed for interpreting the Bible and what they believed to be its message and meaning. Indeed, it is the different ways in which they have interpreted the Bible that have decisively shaped the development of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. And all too often, perhaps, their different understandings of the Bible have also determined and complicated the tangled relations of these religious communities with each other.

Historically, the distinctive character of Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Biblical interpretation is reflected not only in the substance of their exegetical traditions but equally so in the material forms through which their authors have recorded and transmitted their interpretations. These have ranged from modes of oral recitation to scrolls to books of many different kinds. In some cases, in fact, particular religious groups consciously adopted new or different material forms for transmitting their sacred Scriptures or exegetical traditions precisely in order to distinguish and differentiate themselves from each other. In other cases, the similarity of their material forms belies the oft-repeated claims of each tradition to absolute originality and uniqueness, and demonstrates, in fact, their frequent dependence and shared qualities.

In this virtual exhibit, Fellows of the Center for Advanced Judaic Studies share with you some examples of the different exegetical traditions they have found most intriguing, and the various material forms in which those traditions have been recorded. Participating fellows have each chosen an example, written a short description of it and picked a sample illustration to go with it. Each of these examples may be found in the library of the Center for Advanced Judaic Studies or at the main library of the University of Pennsylvania (unless otherwise noted). These examples, as you will see, trace the history of these traditions of interpretation in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, and their changing material forms, from the ancient period to the early modern. And while our examples are far from exhaustive - even with the endless possibilities of virtual reality, we still could not manage to include oral tradition - it is our hope that these selections will show you both the variety and commonality of Biblical interpretation that has informed the three main religious communities of Western culture.

David Stern

Exhibit

Bible & Inner Biblical Exegesis

Facing Destruction and Exile: Inner-Biblical Exegesis in Jeremiah and Ezekiel

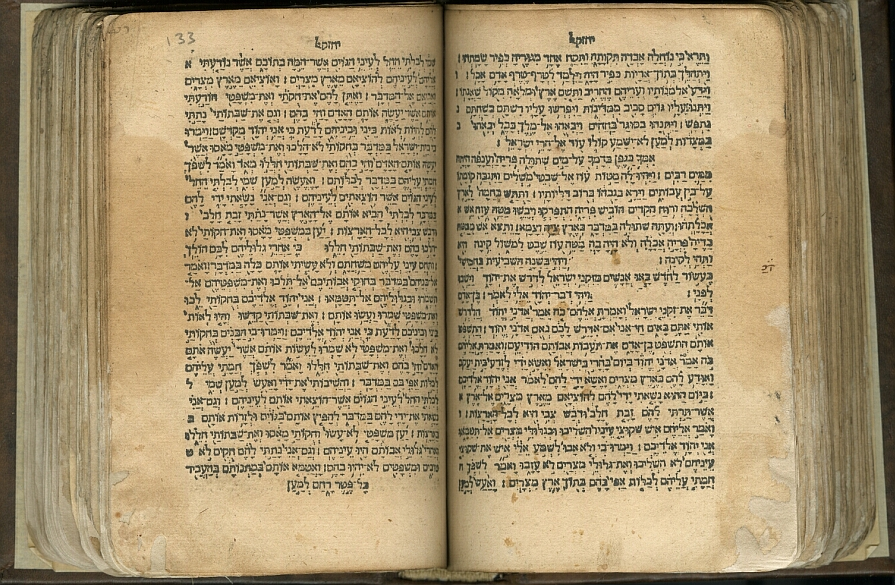

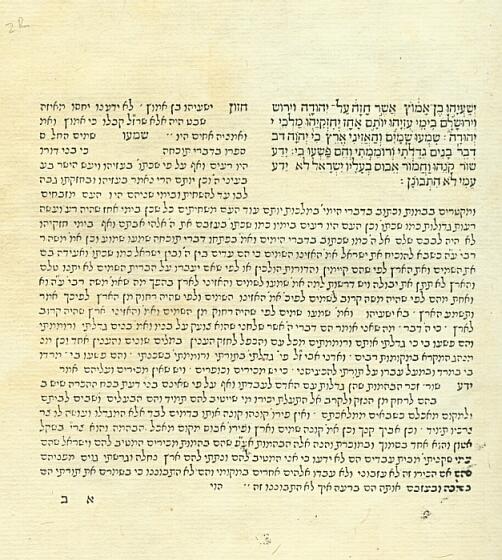

Pictured here are two passages from the Book of Ezekiel (Chapter 20) that highlight one of the major issues that preoccupied the Jews in the beginning of the Babylonian exile (597 BCE onwards). Moreover, the verses demonstrate the phenomenon of inner-biblical interpretation.

Inner-biblical exegesis and allusion suggest diverse points of view about the interrelationship between texts written over a vast geographical as well as chronological span. Scholars have identified constitutive assumptions that guided biblical authors in the exertion of inner interpretation. Three of them are considered essential for both allusion and exegesis. First, deliberate literary connections relate a later-alluding text to its earlier-source text. Second, the source text is considered authoritative and valid to the present. Third, among other reasons, the motivation of the alluding text is often to accord the present disastrous reality with the theological traditional concepts and with the historical heritage.

Examining the phenomenon of interpretation, the prophets are usually held responsible for the inner interpretation. However, inner-biblical exegesis is not restricted to the prophets at all. Focusing on one social-historical setting can illuminate the evolvement of inner-biblical interpretation. Debates and disputation-speeches in the Books of Jeremiah and Ezekiel elucidate an exegetical discourse between the prophets and their audiences, quoted as “other voices” in Jerusalem and in Babylon. Coping with kernel questions of existence in face of the destruction and the exiles, the opponents rely on different types of source texts. Nevertheless, they share one of the most constructive aspects of exegesis, namely Correlation, consisting of two contrasting phases: Analogy and Polarity. Based on different lines of argumentation, each of the quotations and their prophetical refutations treat this mode of Correlation differently. Yet the motives of the speakers and the prophets are equally exegetical. Thus, inner-biblical interpretation can be traced down in non-prophetical sources as well. This reveals a multifaceted internal exegesis already within biblical texts of the first half of the sixth century BCE.

Dalit Rom-Shiloni

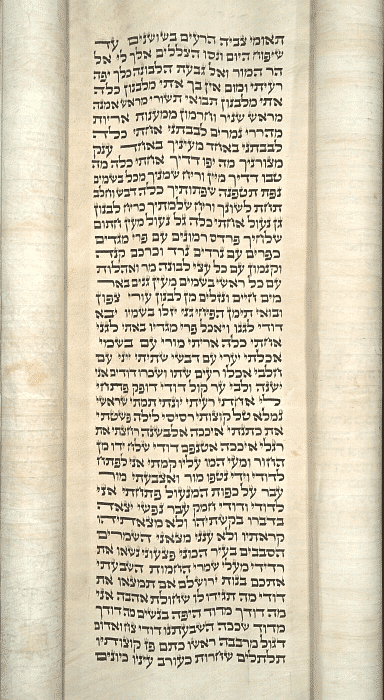

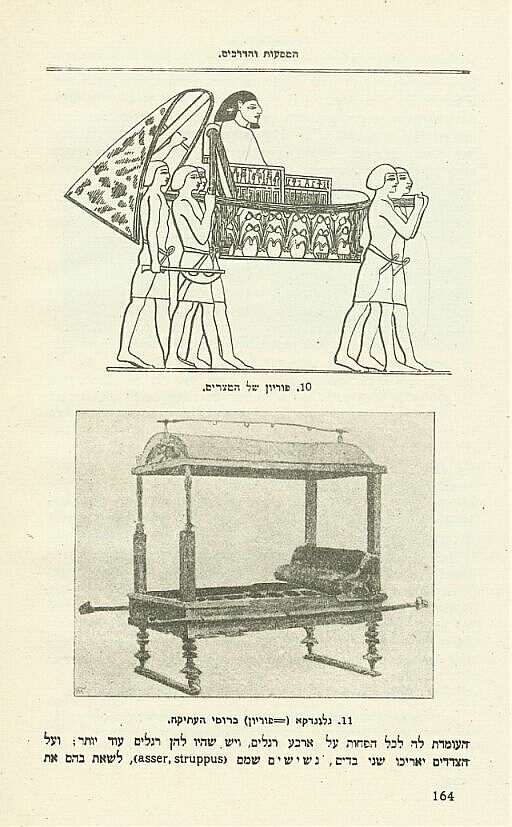

King Solomon made him a palanquin of wood from Lebanon … (Song of Songs 3:9)

The third chapter of the Song of Songs, verses 9-10, describes the nuptial bed of King Solomon, known as the palanquin (Apirion). Some scholars claim that this song was composed in honor of King Solomon’s marriage to the daughter of a foreign king, possibly Pharaoh’s daughter. If this assumption is correct then this song embodies the oldest song in the book of the Song of Songs; it forms the Book’s nucleus and all the other poems were assembled and composed around it.

The Song of Songs Rabbah (an exegetical Midrash, that comprises sayings of sages that lived in the land of Israel, between the first and fourth century CE, although it was redacted at somewhat later period) on these verses introduces a series of five allegorical interpretations on verses 9-10. Each interpretation (Petira) represents a complete and systematic allegorical exegesis for these verses. The palanquin is used as an image to following themes: the Tabernacle, the Ark, the Temple, the Creation of the World and the Throne of Glory.

Tamar Kadari

Syriac Biblical Exegesis

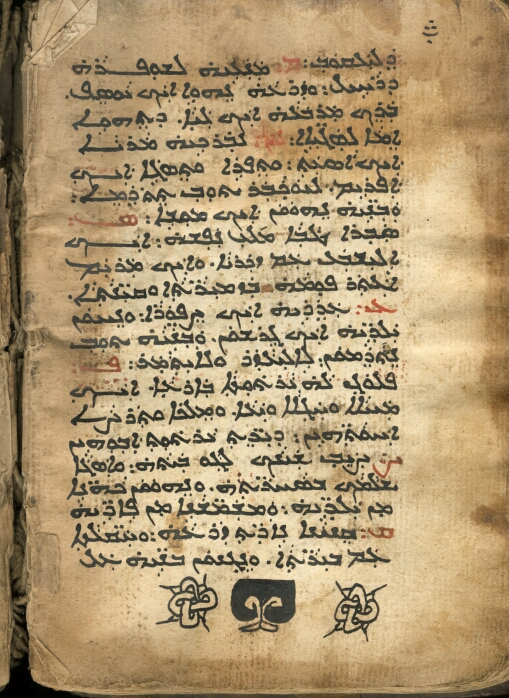

The Syriac language, a dialect of Aramaic, is the liturgical language of the Christians of the East. Beginning in the third century at least Syriac-speaking Christians flourished in Mesopotamia. The various communities lived along the ever-changing borderlands between the Roman and Persian Empires and later between the Byzantine and Arab empires. They thrived and grew amidst the cross-cultural admixture of the late ancient Near East.

According to tradition, Edessa and its king were converted to Christianity in the second century by Addai (Thaddeus?) one of the 70 disciples of Luke 10.1 This history is recorded in the Syriac treatise, the Doctrine of Addai. Whether this trajectory is accurate or not, the Bible was soon translated into Syriac at Edessa. The Peshitta of the Old Testament was probably first translated from the Hebrew for the Jewish community, but it eventually became standard for the Christians. The New Testament gospels circulated in several versions, one of which, the Evangelion da-Mehallate, was a homogenization of the four gospels into one.

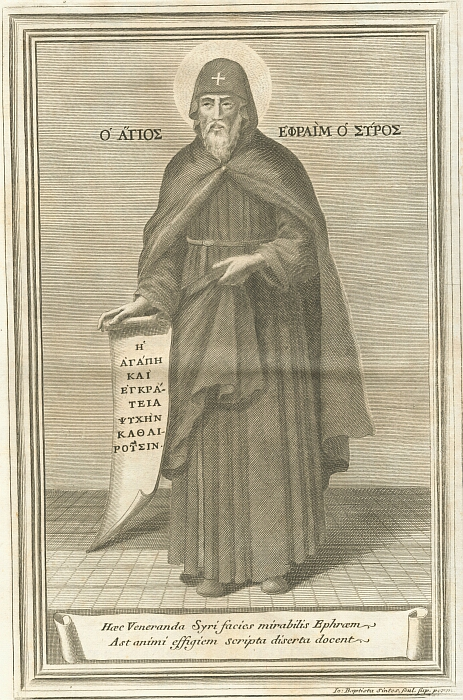

From the fourth-century onward the Christian community produced many homiletic, exegetical and liturgical works. The fourth-century produced the likes of Ephrem Syrus who was known for his lyrical poetry and extensive biblical commentaries as well as community leadership. Ephrem’s older contemporary Aphrahat the Persian Sage interpreted biblical passages in unique (among fourth-century Christians) ways. His Persian-Mesopotamian Semitic milieu, minimally influenced by the developing Greco-Roman Christian tradition, afforded Aphrahat the opportunity to innovate in his biblical readings. Yet, much of his homiletic writings reflect similar patterns in the contemporaneous rabbinic writings illuminating the cross-cultural matrices of the late ancient Near East.

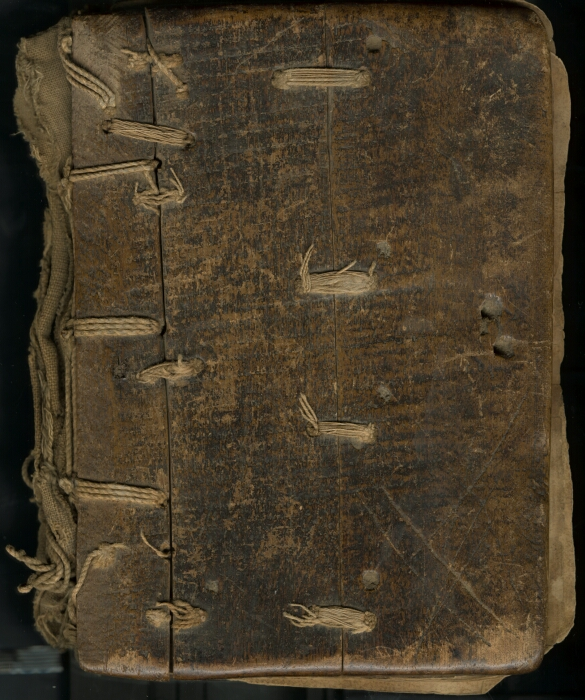

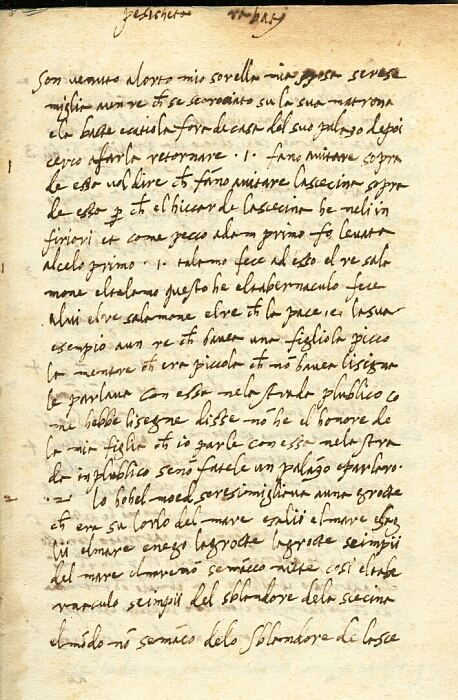

Syriac writing continued to flourish into the Arab period. Yet as Arabic became the lingua franca of the Syriac Christian community in the Arab lands, Syriac was relegated mostly for liturgical uses. The page of manuscript displayed here is from an 18th century Takhsa damkurayya, a written betrothal agreement. This manuscript is written in the Nestorian hand, one of the three standard Syriac scripts.

Naomi Koltun-Fromm

The Bible as Read: The Idea of Election in the Ritual of Scriptural Reading

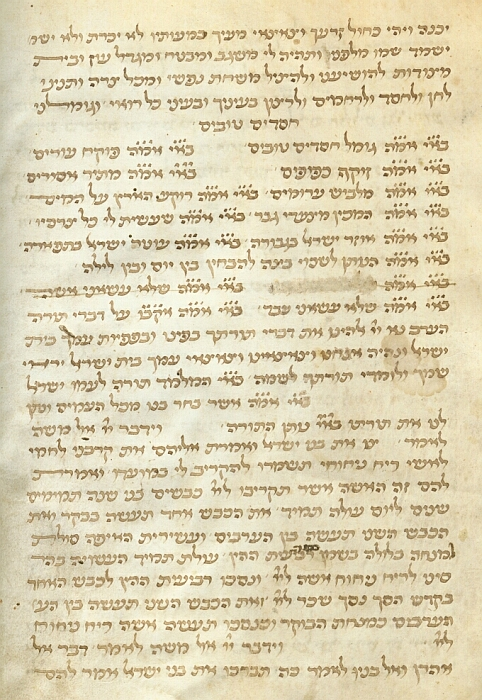

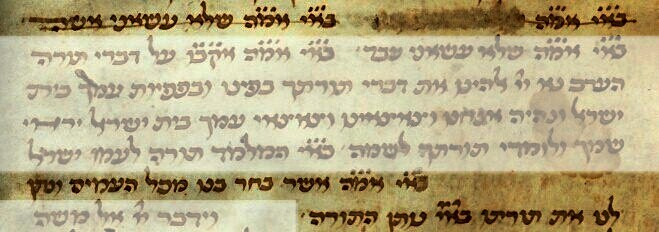

The blessings recited before and after the scriptural reading defines the reading as something separated from everyday life, as a ritual. In the blessing which is recited before the Torah reading, we meet the idea of the election of Israel:

“Blessed are you, Lord our God, King of the universe, who has chosen us from all peoples and given us the Torah” (Babylonian Talmud, Berakhot 11b)

Scholars explain that this blessing emphasizes the connection between the election of Israel and giving the Torah. The election of Israel was implemented by giving them the Torah. But why is the idea of election is mentioned here, in the context of reading the Torah in public? What role does this blessing fulfill in this specific liturgical context?

It appears that the election of Israel in the Torah blessing is connected to the “democratization” of the public reading in the rabbinic custom. In ancient sources where rituals of Torah reading are found, the reader is always a priest or the political leader. In “Hakhel” gathering, at the festival of Sukkoth after the seventh year (the Shemitah), the king is the one who reads from the Torah (Deuteronomy 31,10-13; Mishnah Sotah 7,8). In the description of the public reading in Nehemiah 8, the reader is Ezra the priest, and in the description of the Torah reading after the service of the high priest at the Day of Atonement, the reader is the high priest himself (Mishnah Yoma 7,1). The same picture rises from Philos’ description of the Torah reading on Saturdays (Hypothetica 7.12-13). Compared to that we find a very different picture in the rabbinic literature. According to the rabbinic sources every Jew (in principle) may read the Torah, not only the priest or the leader (Tosefta Megilah 3,11). It appears that the idea of election of Israel that mentioned in the Torah blessing is not an abstract theological idea. It is rather connected to the performance of scriptural reading. In order to justify the active participation of lay people in this worship, which is not trivial at all, the reader mentions in his blessing that God elected the entire people of Israel and gave them his Torah.

Adiel Kadari

Dead Sea Scrolls

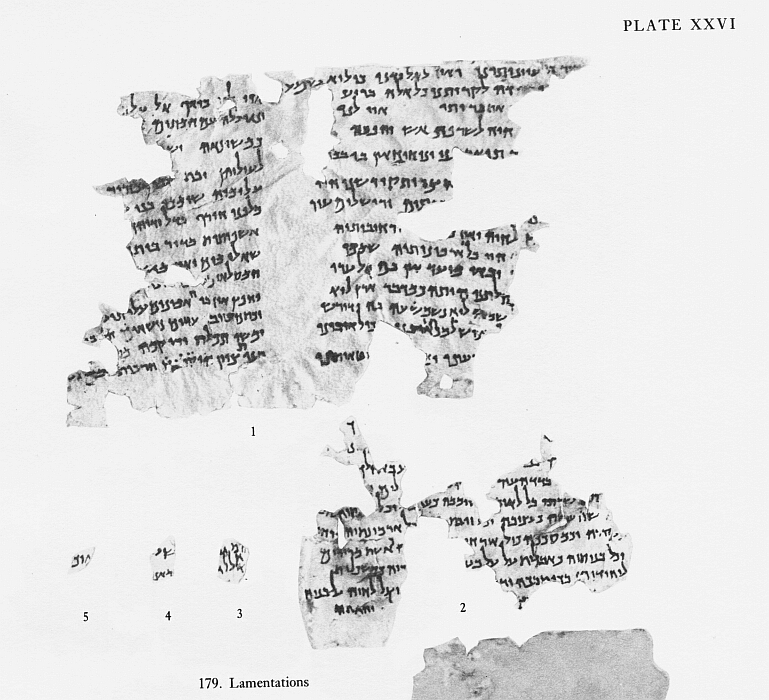

Lamentations at Qumran

More interesting than the recent controversies surrounding their publication are the Dead Sea Scrolls themselves, especially what they tell us about how the Bible was used and interpreted by this Jewish community at Qumran. All the books of the Hebrew Bible except for Esther have been found among the Scrolls, most in multiple copies, and several with commentaries (pesharim). Among the most popular books were Genesis, Deuteronomy, Isaiah, and Psalms, but verses from all the books could find their way into the community’s own writings, in the form of proof texts, citations, and allusions. The allusions are a particularly subtle but effective way to make the Bible relevant to a contemporary situation.

Such is the case with Lamentations, a book commemorating the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BCE. Many verses from Lamentations were woven throughout two lament-like poems from Qumran giving voice to the community’s sense of alienation from other Jews. To the people at Qumran, Jerusalem was still destroyed (since they rejected as being corrupt the Jerusalem priesthood and worship at the Second Temple). They likened their Jewish opponents, in the war of words over biblical interpretation and religious doctrine and observance, to the Babylonians of old, who were responsible for Jerusalem’s destruction. They felt besieged, mentally and spiritually, if not physically, no less than their ancestors in 586. The people at Qumran were, in their own eyes, the true heirs of biblical Israel, and their use of the Bible reflects and supports that belief.

Adele Berlin

Rabbinic Midrash & Patristic Exegesis

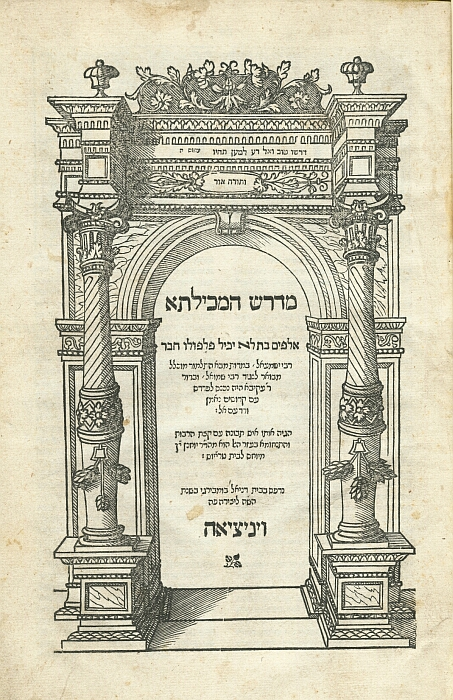

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael

In recent years scholars have revised their understanding of the place of the rabbis in the first three centuries of the Common Era. Where rabbinic texts were once assumed to represent a sort of Normative Judaism of the post Temple era, and the rabbis to be the leaders of the Jewish community living under Roman rule, we now understand the early rabbis to have been a small and decentralized “movement,” claiming few adherents outside their own limited circles. This shift in historical thinking means we need to return to these texts and read them anew. The text above is part of an introduction to the civil laws collected in the Mekhilta (Tractate Mishpatim or Nezikin) and worries about the status of rabbinic legal authority in a Roman world. It is one of the texts that invites the reader to re-imagine the group that composed this midrash to be marginal, but ambitious, asserting an exegetical authority able and willing to lead the Jewish community.

Natalie Dohrmann

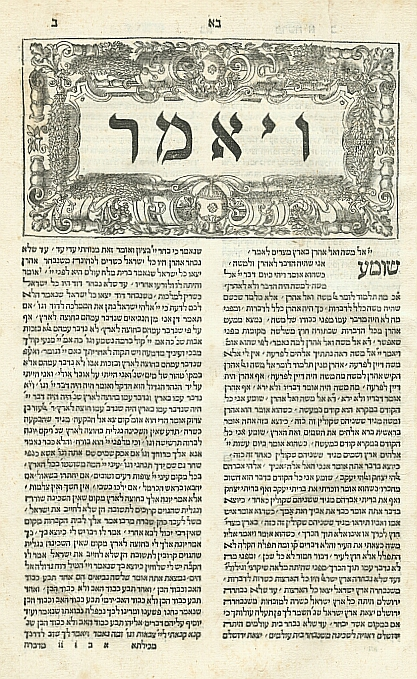

Patristics and Portraiture? Typological Interpretation

Dan Sheerin

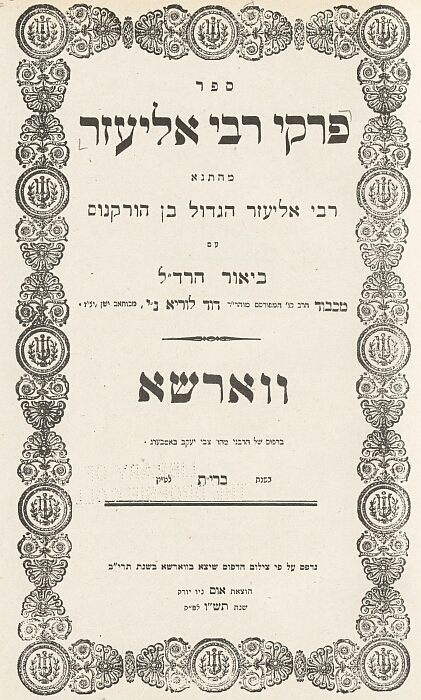

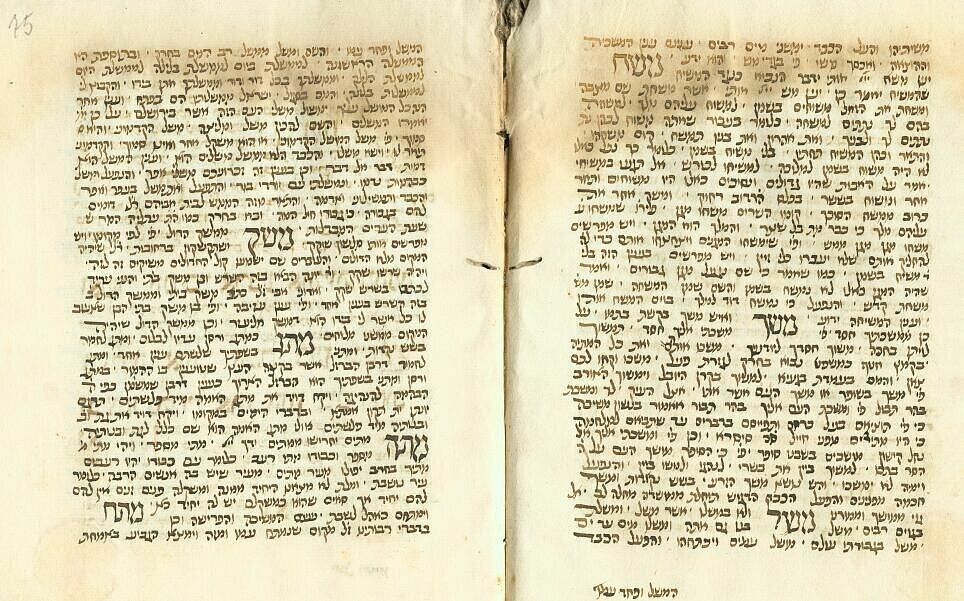

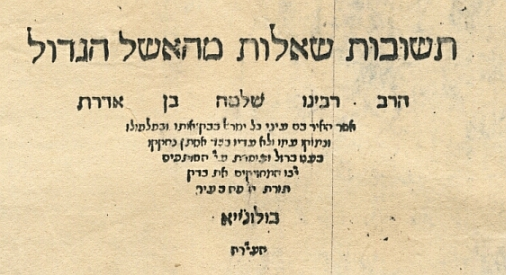

The Pirke de-Rabbi Eliezer

This eighth-century midrash was attributed to R. Eliezer b. Hyrcanus and frequently called Baraita de-Rabbi Eliezer in medieval rabbinic literature. This attribution, its mystical air and the way that the midrash is dealing with subjects of halakhah built up its popularity. Many manuscripts have been preserved, and it was reprinted time and again after its first publication in Constantinople 1514.

The most popular edition of the midrash, itself reprinted many times over, is the Warsaw 1852 with a commentary by R. David Luria, and with lacunae due to censorship. A semi-critical edition by C. M. Horowitz was published in Jerusalem, 1972 as a facsimile, and is based on the Venice 1544 edition.

Jacob Elbaum

The Pesikta Rabbati and Christian Hebraism in Italy

Seth Jerchower

Medieval Jewish, Christian & Islamic Exegesis

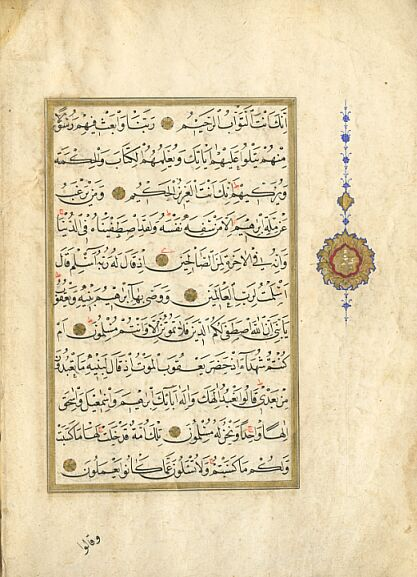

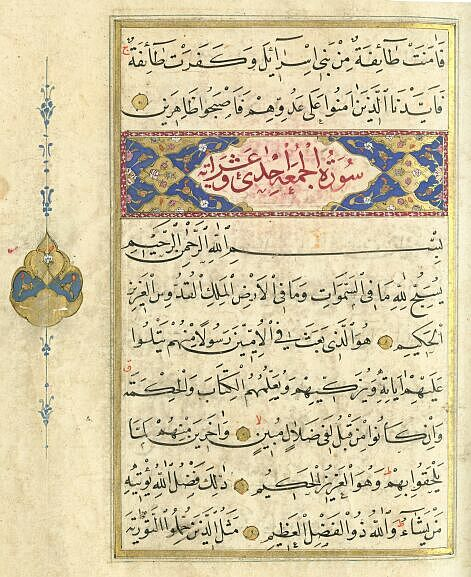

Scripture in Islamic Tradition

For Muslims, as for Jews and Christians, the notion of scripture lies at the core of faith. That a common scriptural heritage links all three faiths is already announced in the Qur’an, which refers to followers of the shared Judaeo-Christian tradition with the phrase “ahl al-kitab” (“people of the Book,” e.g., 3:199). The Qur’an is, of course, “the Book about which there is no doubt, guidance for the God-fearing” (2:2). But the Qur’an also suggests that it is only the most recent iteration of the very same “the Book” on which its sister faiths are founded. God says “We brought the family of Abraham the Book and wisdom” (4:54). God also “revealed the Book which Moses brought, as light and guidance for the people” (6:91). Jesus receives from God, “the Book, wisdom, the Torah, and the Evangelium” (5:110). God’s message reaches its final form with Muhammad, whom God sends, following in the path of these biblical figures, as “a messenger” to “recite His signs and teach … the Book and wisdom” (2:129).

Joseph Lowry

Liturgy and Music in Byzantium

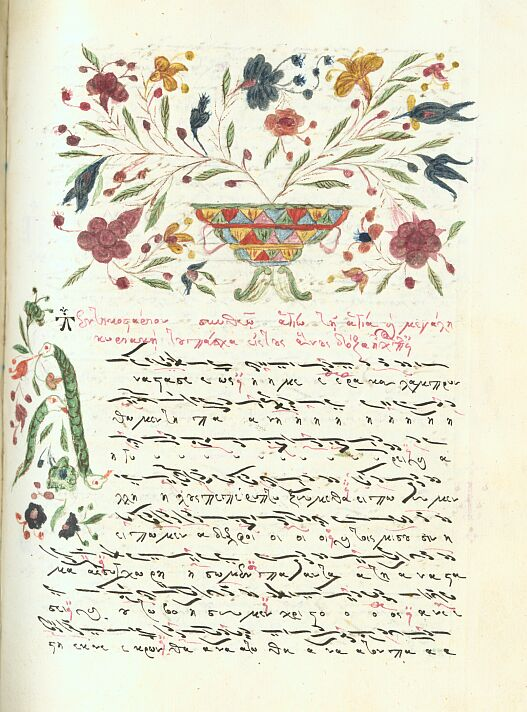

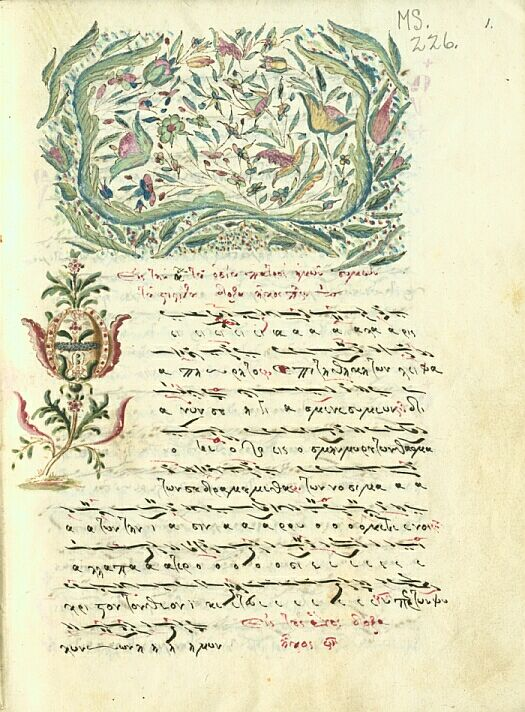

An 11th C. revision of the post-iconoclastic controversy Stikherarion (with sanctoral additions and deletions subsequent to those controversies) continued in use until the 15th century, when a similar revision occurred, and when more highly developed (ornamented and melismatic; Neo-Byzantine notation) melodies replaced the previous simpler, syllabic notation. Several hundred stikheraria survive, each normally containing about 2000 Stikhera.

According to the dedicatory colophon [97v], RAR Ms. 226 was collected and arranged by Iakovos [James] the ‘Protopsaltis’ [Head Chanter] and completed by George of Smyrna on 25 October 1800. Written on glazed paper in a precise secretarial cursive with a ferrite black inking for the text and Neo-Byzantine musical neumes written above the text, and a cuprite rose-red inking for rubrical and modal superscriptions, Capitals and leads to inter-stikheral verses.

The size, abridgement and decorative illumination of RAR Ms. 226 may point more to private usage rather than as part of a formal ecclesiastical aumbry. Such privately owned volumes became increasingly popular in the late 15th C and often functioned in the same manner as private books of hours did in the Latin traditions of the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

Josef Gulka

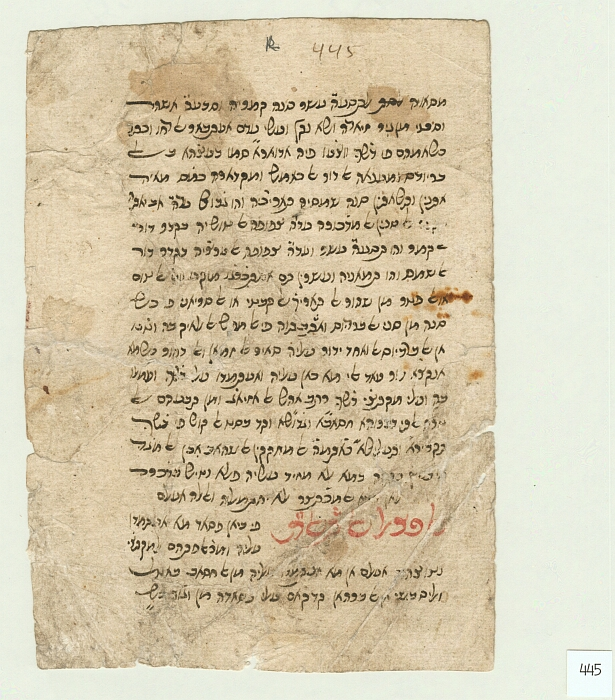

Judeo-Arabic Polemics

The Geonic period (9th-11th centuries) opens an entirely new chapter in the history of Jewish learning and Jewish culture. New activity in Halakhic monographs, Biblical exegesis and religious philosophy, starts suddenly, from nothing as it were, with very little antecedents to rely on. The beginning of this new chapter is coupled with a most fundamental cultural change, namely the emergence of Judeo-Arabic culture. Jews adopted the Arabic language, indeed Arab culture, for all needs and purposes. This important change affected all areas of literary activity, both religious and secular, with the exception of liturgical poetry. As a result of this change Jews shared the same language with all other inhabitants of the political system of Islam - Muslims, Christians (a very large and conspicuous community within the boundaries of Islam) and members of other faiths. Socially it involved all segments of the Jewish population, including the highest echelons of Jewish spiritual and cultural leadership of the largest communities at the time. The importance of this change cannot be overestimated, as it brought Jewish spiritual activity in direction contact and interaction with the cultural environment at large (including Islam, Christianity and the heritage of Classical philosophy and sciences). It should be mentioned though that as a rule Judeo-Arabic (with the exception of several hundred Karaite Medieval manuscripts) is written in Hebrew script (like some more recent Jewish languages). This has constituted in some measure a cultural divide between Jews and members of other faiths. Judeo-Arabic has been used by Arabic speaking Jews until the 20th century.

The Geonic period witnessed also the most important development in the history of Jewish sectarianism during the Middle Ages, namely the schism between Rabbanites and Karaites. In principle the Karaites rejected (and still do to this day) the authority of the Rabbinic tradition in favor of independent interpretation of the Bible. In practical terms this led to the development of an independent system of commandments and prohibitions. The differences between them and other Jews were most evident in the areas of communal and family affairs - liturgy, calendar, holidays and laws of marriage.

This is the background to the emergence of a rich and varied polemical literature in Judeo-Arabic, aimed by Jews against other faiths, and within Judaism between Karaites and Rabbanites. In fact every Karaite Halakhic or exegetical work contains extensive polemical sections.

Haggai Ben-Shammai

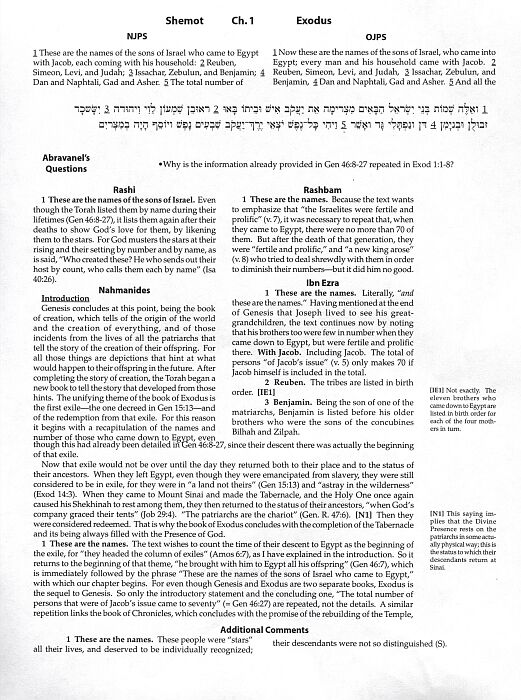

Rashi: Commentary and Plain Meaning

![Fig. 1: Fol. [1a] with commentary Genesis 3,8 (lines 9-11): "There are Many aggadic Midrashim, and our Rabbis have previously set them in proper order in Genesis Rabbah and other Midrash collections. However, I have come for the plain meaning of the biblical text and for the Aggadot that settle the words of the Scriptural text in their proper order."](/legacyexhibits/assets/images/AndWehaveRevealedtoYou/img_20.png)

![Fig. 2: This is the first printed Hebrew book to bear a date, (10 Adar 235 = 17/18 February1475). These images come from the facsimile of the only known close to complete copy, currently housed at the Biblioteca Palatina in Parma (ed. by J. Joseph Cohen, National and University Library, Jerusalem, [1969]). The Parma copy lacks the first leaves, and fol. [1a] begins with the comment to Genesis 3.4, "Thou shall surely not die.", the serpent's reply to Eve.](/legacyexhibits/assets/images/AndWehaveRevealedtoYou/img_19.png)

Although the first dated printed edition, the work is neither the first edition of Rashi’s commentary, nor the first book to be printed in Hebrew. Between 1469 and 1472 three brothers, Obadiah, Menasseh, and Benjamin of Rome, were active as the first Hebrew typographers. Six works are positively known to have come off their press, among which was the first, albeit undated edition of Rashi’s commentary. Nonetheless in 1475 edition Abraham Garton created and employed, for the first time, a typeface based on a Sephardic semicursive hand. It was this same style of typeface that a few years later, when commentary and text were incorporated onto one page, would be used to distinguish Rabbinic commentary from the text proper. Ultimately, this typeface would be known as “Rashi script.”

Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac of Troyes (1040-1105, known by the acronym Rashi [Rabbi Solomon Yitzchaki]) is acknowledged as the biblical commentator par excellence of the Jewish exegetical tradition. Rashi spent his early years in Troyes and then went to the rabbinical academies of Worms and Mainz where he drew upon the classical rabbinic sources that had been transmitted from both the Babylonian (Islamic) and Palestinian (Eretz Yisrael and Byzantine) traditions.

Rashi wrote commentaries on the entire Hebrew Bible (except Ezra-Nehemiah, Chronicles and Job). One of his fundamental principles was to balance the lexical boundaries of the biblical words or phrases against a variety of potential interpretations from rabbinic literature. He described his approach in the following way: “There are Many aggadic Midrashim, and our Rabbis have previously set them in proper order in Genesis Rabbah and other Midrash collections. However, I have come for the plain meaning of the biblical text and for the Aggadot that settle the words of the Scriptural text in their proper order.” (Genesis 3:8). Rashi used the Hebrew phrase unique to his writings, Peshuto shel Miqra, to describe his goal. A discerning reader of Rashi’s commentaries can observe his sensitivity to the Christian environment. The initial comment on each of the Five Books of Moses presses the argument that each book is a continuous narrative of God’s affection for the Jewish people. In his commentary on the Psalter there are several references to a Teshuvah le-Minim (a response to the Christians) that refute a typological reading of the Psalter as prophesies of Jesus Christ and the Incarnation. The commentaries on the prophetic books also have indications that Rashi “answered” the Christians [Ezekiel 1:3], and the eschatological visions indicate his sensitivity to the suffering of the Jewish people in the exile. The biblical commentaries of Rashi influenced his immediate successors in the Northern French Jewish academies such as his younger colleague Joseph Kara, and his grandson Samuel b. Meier. In addition to his influence on the Jewish exegetical tradition, Rashi’s commentaries appear to have been a source for the scholars at St. Victor Abbey in Paris such as Hugh and Andrew. Furthermore, the Franciscan Nicholas of Lyre (1270-1349) made extensive use of Rashi’s commentaries and thereby influenced the work of Martin Luther and other scholars of the Reformation.

Michael Signer

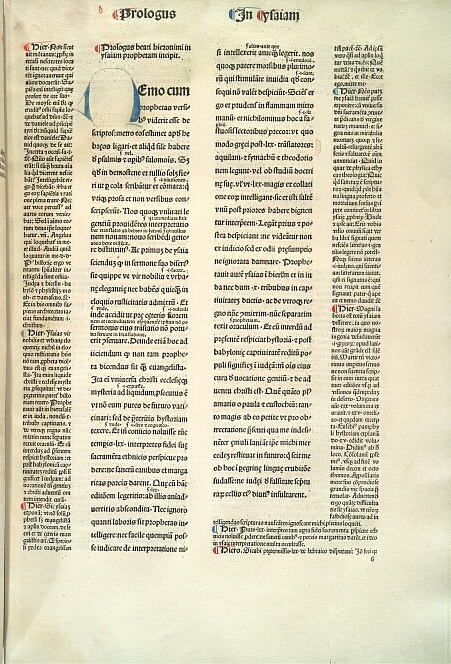

The Glossa Ordinaria and the Development of Layout

Gloss (Gk. glossa, Lat. glossa, tongue, speech) is an interpretation or explanation of isolated words. To gloss is to interpret or explain a text by taking up its words one after another. In Canon law, glosses are short elucidations attached to the important words in the juridical texts, which make up the collections of the “Corpus Juris Canonici” (q.v.). But the term gloss is also given to the ensemble of such notes in any entire collection, e. g. the Gloss of the “Decretum” of Gratian, of the “Liber Sextus”, etc. These brief notes, at first inserted between the lines, soon overflowed the margins, and became copious enough to form a framework, intertextually and physically, within which the real text was enshrined, as may be seen by an examination of ancient manuscripts and certain editions of the “Corpus Juris Canonici”. Moreover, later glosses were of such ample proportions as to become at times small commentaries containing discussions on the opinions of previous canonists. As each master added his own gloss the notes began to swell in volume; but care was always taken to indicate the particular author by placing a significant abbreviation after his gloss, thus: Hug. or H. (Huguccio); Jo. Fa. or F. (Joannes Faventinus), etc. Gradually this mass of glosses took on in the schools a permanent form, a necessary condition to its usefulness in teaching; and became a kind of secondary canonical text, less authoritative, of course, than the original, but supplying material for oral commentary. Thus arose “ordinary gloss” (glossa ordinaria), endowed with a certain authority. While this authority was not indeed official (as though it were actually the law on the point), it was nonetheless real. It represented not only the opinion and authority of the individual canonists and commentators who wrote it down, but also expressed the summa of current teaching at the time. This glossa ordinaria model for an authoritative chain of interpretive citations found its widest distribution and application in the genre of scriptural commentaries, either on individual books the Bible, or on the entire Scriptural corpus. These glossa ordinaria became, in fact, the chief source for teaching, preaching and studying the Bible in the middle Ages.

Josef Gulka

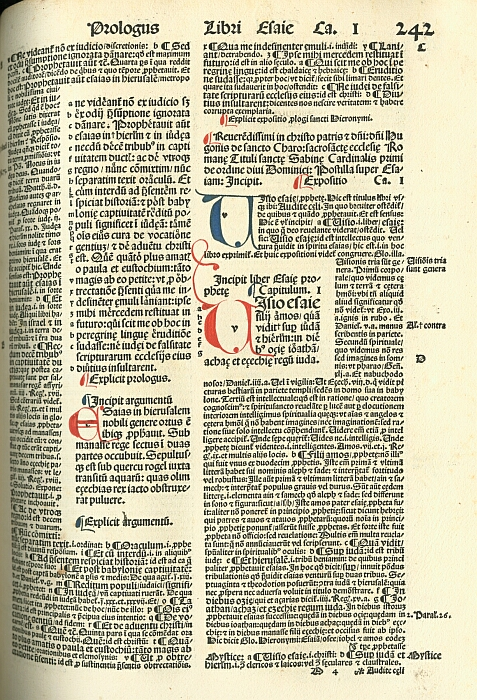

Nicholas of Lyra and Rabbinic Exegesis!

img_18.png Nicholas of Lyra - Franciscan, Hebraist, and biblical exegete - turned to the Hebrew Bible and rabbinic commentaries more extensively than any other medieval Christian Bible commentator. The interpretations of “Rabbi Salomon” (Rashi) and other “Hebrew doctors” are cited on almost every page of Nicholas’s Old Testament commentary and with remarkable frequency in his New Testament commentary as well.

Nicholas was drawn to the Hebrew text (and to rabbinic exegesis as authentic interpretation of Hebrew text) in his effort to establish a clear reading of the literal sense of the Christian Bible. Because he allowed for metaphor and multiple layers of meaning within the literal sense of Scripture, Nicholas was able to make use of a wide range of rabbinic interpretations.

While Nicholas was quick to challenge Jewish interpretations that he believed contradicted Christian doctrine, he was just as likely to abandon longstanding Christian interpretations if he thought the Jewish approach more likely or “reasonable.” Drawing perhaps on a lost tradition of Rashi manuscript illustration, Nicholas frequently used figures to juxtapose Jewish and Christian exegesis on specific passages, as here in Exodus 25:10-21. Nicholas describes the arrangement of the rings, staves, and cherubim upon the ark according to Christian tradition and according to Jewish tradition as presented by Rashi. In the midst of his discussion, Nicholas interrupts himself to direct his reader’s attention, saying “so that the above said things may be understood more easily, I have described them in a drawing.” As is often the case, the drawings help support Nicholas’s contention that Rashi’s interpretation is more reasonable than the traditional Christian view.

Deeana Klepper

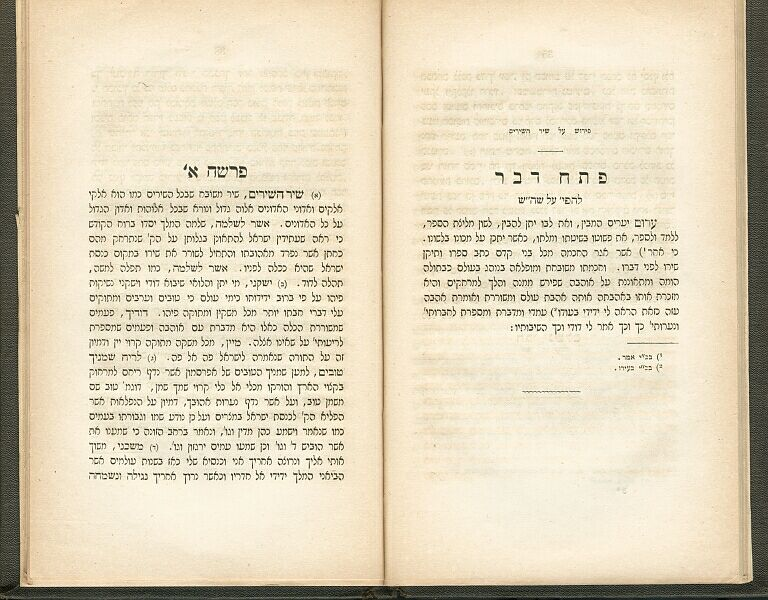

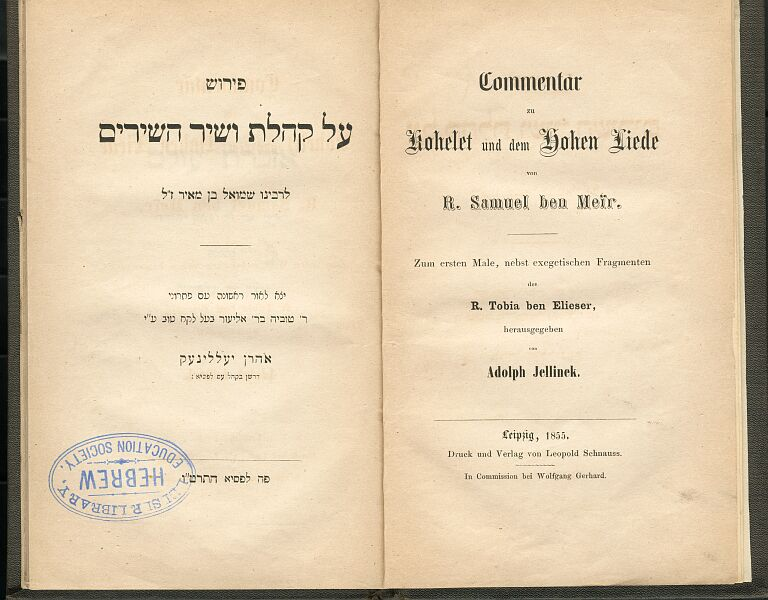

The Song of Songs in Medieval Northern France - Peshat Exegesis Against its Historical and Cultural Background

Among the interesting features of the history of the Song of Song’s Jewish interpretation are two, probably related phenomena: a) the emergence and flourish of Peshat exegesis which focused on the literal interpretation of the Song of Songs; b) a relatively great number of medieval “Ashkenazi” commentaries, the authors of which are either anonymous or conjectural.

Three such commentaries are Rashbam’s commentary on the Song of Songs (published by A. Jellinek in 1855), which provides a unique perspective on the Peshat school of exegesis at its climax, and two more little-known anonymous commentaries of the same provenance: a commentary published by A. H|bsch in 1866 and attributed by some scholars to Joseph Kara, and a commentary published H. J. Mathews in 1896, belonging to the same northern-France provenance of the 12th-13th centuries. These two works share a unique characteristic: they have given up the allegorical interpretation of the Song of Songs and are dedicated exclusively to the literal meaning of the work: an expression of human love.

This bold deviation from the accepted traditional stand toward the Song of Songs which - on the face of the matter - is similar to modern critical philological/historical understanding of the Song of Songs, is differently motivated and expresses a unique track of the Jewish/Christian polemic.

Sara Japhet

David Kimhi - Between Philology and Exegesis

In accord with Kimhi tradition, Radak began his writing career around 1205 with a monumental work on biblical Hebrew language, the first part of which is a grammar, Sefer Mikhlol, the second a dictionary, Sefer ha-Shorashim. Our Provengal exegete went on to write commentaries on Chronicles, Psalms, Proverbs, Former Prophets, Latter Prophets and Genesis. Inspired by the great twelfth century Andalusian philosopher, Maimonides, Radak also composed separate esoteric philosophical commentaries on the account of creation' (maaseh bereshit; Gen 2:7-5:1) and account of the Chariot' (maaseh merkavah; Ezekiel 1). Although Radak wrote no separate polemical work, he addresses (and aims to refute) christological readings throughout his writings, often drawing upon Joseph Kimhi’s Sefer ha-Berit, a literary record of a disputation between a Christian and Jew.

Featured here is a passage from CJS RAR MS 375, a late thirteenth-early fourteenth century manuscript of the Shorashim, which is perhaps Radak’s most influential work. It quickly became standard in Jewish learning and even achieved popularity among Christian Hebraists well into the seventeenth century. (It was used, for example, by the translators of the 1611 King James Bible.) In the post-script to the Shorashim, Radak mentions that his two-part linguistic work was produced at the request of biblical scholars in Provence who found it difficult to understand “the books of the authors who came before [which were] translated from one language to another and are difficult to understand.” This would seem to be a reference to the great Hebrew linguist, Jonah ibn Janah, whose grammar-dictionary combination (Kitab al-Luma` and Kitab al-Usul, written in Arabic) is indeed the model of Radak’s work. Although Ibn Janah’s magnum opus was indeed translated into Hebrew in twelfth century Provence by Judah ibn Tibbon, evidently there was a need for a clearer Hebrew work of this type, which Radak aimed to fill.

A glimpse of Radak’s daily life emerges in another note in the post-script to the Shorashim, where the author apologizes to the reader for any errors that might have crept into his grammatical-linguistic work and attributes them to the fact that “all the days that I worked on [the Mikhlol and Shorashim], most of my time was spent on my [primary] work teaching young men Talmud.” This remark helps to explain the extensive citations of Talmud and Midrash in Radak’s commentaries, a feature unusual in the peshat school our Provengal exegete inherited and would have seen, for example, in the commentaries of Abraham ibn Ezra (1089-1164), the eminent Andalusian imigri exegete who represents the “pure” hermeneutics of that tradition. Although Radak did indeed take ibn Ezra to be his peshat mentor, this Provengal Talmud teacher was also at home in rabbinic exegesis and evidently was moved by its creativity, depth and inspirational force. Manifesting a special talent for integration, Radak harnessed the two exegetical streams that converged in twelfth century Provence to biblical commentaries that combine linguistic acuity and historical sensitivity with interpretive creativity, imagination and religious passion. All of these qualities contribute to the lasting impact of his work to this day, especially among readers of Scripture who seek a historical-philological interpretation that does not forfeit the spiritual dimension of Holy Writ.

Mordechai Cohen

Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Polemics in Spain

In his Responsa as in his other writings, Ibn Adret often deals with exegetical questions, thereby referring to the inner-Jewish debate about allegorization, an exegetical technique he was opposing to. Moreover, Ibn Adret shows his familiarity with the arguments of contemporary Christian polemicists against Judaism, e.g. the Dominican friar Raymond Martini (Ramsn Martm) and the Franciscan Raymond Lull (Ramsn Llull), both of whom were arguing about specific questions of how to understand the Hebrew Bible and the Talmud.

A polemical treatise authored by Ibn Adret and called Ma’amar ‘al Yishma’el (“Treatise against the Muslim”) responds to the 11th-century Muslim scholar Ibn Hazm of Cordoba. Having written the fullest Bible criticism of any Muslim scholar, Ibn Hazm had claimed that the Hebrew Bible cannot be identical with the original text revealed to Moses on Mount Sinai but must be a later corruption. A closer look at Ibn Adret’s response to Ibn Hazn shows that the Rabbi, when refuting classical Muslim literature, was also aiming against contemporary Christian exegesis, since he saw certain commonalities between Islamic Bible criticism and the Christian claim that the Jews had abandoned the religion of the “Old Testament” and replaced it by the Talmud.

Martin Jacobs

Printed & Glossed Bible

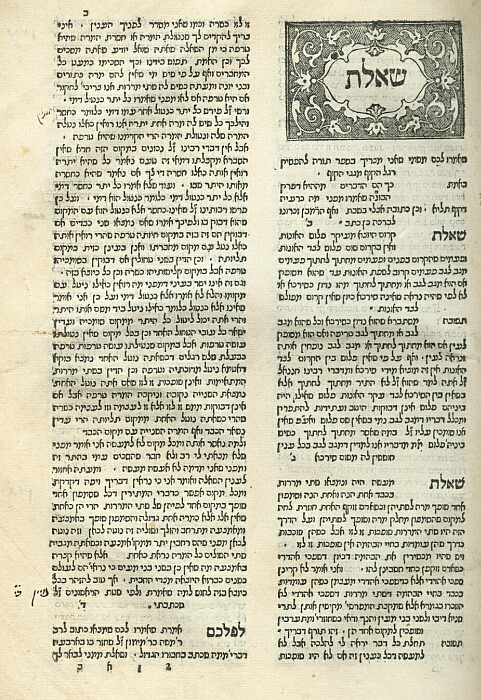

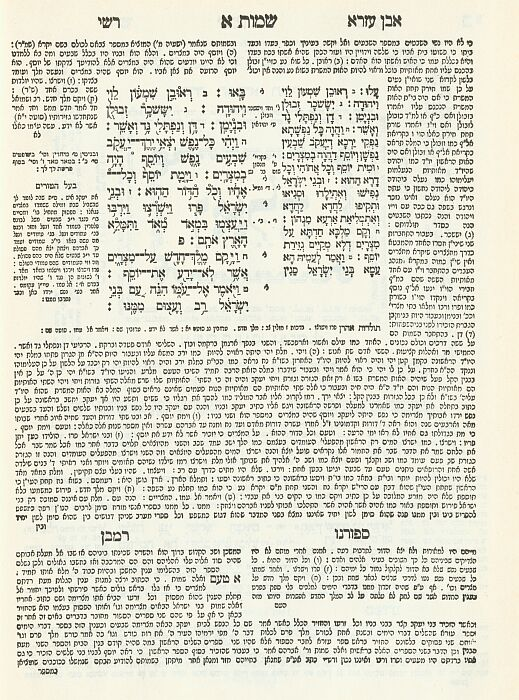

Miqra’ot Gedolot - the Format is the Function

The Miqra’ot Gedolot format, with a large-type Biblical text accompanied by a translation and surrounded by commentaries, is half a millennium old. It is most common with texts from the Pentateuch but has been used for all the books of the Bible. The edition pictured here, originally printed in Warsaw from 1860 through 1869, is a particularly comprehensive one. It was reprinted in the middle decades of the 20th century in the United States. It includes Onkelos’ Aramaic translation; the commentaries of Rashi, Ibn Ezra, Nahmanides, and Sforno; marginal Masoretic notes (Masorah Parva) and a separate, more detailed apparatus of Masoretic comments (Masorah Magna); marginal references to rabbinic literature; and Masoretic and numerological comments by Jacob b. Asher, the “Baal ha-Turim.”

A new English-language edition of the Book of Exodus is in preparation for publication, in a format that mimics the traditional Miqra’ot Gedolot. Of the four major commentators, Sforno, from Renaissance Italy, is replaced by Rashi’s grandson R. Samuel b. Meir (“Rashbam”), whose willingness to contradict traditional interpretation has at last put him “on the page” even in Miqra’ot Gedolot editions from Orthodox presses. The Aramaic translation is replaced with two English translations made under the auspices of the Jewish Publication Society, the older one more literal and the newer one more free. A digest of comments offers a glimpse at a range of commentators from Bekhor Shor (a contemporary of Rashbam) to Sforno. Explanatory notes complete the edition.

Michael Carasik

Margins and Mirrors in England

![Fig. 1: The Byble, that is to say all the Holy Scripture; in whych are co[n]tayned the Olde and New Testamente, truly & purely tra[n]slated into English, & nowe lately with greate industry & dilige[n]ce recognised.](/legacyexhibits/assets/images/AndWehaveRevealedtoYou/img_9.png)

![Fig. 2: The Byble, that is to say all the Holy Scripture; in whych are co[n]tayned the Olde and New Testamente, truly & purely tra[n]slated into English, & nowe lately with greate industry & dilige[n]ce recognised.](/legacyexhibits/assets/images/AndWehaveRevealedtoYou/img_10.png)

After the Reformation, it became increasingly common for Protestants, particularly in England, to own vernacular bibles. Some translations, following the tradition of the medieval glossed bibles, had extensive notes printed in the margins. But readers often added their own notes as well. This “Matthew” Bible from the CJS Library is a folio, the largest format for a printed book, and was published in London in 1549 by John Day. Large bibles like this were printed for liturgical use but, given later versions and the brief reassertion of Catholicism by Mary I (1553-8), such bibles migrated into private households. This is clearly the case with this bible, in which there are notes by at least five different readers from the mid-sixteenth century to the eighteenth century.

One seventeenth- or eighteenth-century reader has marked up a passage in Isaiah 44, which has the following printed note at the top of the page: “Christ promeseth to delyuer his churche, whiche he hath redeamed. Idolatry & knelyng before ymages .etc. are confuted.” Such attacks upon “idolatry” and images were a common feature of anti-Catholic polemics. But a few pages later, the same reader has written in the margins of Isaiah 51, in mirror writing, a record of an economic transaction: “Iohn Spencer dothe owe me xxs for halfe a yares wagys of the whyche xxs I haue receyved thre nobels.” Such secular notes are surprisingly frequent since bibles were secure places to “file” information. At the same time, writing paper remained expensive and scarce until the invention of wood-pulp paper in the nineteenth century and a bible was often the only book that a household owned. Bibles were consequently used not only for exegetical purposes but also for family records, household accounts, and a variety of other notes. Children’s alphabets and owners’ signatures are two of the commonest forms of writing found in bibles and are frequently found in the margins as well as on the blank pages at the beginning and end.

In this copy, one reader has practiced various letters in the margins of Revelation, while another has tried to copy the capital letter “E” and has got as far as writing “Ely” beside “Elyzabeth” in the printed text. A third reader has twice written his signature, “John Welster,” in the margins. Finally, a nineteenth-century reader has inserted a newspaper cutting at Psalm 100. It reads: “‘Many persons,’ says The Chambers Journal, ‘must have been struck with the awkward beginning of the line in the 100th Psalm: ‘For why? The Lord our God is good.’”

The truth is, popular ingenuity - represented in this case perhaps by the printer - has taken the liberty of changing the old word, ‘forwhy,’ meaning ‘because,’ which gave good sense and translated the original, but which had fallen out of common use, into the modern ‘for why?’ Surely the restoration of the word might still be attempted before it is too late.”

Peter Stallybrass

Selected Bibliography

-

Allemanno, Johanan ben Isaac. Hay ha-`olamim = L’immortale. Parte I, La retorica., edited and translated by Fabrizio Lelli (Quaderni di “Rinascimento,” No. 21). (Firenze: Leo S. Olschki, 1995)

-

Berlin, Adele (translator and editor). Biblical Poetry through Medieval Jewish Eyes. (Indiana Studies in Biblical Literature, Indiana University Press, 1991)

-

. The Cambridge History of the Bibleedited., edited by Peter. R. Ackroyd, G. W. H. Lampe and S. L. Greenslade (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1963-70)

-

Cohen, Norman J. “The London Manuscript of Midrash Pesiqta Rabbati; a Key Text-Witness Comes to Light,” in Jewish Quarterly Review (73, 3 (1983)). (Dropsie University, 1983. pp. 209-237)

-

Fishbane, Michael (editor). The Midrashic Imagination: Jewish Exegesis, Thought, and History. (State University of New York Press, 1993)

-

Fletcher, Angus John Stewart. Allegory, the Theory of a Symbolic Mode. (Cornell University Press, 1964)

-

Gelles, Benjamin J. Peshat and Derash in the Exegesis of Rashi. (Leiden: Brill, 1981)

-

Golb , Norman (editor). “Judaeo-Arabic Studies: Proceedings of the Founding Conference of the Society for Judaeo-Arabic Studies,” in Studies in Muslim-Jewish Relations (Vol. 3. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1997).

-

Goldin, Judah. Studies in Midrash and Related Literature., edited by Barry L. Eichler and Jeffrey H. Tigay (JPS Scholar of Distinction Series. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1988)

-

Greenberg, Moshe. Parshanut ha-mikra ha-yehudit. (Jerusalem: Mosad Byalik, 1992)

-

Halivni, David. Midrash, Mishnah, and Gemara: The Jewish Predilection for Justified Law. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986)

-

Jacobs, Martin. “Die Institution des j|dischen Patriarchen: eine quellen-und traditionskritische Studie zur Geschichte des Juden in der Spdtantike,” in Texte und Studien zum antiken Judentum (No 52. T|bingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1995).

-

Japhet , Sarah (editor). The Bible in the Light of its Interpreters - Ha-Mikra bi-re’i mefarshav: sefer zikaron le-Sarah Kamin. Sidrat sefarim le-heker ha-Mikra mi-yesodo shel S. Sh. Peri. (Hebrew University, 1994)

-

Jones, Ann Rosalind and Stallybrass, Peter. Renaissance Clothing and the Materials of Memory. (Cambridge Studies in Renaissance Literature and Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2000)

-

Kugel , James L. and Greer, Rowan A. Early Biblical Interpretation. (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1986)

-

Levenson, Jon D. The Hebrew Bible, The Old Testament and Historical Criticism. (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1993)

-

Madigan, Daniel A. The Qur’an’s Self Image: Writing and Authority in Islam’s Scripture. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001)

-

Schwartz, Seth. Imperialism and Jewish Society, 200 B.C.E to 640 C.E.. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001)

-

Safrai, Shmuel. The Literature of the Sages. (Assen, Netherlands: Van Gorcum; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1987)

-

Signer , Michael A. and Van Engen, John H. (editors). J_ews and Christians in Twelfth-Century Europe._ (Notre Dame Conferences in Medieval Studies, No. 10. University of Notre Dame, 2001)

-

Smalley, Beryl. Study of the Bible in the Middle Ages. (Notre Dame University Press, 1964)

-

Stern, David. Midrash and Theory: Ancient Jewish Exegesis and Contemporary Literary Studies. (Rethinking Theory. Northwestern University Press, 1996)

-

Stern, David. Parables in Midrash: Narrative and Exegesis in Rabbinic Literature. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991)

-

Strack, Hermann Leberecht and Stemberger, G|nter. Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash. (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1996)

-

Visotzky, Burton L. Reading the Book: Making the Bible a Timeless Text. (New York: Anchor Books, 1991)

Contributors

- Haggai Ben-Shammai

- Adele Berlin

- Michael Carasik

- Mordechai Cohen

- Natalie Dohrmann

- Jacob Elbaum

- Josef Gulka

- Martin Jacobs

- Sara Japhet

- Adiel Kadari

- Tamar Kadari

- Deeana Klepper

- Naomi Koltun-Fromm

- Joseph Lowry

- Dan Sheerin

- Dalit Rom-Shiloni

- Michael Signer

- Peter Stallybrass

- David Stern

Special thanks

Special thanks to Arthur Kiron for his assistance in organizing this virtual exhibition