Religious Communities in Islamic Empires

Introduction

In the seventh century CE a new monotheistic faith appeared in the Near East – Islam. The new faith was not only a spiritual movement, but also a political power which soon after its emergence changed the map of the entire Mediterranean basin, and beyond, as far as the gates of India. The most prominent Jewish communities in the early Middle Ages lived under Muslim rule. Politically and legally they were treated as a minority, as were the Christians, who in the first centuries of Islam actually constituted a numerical majority in many areas. Soon after being integrated politically into the realm of Islam most of these Jewish communities gradually integrated into the Arabic culture. Within this broad framework evolved Judeo-Arabic culture. The period between the 7th and the 11th century could be justly defined as formative for both societies – the Muslim one was actually shaped in this period, and the presence of the majority of Jewish population worldwide under Islam modified Jewish life profoundly.

It is crucial therefore to analyze the emergence of both societies during this period in order to understand their long-term relations as well as their new identities. Their shared culture was unique in the medieval context; it had no parallel anywhere in Christian Europe. In a broader historical context it may be seen as a continuation of ancient Near Eastern tradition, namely the Judeo-Aramaic and Judeo-Hellenistic cultures. Yet another important aspect of the relations between Jews and Muslims in the Middle Ages and early modern period is the “Ottoman experience”. This is the story of a mid-size Jewish community that had lived under Byzantine rule and underwent two profound changes: First it found itself under the rule of a young, assertive and vigorous Muslim empire, the Ottomans. Secondly, it was overwhelmed by an influx of immigrants and refugees from Spain, who eventually had become the dominant majority. These wide-ranging and complex sets of relationships received a fresh comparative examination in the Mediterranean-Islamic context by this year’s (2006-07) CAJS Fellows.

Haggai Ben-Shammai

Exhibit

The saga of the critical edition of Ibn Tibbon’s Hebrew translation of Saadya Gaon’s Emunot ve-De`ot

Haggai Ben-Shammai

1) Saadya Gaon, Book of Beliefs and Convictions

Saadya Gaon (882 - 942) was no doubt one of the giants of Jewish culture in the early Middle Ages. A Native of Egypt, during the period of his most important activity he lived in Baghdad, part of it as head of the Sura Yeshiva. Among his major accomplishments was the Book of Beliefs and Convictions, which is the first attempt by a prominent member of the Rabbinic establishment to present Rabbinic Judaism as a philosophical system, compatible with scientific and philosophical systems of his time. Like most works of Saadya Gaon in prose it was written in Judaeo-Arabic (entitled Kitāb al-Amānāt wa-’l-i‛tiqādāt), which made it accessible to Jewish intellectuals who were much better versed in Arabic culture than in the Jewish one. Also, Hebrew at that time did not have the necessary vocabulary that could be used for philosophical discourse. The Judaeo-Arabic text has survived in two almost complete manuscripts and numerous fragments. Two critical editions have been published by S. Landauer (1880) and J. QafiÎ (1972), the latter with a modern Hebrew translation.

2) Judah Ibn Tibbon (ca. 1120-ca. 1190)

He was the founder of a family of translators who were active in Provence. They were responsible for the translation of a considerable part of the Judaeo-Arabic classics and Arabic science into Hebrew. Born in Granada (Muslim Southern Spain), where he acquired mastering knowledge of Arabic, he emigrated to Lunel in Provence. One of his last, most mature works was the translation of Saadya’s Beliefs and Convictions (translated 1186). For more than eight centuries this work was studied by most Jewish scholars in Ibn Tibbon’s translation. Consequently the book has been preserved in many manuscripts. It was first printed in Istanbul (Constantinople, 1562), and then in numerous editions, none of them critical. This translation has gained additional importance after it had transpired that there are considerable differences between the two main manuscripts that had been the basis for the critical edition of the Arabic text (Mss Oxford and St. Petersburg), and that the Ibn Tibbon translation in most cases supported the St. Petersburg version. In spite of this fact both editors of the editions of the Arabic text preferred the Ms Oxford. Subsequent research has shown that numerous Genizah fragments as a rule support the St. Petersburg version. A critical edition of Ibn Tibbon’s translation has thus become a vital tool in establishing the text of the Arabic original, in addition to its being a scholarly desideratum in its own right for two main reasons: a) This is the text that was quite popular among Jewish readers for eight centuries who wanted to acquaint themselves with Saadya’a philosophy. b) It is one of a quite large number of texts that constituted the core of the canon of Jewish culture for centuries that as yet have not appeared in critical editions.

3) Henry Malter (1867-1925)

A native of Galicia, He pursued his higher education and his Jewish modern scholarly training in Germany, where he received his Ph.D. (Heidelberg 1894) and rabbinical diploma (Berlin Hochschule 1898). In 1900 he was appointed professor of medieval philosophy and Arabic at the Hebrew Union College, Cincinnati; later he moved to Dropsie College where he taught until his demise. Beginning in Germany, and later in America he was one of the most prolific scholars in Jewish studies at the time. The gem of his oeuvre was Saadia Gaon; His Life and Works, Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1921 (reprinted several times), which has remained the classic work on the subject. On p. 372 of this book Malter wrote in the course of his discussion of Ibn Tibbon’s translation: “A critical edition based on all the existing MSS, and on a careful comparison of the Arabic recensions, including the Genizah fragments, has been prepared by the present writer and will be published soon after the present work”. With Malter’s early demise the promised edition disappeared.

4) The discovery of Malter’s lost work

Since I came first to CAJS as a Fellow during the 1994-95 academic year, I have tried to find traces of Malter’s edition which he promised in his book. Rumors had it at the time that it was somewhere in the basement of CAJS. All my inquiries during later years (when I returned in 2002 and 2007) with various members of the staff had not brought any results. In the spring of 2007 Dr. Arthur Kiron, the Curator of Penn’s Judaica collections, offered to help me find some uncataloged documents written by Solomon Skoss (a scholar of Judeo-Arabic who was one of the most prominent faculty of Dropsie College) that are kept in the archives of CAJS library. We went down to the archives for an extended period of time and searched through many documents but were unable to locate the particular Skoss writings we were looking for. But we did find two cardboard boxes with stickers on them saying “Malter Saadia”. On opening the boxes we found that they contained the lost draft of Malter’s critical edition of Saadya Gaon’s Emunot ve-De`ot and more.

5) The Contents of the Malter Boxes

-

Text of Judah Ibn Tibbon’s translation of Saadya Gaon’s Emunot ve-De`ot: 312 pages (in cardboard files) in Malter’s hand, accompanied by two apparati: a) Variant readings from MSS and early printed editions, referred to in the texts by Arabic numerals; b) Comparisons with the Judaeo-Arabic original, referred to in the text by Hebrew letters. There are additional references within the text in the form Arabic numerals in parentheses, but the actual part of these footnotes has not been found so far. The first file contains a brief undated document composed by the late Prof. Israel Efros. The document records the contents of the files, the structure of the edition and the siglae of the MSS. Preliminary checks have shown that the information contained in this document needs some corrections.

-

Several hundred pages of an English translation of Maimonides’ Guide of the Perplexed, in Malter’s hand. Given extant translations in print this work may be relevant for scholars who are especially interested in comparing various translations of the Guide.

-

A notebook containing a Hebrew translation of the part 1 of Qirqisani’s al-Anwar, in Malter’s hand. Prof. J. Blau in Jerusalem is working on a Hebrew translation of the entire work, and may be therefore interested in the text of this translation.

Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire

Yaron Ben-Naeh

The Ottoman city, its markets, its coffeehouses and streets have been the arena for the daily encounter of Muslims, Jews and Christians, natives and foreigners. The close contact between ethnic groups, and especially that of Jews and Muslims, had a significant role in their acculturation. Ottoman Jews, and Ottoman Jewish society in the early modern period were greatly influenced by Ottoman culture in its broadest sense. The various manifestations of this acculturation are a main theme evidenced in a wide range of sources, such as congregational institutions, via material culture at the domestic sphere as in the synagogue, to folklore, social norms and mentality.

Ms. Philadelphia, Halper 68

Sagit Butbul

This manuscript contains a biblical glossary to I Kings in Judaeo-Arabic. This is but one of a group of glossaries, rather old, from the period before 1000 CE, in which the transliteration system is phonetic. J. Blau and S. Hopkins subsumed the spelling in these texts under the name “early phonetic Judaeo-Arabic spelling” (EPJAS). Biblical glossaries are lists of selected biblical words – usually, though by no means always, rare or difficult biblical words – and their renderings into Judaeo-Arabic. Sometimes writers of glossaries give not one meaning of a given word, but two and sometimes more; e.g. the biblical בירח (I Kings 6:37) in this glossary is translated as בשהר, בלהילל. We can see from this example several characteristics of early Judaeo-Arabic glossaries: the phonetic spelling (בשהר instead of the standardized JA spelling: באלשהר; בלהילל and not באלהלאל), the fact that a seemingly simple word (for speakers of modern Hebrew, at least) is given in this glossary, and that it receives not one, but two possible translations.

In a recent article (“On Aramaic Vocabulary in Early Judaeo-Arabic Texts written in Phonetic Spelling”, JSAI 32 (2006), 433-471) J. Blau and S. Hopkins treat three biblical glossaries of eastern origin. One of these glossaries is this very glossary to I Kings. Some of the words which appear in these glossaries can attest to their eastern, namely Babylonian origin: Aramaic words from the spoken Aramaic vernacular, which are not attested in the Judaeo-Aramaic of the Talmud and Geonic literature, but are to be found in non-Jewish Eastern dialects, as Syriac and Mandaic; for example, the translation וככילונאת to the biblical ובלולים (I Kings 6:8; see Blau and Hopkins, p. 464.).

Time, Myth and the History of Halakhah in the Late Gaonic Period

Yossi David

Our picture of the intellectual world of the tenth century Babylonian academies is far from being complete. However, due to the large quantity of Halakhic writings and their ambivalence approach toward non-legal aspects of the Talmud we tend to describe the Gaonic world as anti-mythic. Focusing on counter examples of such estimation offers a refreshing view on the Gaonic mythical consciousness and attitude toward Aggadic narratives. It is possible to trace back the apocalyptic theme mentioned in R. Sherira Gaon’s famous epistle and the meaning and uses of this theme in the construction of historical picture of the Halakhah. Exposed there are the theological connections of Gaonic world with early gnostic and apocalyptical traditions on the one hand and Islamic theological principles on the other. R. Sherira Gaon and his son R. Haya did elevate Adam’s figure to be the Father also draws their theological effort to reconstruct an entirely new concept of patriarchy.

Hebrew Panegyric, Jewish Court Culture, and the Articulation of Legitimacy

Jonathan Decter

Hebrew poems in praise of men (panegyrics) were exchanged among Jewish intellectuals in the Islamic world from Iraq to al-Andalus and arguably constituted the most prevalent of medieval Hebrew secular genres. Scholars have dismissed panegyrics as unpalatable sycophancy anathema to modern literary tastes, which has resulted in the neglect of a rich source for studying the power structures of medieval Jewish societies and the ways in which political legitimacy was articulated and promulgated. Hebrew panegyrics are literary portraits that present constructions of Jewish power that were intimately bound to images of power in the contemporary Islamic milieu. Like the Arabic panegyrics offered to Caliphs and Muslim governors, Hebrew panegyrics praise addressees for their far-reaching reputations, their ability to render fair judgment, their noble lineage, their eloquence, their promotion of Jewish practice, and their efforts to thwart religious heretics. Panegyrics were not only shared among Jewish intellectuals belonging to a specific social network but also created a “virtual court culture” through the ritual exchange of texts over distances.

Mediterranean Jewish Merchants and the Conquests of the Normans

Jessica Goldberg

Letters among merchants make up one of the largest categories of documentary materials in the Cairo Geniza. Over 100 years of research by generations of scholars has shown that most letters come from groups of inter-connected merchants. Since some of these merchants wrote dozens of extant letters, and at least one received several hundred of them, many of these merchants’ names and lives are now known in a wealth of detail hitherto unprecedented for any “average” medieval person. Thanks to merchants’ descriptions of their activities, their goods, and their troubles, as well as their off-hand references to familial, communal, and political events, we have a unique window into the day-to-day workings of both the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean economies of the central Middle Ages.

Two documents in the Halper collection, Halper 389 and Halper 414, together form the longest extant mercantile letter in the Cairo Geniza. (Halper 414 is the small inserted second page, folded into the very long sheet that forms, as in most letters, both the writing surface and the wrapper of the letter). Not simply long, this letter, written around 1063 by the North African merchant Salama ibn Musa (Moses) the Sfaxi (from the town of Sfax), is one of the richest letters on political and military events. As he attempts to explain to his unhappy partner in Cairo why he has failed to do almost any productive business in the past year, Salama places the blame variously on movements and attacks by the Norman fleet against Sicily, small-scale warfare between the Sultan of North Africa and one of his wayward governors, payments to Bedouins for access to the olive groves of S. Tunisia, the difficulties of evading customs officers, and the machinations of jealous fellow merchants all over the central Mediterranean. Salama’s losses are our wealth: no letter in which business went well would ever tell us as much about how merchants tried to make a living.

The Talkhīs of Yusuf b. Nuh and Abu al-Faraj Harun

Miriam Goldstein

By the tenth century of the common era, the Jewish community of the Middle East and Mediterranean was a cosmopolitan group: Arabic-speaking, although well-versed in Hebrew and Aramaic, and steeped in the latest developments in theology, philosophy, medicine and astronomy, as rendered in Arabic by the scholars of the Arabic-speaking world. In order to effectively address such an audience, the exegete had to address these areas of knowledge and the assumptions that accompanied them. The Bible exegesis written in Arabic by Karaites and Rabbanites alike in the tenth and eleventh centuries exhibits this wide variety of subject matter, and reflects particularly strikingly the theological assumptions of the Jewish communities of the area, with their Mu’tazilite bent.

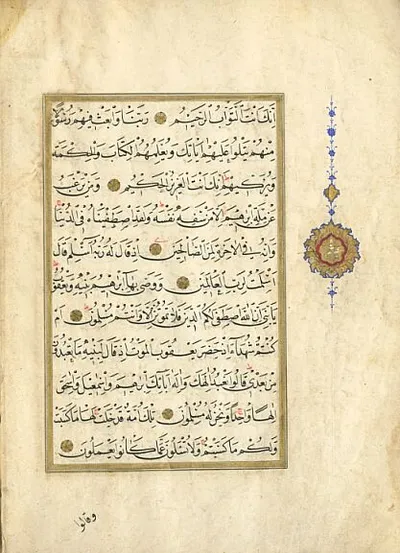

This page is from the Talkhīs of the 10th century Karaites Yusuf b. Nuh and Abu al-Faraj Harun, both of whom were key figures in the formation of the Karaite house of study in Jerusalem, a thriving center of scholarship in the Jewish world during the tenth and eleventh centuries. The page is one version of their commentary on the story of the Tower of Babel, and reflects the exegetes’ assumption of contemporary theological tenets regarding divine justice, as well as their familiarity with discussions of languages and their speakers in the Muslim world. This composition is preserved in at least seven different manuscripts in the collections of the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg, Russia. The page on display contains folios 39b-40a from MS Russian National Library Yevr.-Arab. I:4785, a 310 page manuscript written in a thirteenth-century semicursive Hebrew script.

Judah ben Elijah Hadassi Ha-‛Avel

Daniel Lasker

His major opus, Sefer Eshkol Ha-Kofer (“The Cluster of Henna,” cf. Canticles 1:14), the title page of which is pictured here, was published first in Eupatoria (Gözleve), 1836, with Caleb Afendopolo’s précis, Naḥal Eshkol (“The Stream of the Cluster”), which was composed in 1497. This book, written in 1148-1149, has a most peculiar style: 379 alphabets, starting alternately from beginning to end then end to beginning (alef to tav and tav to alef), and every stanza ends with the Hebrew letter khaf sofit (kha). The syntax and style make deciphering the book very difficult, but it is possible to understand the book with much effort. Eshkol ha-Kofer serves as a summa of Karaite Judaism as it had developed from the proto-Karaite Anan ben David to Hadassi himself. Both his legal determinations and his religious opinions seem to have their roots in his Karaite predecessors: Anan, Benjamin al-Nahawendi, Daniel al-Qūmisī, Ya‛qub al-Qirqisānī, Yefet ben Eli, Yūsuf al-Baṣīr (Joseph ha-Ro’eh), Yeshu‛a ben Judah, and others. It is no surprise, therefore, that most of Hadassi’s philosophical views are based on Islamic Kalām.

Hadassi’s most notable innovation was his recording of ten principles of Judaism. Hadassi was one of the first Jews, Rabbanite or Karaite, to formulate a systematic and detailed list of dogmas, preceding, thereby, Maimonides. There is nothing particular new or surprising in the contents of his listed; Hadassi admits that he, himself, had taken the principles (ishurim in his terminology) from his predecessors. Nonetheless, the manner in which he arranged them was a novelty in Jewish thought. These principles are: 1) Existence of a Creator; 2) the Creator’s eternity and unity; 3) creation of the world; 4) the ministry of Moses and the other prophets; 5) the truth of the Torah; 6) the obligation to know Hebrew; 7) the Temple is the residence of God’s glory and in-dwelling; 8) resurrection of the dead; 9) accountability; and 10) reward and punishment.

Hadassi’s importance is as a transitional figure, who was the last representative of the classical Karaism of the Land of Israel Mourners, and the first representative of new Byzantine forms of the religion. Hence, although Hadassi was in the main still loyal to the traditional Karaite Kalāmic philosophy, written among Muslims mainly in Judaeo-Arabic, he did adumbrate the newly emerging Byzantine school of late medieval Karaite philosophy, of which the first known full adherent was Aaron ben Joseph, writing 150 years after Hadassi.

Ancient Persian status-symbols adopted by the Arabs after the Conquest

Milka Levy-Rubin

The conquest of the East by the Arabs, was followed by the adoption of many practices and customs of the conquered societies. Among these were Persian Royal manners and status symbols which were used in order to distinguish between the different classes in Persian society. Persian society was a rigid caste society going back to very ancient times. Status symbols included special dress items such as special head-gear, foot-gear, expensive robes made of special fabrics and decorated with embroidered edges, bejeweled belts and swords, and horses and their paraphernalia including saddles, reins, and other horse ornaments. All of these were privileges of the upper classes only. The lower classes were required to dress with humility.

Having gone through a period of acculturation, the Muslims adopted this concept of a class society and applied it to the new society which they were forging. In this new society, the Muslims represented the privileged upper class, with its codes of dress and behavior, while the non-Muslims were required to adopt the part of the restricted lower class and dress and behave with humility. This is clearly perceived in the legal document articulating the social status of the dhimmis or non-Muslims, shurut ‛Umar written in the eighth century. The dress prohibitions made on the non-Muslims in the shurut reflect dress customs of the Persian society, while the manners and customs demanded of them are actually part of the code of behavior in the presence of the king or other high officials in the royal court or outside it.

The attached drawing found in the Scroll of Esther in the collection of the Center for Advanced Judaic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, portrays Mordecai, who was accorded the special privilege of wearing a royal robe previously worn by the king, riding on a horse which had been ridden by the king, and paraded in the city square, led by Haman who proclaimed before him: “This is what is done for the man whom the king desires to honour” (Esther, 6:11). This ancient Persian royal custom, going back to very ancient times, was adopted by the Muslims. Upon their appointement, Muslims officials were given a prestigious horse and expensive robes, and their appointment was proclaimed when their horse was paraded in public. Non-Muslims were forbidden among other things, to use saddles or iron stirrups, and in many cases to ride horses altogether, as these were a clear symbol of nobility and therefore reserved for Muslims only.

Following in the Footsteps of Rav Ḥai Gaon’s Lost Dictionary

Aharon Maman

Rav Ḥai Gaon’s dictionary, Kitāb al-Ḥāwi, composed in the late 10th or early 11th century, was unfortunately lost by the end of the thirteenth century, and only small vestiges have survived in the Cairo Genizah. It was the only one in the history of Hebrew and Aramaic lexicography to be organized anagrammatically. Up to 1890 it was only known through old quotations in Jewish works, then when some twenty leaves were discovered in the St. Peterburg’s Genizah collections. A. E. Harkavy published a sample of one leaf. In 1976 S. Abramson published another two leaves. More Genizah material was discovered in Cambridge both in the Taylor-Schechter and the Westminster College collections, and one leaf at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. Recently I published a critical edition of ten leaves (see “The Remnants of R. Ḥai Gaon’s Dictionary Kitāb al-Ḥāwi in the Adler and Taylor-Schechter Geniza Collections”, Tarbiz 69 (2000), pp. 341-421 [in Hebrew]; preceded by “Ḥai Gaon’s Method in his Lexicon Kitāb al-Ḥāwi,” Studies in Ancient and Modern Hebrew in Honour of M. Z. Kaddari (ed. S. Sharvit), Ramat-Gan 1999, pp. 235-249 [in Hebrew]).

From the cultural and social point of view this work reveals some striking features. Rav Ḥai Gaon quotes al-Khalil ibn Aḥmad’s Kitāb al-‛Ayn, the first dictionary ever composed by an Arab lexicographer (eighth century) and uses it for a better understanding of vague biblical words. Rav Ḥai’s openness to non-Jewish sources is also seen in his readiness to learn from the Christian tradition of the Catholicos of Baghdad to the understanding of a Psalm. This was a tenth century example of an open interfaith scientific dialogue.

Maimonides and the Dogma of Creation

Charles Manekin

In this autograph copy of Maimonides’ Commentary on the Mishnah (Oxford, Bodleian Ms. Pococke 295) there are many marginal corrections and additions added by the great rabbi. One of these has to do with the fourth of Maimonides famous “thirteen principles of Torah,” the principle of divine priority. In the early version Maimonides did not include the dogma of creation; later he mentioned the dogma and its significance in the margin of his copy, thus raising the question whether there are other significant differences in his thought between his earlier and later writings.

Two Ersatz “Persian” Miniature Paintings

Vera Moreen

Among the holdings of the Abraham J. Karp collection (Box 4, Item 9a-c) at CAJS are manuscript leaves containing miniature paintings in the Persian style. They are palimpsests as they are painted over (and thus conceal) parts of the texts with which they have no connection.

The first leaf is from an Arabic manuscript on ritual purity, a Kitāb al-ŧahārat (‛Book of [Ritual] Purity’), probably a section from one of the larger, popular Muslim legal codes. The text is copied in excellent script on blue paper, which is often of “eastern,” even Russian provenance. The miniature painting shows an amorous “picnic” with four figures arranged in two groups, two seated and two standing young men on a floral field against a beige background, with a bowl of fruits separating the groups. It is likely a homoerotic scene with three older men “courting” a younger man, a celebrated literary theme often depicted in Persian miniature paintings.

The second piece is a single leaf from a Persian manuscript from a popular collectionof tales about biblical and qur’anic prophets, involving here Daniel and Idrīs (Enoch), copied in excellent script on typical undyed oriental paper Its miniature is a highly animated scene of a polo match—the pastime par excellence of Persia and a common visual cliché of the Persianate tradition—depicting two horsemen who are chase the ball over a floral field, set against a light green background.

These miniatures are by the same, not wholly inexpert artist, and depict highly conventional (from the point of view of the tradition of Persian miniature paintings) scenes. They date no earlier than the late 19th century and, quite possibly, from the 20th century. Such fakes were and continue to be available on the market, especially in Israel, for the tourist trade.

Joseph ibn Nahmias and The Light of the World

Robert Morrison

Joseph ibn Nahmias’ (fl. 1400 CE) The Light of the World is the only known text on theoretical astronomy to be written by a Jew in any variety of Arabic. The Light of the World is the only known attempt to improve on the astronomy of the Muslim al-Bitruji (fl. 1200 CE). Al-Bitruji’s astronomy itself was a representative of a rare tradition in which the planets’ motions occurred on the surface of the celestial sphere, with the earth at the very center, and not in the plane of the zodiac. Ibn Nahmias was also trying to solve scientific problems posed by Maimonides’ Guide for the Perplexed.

Although Joseph Ibn Nahmias comes from a well-known family, little is known about his life. His roots were in either Toledo, Aragon, or Castille. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, we have reports of his text turning up, probably via the Hebrew translation, in the Veneto.

”The Great Eagle”

Sarah Stroumsa

“The Great Eagle”, an honorific often attached to the name of Moses Maimonides, underlines his regal position in the Jewish community. At the same time, the image of the wide-spread wings does justice to the breadth of his intellectual horizons. The circumstances of his life—exile, travels, and a forced conversion to Islam—gave Maimonides opportunities to encounter a particularly variegated list of political systems, cultural trends and systems of thoughts. His extraordinary personality and his insatiable intellectual curiosity drove him to make full use of these opportunities, integrating the various influences into his literary output.

Maimonides’ “Eight Chapters” are a short treatise on ethics, written as an Introduction to his Judeo-Arabic Commentary on tractate Avot . Its purpose was, as he said, to serve as “a key to our following commentary.” In the Preface to this treatise Maimonides forcefully formulates the guiding principle of his intellectual drive: “Harken to the truth, whoever may have said it.” Porta Mosis is a selection of Maimonides’ topical Introductions to Mishnaic tractates. Published in 1655 by Edward Pocock, this publication served indeed as a key and a gateway, opening the way to the philological, non-theological study of Judaism and Islam. In this, it represents another link in the relay-race of transmitting knowledge, whoever may have said it.

Jewish Conversion to Islam in Persia

Daniel Tsadik

The image you see is a copy from a lithograph of a Persian text called “Iqamat al-Shuhud fi Radd al-Yahud fi Manqul al-Rida’i (Erection of Evidence in Refuting the Jews as Transmitted by al-Rida’i),” written by Muhammad Rida’i Jadid al-Islam in early 19th century Iran. The author was, according to his own testimony, an important Jewish cleric in Tehran, the capital city. He converted to Islam and wrote this extenstive anti-Jewish text so as to show the supermacy of Islam from various texts, including Jewish ones (Hebrew Bible and others).

Jewish Inclusion in Algerian and Tunisian Networks in the 16th-18th Centuries

Yaron Tsur

Algeria and Tunisia in the 16th-18th centuries were a lively meeting ground for Muslim and Jewish populations. Adding to the autochthonous layer of Arabs and Berbers were two new Muslim elements: Ottomans and Moriscos - Muslim Spanish exiles. The Jewish population was enlarged, first by Jewish Spanish exiles, then by immigrants from the Western Sephardi diaspora who constituted the local Leghorn branch (Livornese). Current research has barely touched on the integration of different religious groups into common economic or social networks. This is the topic of the proposed study: to characterize, on the basis of historical sources, the various networks that included Jews, to define their boundaries, and to analyze the significance of the intra-Jewish and inter-religious cooperation that comes to light.

One key source for the study is Algeria’s Responsa literature from the 16th-18th centuries. This includes an important, unpublished manuscript from the early Ottoman period, by Rabbi Abraham Ibn-Tawaah.

Selected Bibliography

• Abū al-Fatḥ ibn Abī al-Ḥasan, al-Sāmirī. The continuatio of the Samaritan chronicle of Abū L-Fatḥ Al-Sāmirī Al-Danafī, translated and annotated by Milka Levy-Rubin. (Princeton N.J.: Darwin Press, 2002).

• Allony, Neḥemya. Ha-sifriyah ha-yehudit bi-yeme ha-benayim: reshimot sefarim mi-Genizat Ḳahir ba-ʻarikhat Miryam Frenḳel, Ḥagai Ben-Shamai uve-hishtatfut Mosheh Soḳolov. (Jerusalem: Makhon Ben-Zvi le-ḥeḳer Ḳehilot Yiśraʾel ba-mizraḥ, 2006).

• Bābā’ī ibn Farhād. Iranian Jewry during the Afghan invasion: The Kitāb-i Sar Guzasht-i Kāshān of Bābā’ī b. Farhād, text edition and commentary by Vera Basch Moreen. (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1990).

• Ben-Naeh, Yaron. Yehudim be-mamlekhet ha-Sulṭanim: ha-Ḥevrah ha-Yehudit ba-Imperyah ha-ʻOt’manit ba-meʾah ha-shevaʻ ʻeśreh. (Yerushalayim: Hotsaʾat sefarim ʻa.sh. Y.L. Magnes, ha-Universiṭah ha-ʻIvrit, 2006 or 2007).

• Ben-Shammai, Haggai and Benjamin Hary, eds. Esoteric and exoteric aspects in Judeo-Arabic culture. (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2006).

• Ben-Shammai, Haggai and Joshua Prawer, eds. The history of Jerusalem: the early Muslim period, 638-1099. (Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi; New York: New York University Press, 1996).

• Cohen, Mark R. and Udovitch, A. L., eds. Jews among Arabs: contacts and boundaries. (Princeton, N.J.: Darwin Press, 1989).

• Cohen, Mark R. Jewish self-government in medieval Egypt: the origins of the office of head of the Jews, ca. 1065-1126. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1980).

• Cohen, Mark R. Jews in the Mamlūk environment: the crisis of 1442 (a Geniza study). (London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 1984).

• Cohen, Mark R. Poverty and charity in the Jewish community of medieval Egypt. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2005).

• Cohen, Mark R. The voice of the poor in the Middle Ages: an anthology of documents from the Cairo Geniza. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2005).

• Cohen, Mark R. Under crescent and cross: the Jews in the Middle Ages. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1994).

• Crescas, Ḥasdai. Sefer Biṭul ʻiḳre ha-Notsrim / Ḥasdai Ḳreśḳaś; be-targumo shel Yosef Ben Shem Ṭov; hehedir Daniyel Y. Lasḳer. (Ramat-Gan: Universiṭat Bar-Ilan ; Be’er-Shevaʻ: Hotsa’at ha-sefarim shel Universiṭat Ben-Guryon ba-Negev, 1990).

• Elias, Jamal J. The throne carrier of God: the life and thought of ʻAlā’ ad- Dawla as-Simnānī. (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995).

• Frank, Daniel H., Oliver Leaman, and Charles H. Manekin. The Jewish philosophy reader. (London; New York: Routledge, 2000).

• Freudenthal, Gad, ed. Studies on Gersonides: a fourteenth-century Jewish philosopher-scientist. (Leiden; New York: E.J. Brill, 1992).

• Freudenthal, Gad, Jean-Pierre Rothschild and Gilbert Dahan, eds. Torah et science: perspectives historiques et théoriques: mélanges offerts à Charles Touati. (Sterling, Va.: Peeters, 2001).

• Freudenthal, Gad, Jean-Pierre Rothschild and Gilbert Dahan, eds. Aristotle’s theory of material substance: heat and pneuma, form and soul. (Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press, 1995).

• Freudenthal, Gad, Samuel Kottek and Paul B. Fenton, eds. Mélanges d’histoire de la médecine hébraïque: Études choisies de la Revue d’histoire de la médecine hébraïque (1948-1984). (Leiden; Boston, MA: Brill, 2003).

• Freudenthal, Gad. Science in the medieval Hebrew and Arabic traditions. (Aldershot, Hampshire, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2005).

• Grinboim, Abraham and Alfred L. Ivry (ed.). Hagut u-maʻaśeh: sefer zikaron le-Shimʻon Ravidovits bi-melot ʻeśrim ṿe-ḥamesh shanim le-moto. (Tel-Aviv: Ts’eriḳover motsiʾim la-or ʻavur Universiṭat Ḥefah, ha-Faḳulṭah le-madaʻe ha-ruaḥ, 1983).

• Ben-Shammai, Haggai, ed. Ḥiḳre ʻEver ṿa-ʻArav: mugashim li-Yehoshuʻa Blaʼu ʻal yede ḥaveraṿ bi-melot lo shivʻim. (Tel-Aviv: Universiṭat Tel Aviv, 1993).

• Hollenberg, David. Interpretation after the End of Days: the fāṭimid-ismā’īlī ta’wīl (interpretation) of Ja’far ibn manṣur al-yaman (d. ca. 960). (Ph.D. Diss.: University of Pennsylvania, 2006).

• Ibn Janāḥ, Abū al-Walīd Marwān. Sefer ha-haśagah: hu kitab al-mastalḥaḳ le-R. Yonah ibn G’anaḥ be-tirgumo ha-ʻivri shel ʻOvadyah ha-Sefaradi, edited by Daṿid Ṭene; hishlim ṿe-ʻarakh Aharon Maman. (Yerushalayim: ha-Aḳademyah la-lashon ha-ʻIvrit, 2006).

• Levi ben Gershom. The logic of Gersonides: a translation of Sefer ha-Heqqesh ha-yashar (The Book of the correct syllogism) of Rabbi Levi ben Gershom. (Dordrecht; Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1992).

Contributors

-

Yaron Ben-Naeh - Hebrew University/CAJS 2007

-

Haggai Ben-Shammai - Hebrew University/CAJS 2007

-

Sagit Butbul - Hebrew University/CAJS 2007

-

Yossi David - Hebrew University/CAJS 2007

-

Jonathan Decter - Brandeis University/CAJS 2007

-

Jessica Goldberg - University of Pennsylvania/CAJS 2007

-

Miriam Goldstein - Hebrew University/CAJS 2007

-

Daniel Lasker - Ben-Gurion University/CAJS 2007

-

Milka Levy-Rubin - Hebrew University/CAJS 2007

-

Aharon Maman - Hebrew University/CAJS 2007

-

Charles Manekin - University of Maryland/CAJS 2007

-

Vera Moreen - CAJS 2007

-

Robert Morrison - Whitman College/CAJS 2007

-

Sarah Stroumsa - Hebrew University/CAJS 2007

-

Daniel Tsadik - Tel Aviv University/CAJS 2007

-

Yaron Tsur - Tel Aviv University/CAJS 2007

Special Thanks

Special thanks to David McKnight and his digitization team at SCETI and to Leslie Vallhonrat in the Van Pelt Systems department for their amazing efforts in bringing the exhibit to completion and launching it on the web; and to Arthur Kiron, Penn Library Curator of Judaica Collections for his assistance in organizing this virtual exhibit.