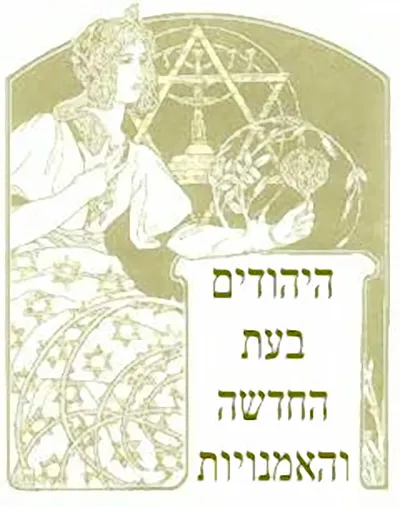

Modern Jewry and the Arts

Introduction

This year’s exhibition on Modern Jewry and the Arts presents work in a rich diversity of cultural media and genres. Jewish artists have been respected contributors to modern music, film, theater, and visual art, and their activities encompass high art, mass media, and popular culture forms. But what is “Jewish Art?” Any art produced by Jews? Any art with Jewish content? Is there a distinctive Jewish style?

Most of these questions presume standards set by conventional cultural histories, which despite universalizing goals, define the arts in national terms. Does that mean, then, that Jewish art is exclusively made in Israel, the modern Jewish state, or does it also describe art made by Jews in the Diaspora? Clearly, the questions that emerge from this study of Jewish art and culture are bound to the most pressing concerns of modern Jewish history generally, as well as to questions concerning the production and valuation of modern art.

For a study of Jewish art and culture, diversity acquires additional significance, beyond the variety of forms and media. These works express a diverse “Jewish-ness” — belying the homogeneity that the term “modern Jewry” implies. They testify to the diversity among Jews, the many ways of being a modern Jew, and through the arts, suggest ways of constructing a modern Jewish identity. At the same time, while often preoccupied with the concerns of Jewish community, Jewish artists in the modern period have avoided parochialism and participated in the many national cultures of which they are also a part. This participation extends to culture’s institutional forms: its markets and commerce, its museums and academies, media distributions and technology-all sites where Jews have played an active and formative role.

Our exhibit offers a few examples of works that address these issues and our discussions this year. Each Fellow has selected an image from a particular branch of the arts that represents the strength and the challenge of modern Jewish culture. They demonstrate the extraordinary depth and variety of Jewish art, and suggest, we hope, new avenues of cultural research.

Carol Zemel

Exhibit

Art

Maurycy Gottlieb, Self-Portrait, 1878

Ezra Mendelsohn

In this beautiful painting Maurycy Gottlieb presents himself to us in the formal attire favored by Central European intellectuals of his time. But he also seems to be accentuating his “Jewish features ” - his rather thick lips, half-closed, melancholy eyes, and large nose. He therefore presents to the world his twin identity as “European, ” even “Pole ” ( “Maurycy, ” or, as he was known in the German-speaking lands, “Moritz ”) and as Jew ( “Moshe, ” or “Moyshe ”). The co-existence within Gottlieb’s soul of these two identities provides a key to the understanding of the life and work of this pioneer “Jewish artist. “

Ken Aptekar, Her Father Dragged Her from Shtetl to Shtetl [with a sewing machine]

Carol Zemel

Ken Aptekar’s paintings deal with ethnic and gender stereotypes. This image, Her Father Dragged Her from Shtetl to Shtetl [with a sewing machine.](1996), uses Francois Boucher’s Portrait of Mme. Pompadour (1756) as its source, and delivers witty and moving insight on the modern Jewish woman. The text portion, etched in glass that covers the painted surface, is long and detailed; reading it carefully demands that the viewer’s attention crawl over every detail of painted ribbon, frill and furbelow. Mme Pompadour, and Rococo style of painting have long been considered the essence of _frou-frou_femininity in our culture, but it is a femininity of wealth and aristocracy, of leisure play and frill, of gentle curves and erotic theater. And while it seems so remote from shtetl story of Mierle Pomerance (not Pompadour), schlepping her sewing machine from town to town as she “fashioned clothes for Jews, ” the sense of fashion, fate and fantasy draws the two women close. “‘A couturihre your grandma could’ve been,’ my mother says, ” in the syntax of translated Yiddish. The story ends with the artist’s greater sense of possibility— “I escaped when I became an artist ” -but leaves the Jewish woman sewing for the far-off Jewish princess, whose cultural standard is set -still- by the Pompadour.

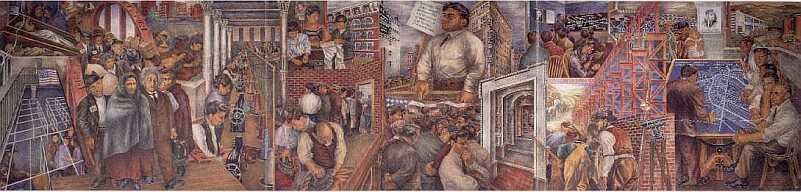

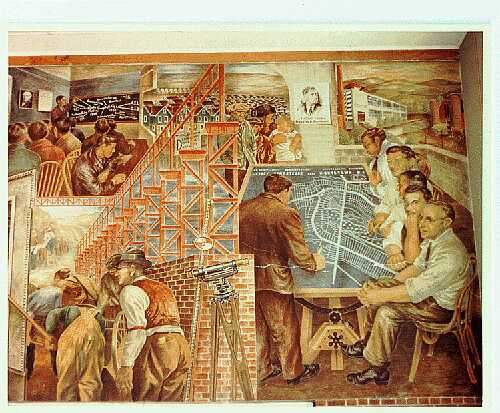

Ben Shahn, Mural for the Jersey Homesteads, 1936-37 Roosevelt Public School, Roosevelt, New Jersey

Dianna Linden

In 1936, Ben Shahn (1898-1969) was selected to create a mural for the Jersey Homesteads, a Jewish workers’ utopian community in New Jersey. This was the first mural that Shahn completed under the New Deal, and he painted it in true fresco which he mastered as an apprentice to Diego Rivera. Inspired by Rivera, by Italian Renaissance frescoes, modernist montage and avant-garde film (Shahn was friends with film theorist Jay Leyda), Shahn created a multi-level fresco sub-divided into individual vignettes, and marked by quick thematic and temporal shifts. Divided into three main sections, the untitled fresco represents Jewish immigration to America, the oppressive tenements and sweatshops of New York, and the reforms demanded by labor unions and those provided by the New Deal. Rather than a path specific to Jews, Shahn proposes a direction for the whole working class to follow. Namely, to build cross-union and inter-cultural alliances, to move back to the land, and live by the example of the Jersey Homesteads.

Music

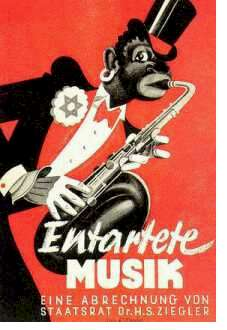

”ENTARTETE MUSIK” - Degenerate Music

Marion Kant

After Hitler seized power in January 1933 the Nazis immediately installed racial laws and expelled political enemies and generally unwanted people from German society. They made a more or less normal life impossible for those, whom they labelled “degenerate”, “unhealthy” or “sick”. By the end of the 1930s the Nazis had begun to gas helpless inmates of insane asylums, the educationally sub-normal and the physically crippled. 75,000 German citizens died in the so-called “Action T4” and another 400, 000 were forcibly sterilized. The gassing of these innocent and harmless people stopped in 1941 because the Nazi regime needed the experienced gassing teams to set up the death camps at Treblinka, Belzec, Sobibor and Maidanek.

Behind the aggressive Darwinian culling of what the Nazi called the hereditarily unfit lay a deep cultural pessimism. Three generations of prophets of doom like Spengler had foretold den Untergang des Abendlandes or the Decline of the West. The preachers of disaster had taught them that Western and in particular German civilisation and culture were in decline and one of the agents of that decline was what the Germans called untranslatably Das Judentum or Jewry. The Jews represented the faceless modern world, the loss of community, and urban development. They became the scapegoats for everything from slums to female emancipation, a deeply threatening aspect of modern life. This cultural anti-Semitism was a new variant of an old paranoia, but it was on a different scale. Judaism was no longer rejected as a religion, with all its awful implications. It was turned into a race. Cultural pessimism and social Darwinism reinforced each other. Jews were parasites, as Hitler was fond of explaining and in nature healthy organisms exterminated parasitic life forms. In the social world, healthy humanity, that is, the Aryan race, had to cull the parasitic Jewish one. The Jews had to be stripped of civil rights, isolated and removed from humanity. Hitler declared that he wanted the Jews eradicated and an entire nation worked towards that goal.

The ideological mechanisms produced one-dimensional explanations. Thus, for the Nazis, artists fell under the category of “Jewish” as soon as they did not submit to the prescribed cultural policies. Modernity was Jewish, consequently modern composers had to be Jewish. Jazz was Jewish, hence jazz musicians per se were Jewish. For some artists this was an honorary title: the writer Erich Maria Remarque, who wrote the famous All Quiet on the Western Front asked for his novels to be included, when the books were burnt in Berlin in May 1933. He wished to be a member rather of “Jewish society, ” not a German one, which had made such murderous distinctions. The exhibitions of “Entartete Kunst ” staged in June 1937 and on “Entartete Musik ” that followed in May 1938 were public displays of such thinking. The Nazis saw them as powerful ideological instruments and, therefore, intrinsically political, in service to the racial state.

The Nazis took art and music seriously: deadly seriously. They saw them as powerful ideological instruments and, therefore, intrinsically political, in service to the racial state. Because the Nazis politicised the arts, some artists and critics have reacted since 1945 by claiming that the arts must be apolitical. Is that an acceptable response to the barbarous misuse of artistic activity? This is an important question, which every artist has to answer in her or his own way. It is an illusion to imagine that we can escape the realities of a highly political world by ignoring the close relationship of politics and arts. The arts are not now above politics any more than they were in the 1930s.

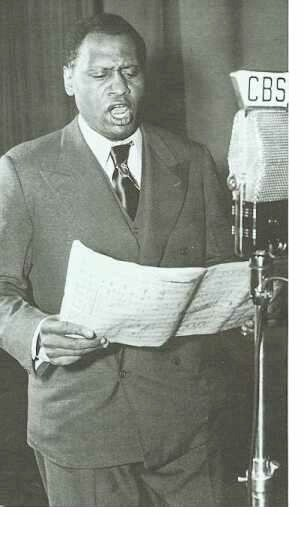

Paul Robeson’s “Chassidic Chant of Levi Isaac of Berditschev”

Jonathan Karp

Robeson’s concert repertoire was always eclectic, reflecting not just his linguistic virtuosity but also the Left’s ideological commitment to internationalism and “the songs of many lands ” (he also performed Chin Chin, the Chinese marching song, an Eskimo ballad, a Gaelic folksong, the Volga Boat Song, and Loch Lomand, as well as numerous operatic pieces in different languages and a large number of spirituals). Nevertheless, as early as the 1920s, Robeson professed the belief that the cultural and musical affinities between blacks and Jews are qualitatively unique and transcendent ones.

Zahava Ben sings Arabic, Israel, 1995

Amy Horowitz

In early 1995, Zahava Ben released a CD on her own label, entitled Zahava Ben sings Arabic. The silver and gold cover portrays Ben inscribed within the profile of the renowned Egyptian singer, Umm Kulthum. Later, in the fall of 1995, in the aftermath of Prime Minister Rabin’s assassination, Moroccan Israeli singer, Zahava Ben released a CD of Umm Kulthum repertoire on the Helicon label. As many Israelis and Palestinians embraced a shared experience of grief over Rabin’s death and the unsettling peace prospects, Zahava Ben’s CDs and appearances in Nablus and Jericho resonated with musical, political, and commercial overtones.

Contemporary Jewish Music in America 1960s-1990s

Mark Kligman

The growth of Jewish music over the past few decades has been staggering. While it is impossible to provide an exact number of recordings, since no distributors or retail outlets service the entire Jewish community, members of the industry estimate that there are currently over 2,000 recordings of Jewish music available and close to 250 records released each year. There are over four hundred artists and groups performing Jewish music today and most listeners and consumers are aware of only a few. The creation of new Jewish music, which ranges greatly in terms of musical styles, is found throughout the Jewish community: religious communities, Orthodox, Conservative, Reform and Renewal; Yiddishists, Yiddish songs and klezmer music; Israeli; and, art music composers and established popular artists. Jewish music has arrived and is a growing industry.

Shlomo Carlebach was an important transitory figure in the world of American Jewish Music. He was born in Germany, his father was a rabbi, and trained in a yeshiva. While serving as a rabbi in New Jersey in the 1950s he began to write music. His songs combine aspects of hassidic music and folk music. Like hassidic music Carlebach songs are in two or three parts with each part repeating. Carlebach songs are “folk” music in that the melodies are accessible and easy to sing. He sang songs in various Jewish and non-Jewish contexts seeking to engage young Jews into their tradition. Music was his vechicle. One of his earliest recordings Shlomo Carlebach at the Village Gate provides an example of his well-known songs based on a verse from psalms, “Eso Einai.”

An American born baby boomer generation sought to experience Judaism and adapt their American journey. Avraham Fried is a Lubavitcher Hasid living in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn. His music is popular in the community. His songs are in Hebrew, Yiddish and English that are Hassidic in origin or original. One popular song is “Didoh Bei” which is based on a passage from the Talmud Nedarim 41a, “If you have knowledge”, the song was written by Yossi Green. “Didoh Bei” is commonly heard at Orthodox weddings. The musical style combines pop music and Middle Eastern rhythms and styles.

Debbie Friedman grew up feeling that liturgy in the synagogue was not accessible. She sought to make liturgy prayerful and participatory. She began writing music for youth services in the 1970s and as a song leader she created participatory services at summer camps. For two and half decades her music has become widely known throughout American Reform and Conservative synagogues. Some of her most popular liturgical melodies are “Oseh Shalom” and “Mi Shebeirach.” Her English songs provide new insights to biblical passages such as “Miriam’s Song” and “L’chi Lach.” The song “L’chi Lach” is an interpretation of the biblical passage Lech Lecha, Abraham’s call to go out.

American born musicians who played traditional music started the Klezmer Revival of the 1970s, they sought to discover the music of their heritage. The 78 rpm recordings of the 1920s and 1930s served as models for repertoire and style, the recordings of legendary clarinetist Dave Tarras and Naftule Brandwein. At first the klezmer revivalists reproduced the earlier recordings then they sought to innovate and adapt. Three renditions of “Der Heyser Bulgar” [“The Hot Bulgar”] trace this line of development: Brandwein’s 1920s recording, the Klezmer Conservatory Band with Itzhak Perlman, and by the fusion klezmer band The Klezmatics, who instead of full band instrumentation only use percussion with more ornamentation. The birth of new music among secular Yiddishists is growing, one example is The Well, new Yiddish songs based on poetry with the songs written and sung by Chava Alberstein with the Klezmatics, “Zayt Gezunt” [“Farewell”]).

Theater & Film

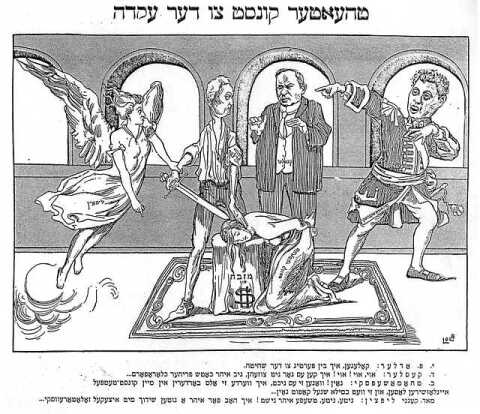

”Teater kunst tsu der akeyde”

Nina Warnke

The cartoon “Teater kunst tsu der akeyde ” (The Attempt to Sacrifice Theater Art) by Lola (pseudonym of the painter Leon Israel, 1887-1955) was published on 2 September 1910 in the Yiddish satirical magazine Der groyser kundes. It is a trenchant critique of the Yiddish theater managers who after having supported literary plays for years had recently produced a series of very popular sentimental melodramas. To critics invested in creating a literary theater this amounted to an unforgivable betrayal of the ideal of “art."

"Le-an nelech hashavu’ah?” (“Where shall we go to this week?”)

Anat Helman

A caricature from a late 1930s periodical reflects the popularity of movie going amongst different sectors in Mandated Tel-Aviv. The couple on the left is dressed as typical elegant bourgeoisies; the next couple can be either Kibbutz members visiting the urban cultural center or a couple of urban workers (“poalim”), expressing their socialist-pioneering ideology through their simple clothing; the policeman represents municipal authority — although in the early 1930s the autonomous Jewish municipal police force of Tel-Aviv was dispersed and combined into the general British police force; and the tiny boy indicates that in Tel-Aviv, like in many other countries at that time, children were eager movie consumers, worrying parents and educators as to potential corrupting effects.

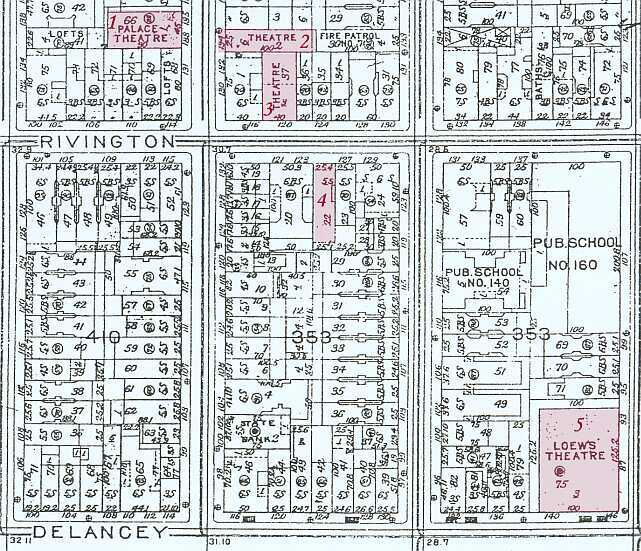

Bromley Atlas. Borough of Manhattan

Judith Thissen

The growth in popularity of the moving pictures began with the nickelodeon around 1905-1906. These small storefront theaters offered a half hour program of moving pictures and illustrated songs for five cents (hence their name). The shows ran continuously from morning to evening. People went day after day, and from one theater to another. “The moving pictures have totally revolutionized the Jewish district. It is heaven and earth and moving pictures,” reported the Forverts (Jewish Daily Forward) in May 1908. The nickelodeon boom provided immigrant Jews and their children with unparalleled access to popular entertainment and profoundly changed their recreational patterns. Their enthusiasm for the cinema is exemplified by the fact that the Lower East Side had the highest density of nickelodeons in New York City.

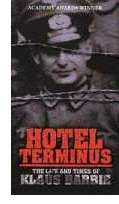

Marcel Ophuls’ Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie

Susan Rubin Suleiman

In his 1988 Academy Award-winning documentary, Hotel Terminus, Marcel Ophuls (famous for his earlier film about France under German occupation, The Sorrow and the Pity) explores brilliantly the moral and historical issues raised by the Barbie trial, and extends at the same time the art of documentary film. The image here, a black and white photograph taken around 1970, is the opening image of the film: it shows Barbie and two friends celebrating at a New Year’s party in Peru. Barbie is the man in the middle, wearing a party hat, with a drink in one hand and an upraised cane in the other. On his right, with his arm around Barbie’s neck, is Johannes Schneider-Merck, a young man at the time, who was defrauded soon afterward of a huge sum by Barbie and his pals in a currency speculation scheme. Schneider-Merck, noticeably older than he appears in the photo, is the first person whose memories of Barbie we hear in the film. By opening his documentary with a still photograph taken decades after Barbie’s crimes in Lyon and more than a decade before his trial and the making of this film, Ophuls emphasizes the passage of time and the huge distance that exists between the historical subject of the film (the Nazi criminal Barbie) and those who remember him or try to follow his tracks forty years later. Ophuls’ film presents “the life and times of Klaus Barbie” not as a linear story, but as a complicated collage of many people’s memories of the man and the times.

(For a detailed commentary on this film, see Susan Rubin Suleiman, “History, Memory, and Moral Judgment in Documentary Film: On Marcel Ophuls’ Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie,” forthcoming in the journal Critical Inquiry in 2001 or 2002).

Dance

Joseph Lewitan and the Nazification of Dance in Germany

Marion Kant

Joseph Lewitan was there when German modern dance became the one modern art, which the Nazis welcomed. Unlike literature, art or music, German Modern Dance was not declared “degenerate” but was celebrated as a truly German art form. Lewitan was one of the most important dance critics in Germany of his day, and he provides a way into that fascinating story about dance, nationalism and modernity.

In October 1927 the first issue of “Der Tanz, Monatsschrift für Tanzkultur - “Dance, A monthly Journal for Dance Culture” - Lewitan’s magazine - was published, the first serious dance journal in Germany. Lewitan’s project began at a time when the dance world was locked in a bitter dispute. The core issue of this fierce confrontation was about ‘modernity’ and ‘anti-modernity’, about adequate artistic representation, about ‘contemporary-ness’ and embodiment of the present time. The battle of the dance types reflected the ideological, political and economical divisions in Germany from the beginning of the 20th century.

Soon after the rise of Nazism Lewitan lost all his positions, which he had held in the dance world. In July 1933, “Der Tanz” announced that it was undergoing fundamental changes and a general reorganisation - Lewitan was replaced as editor and his magazine finally ‘aryanised’.

Lewitan had entered Germany from Soviet-Russia in 1920 as a Russian and he left Germany as a ‘stateless’ Jew sometime between December 1937 and July 1938. He emigrated to Paris, fled from the German Wehrmacht just before they marched down the Champs-Élysées in June 1940 to the South of France and reached Casablanca in May 1942.

In dance history Lewitan has been identified as both: the “destructive Jew” who undermined German values by being part of modernity and the “conservative” Jew who could not accept or grasp modernity in an artistic form. He at the same time became a symbol of modernity as a destructive force and its opposite, a representation of anti-modernity as a destructive force. No attempts in history or theory have been made so far to resolve this terrible contradiction, this death sentence.

Institutions & Display

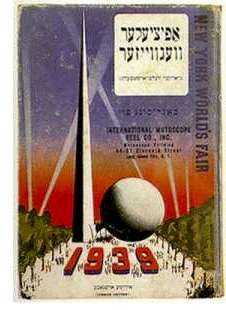

OFITSYELER VEGVAYZER NOYYORKER VELT-OYSSHTELUNG (Yiddish guide to the New York World’s Fair, 1939/40)

Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett

Zionism was by no means the only basis for the Jewish presence at world’s fairs. By the 1930s, however, the Zionist movement had succeeded in becoming the “official” national and international Jewish presence at the fair, nowhere more clearly than in the case of the Jewish Palestine Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, 1939/40. Described in much greater detail in the Yiddish guide to the Fair than in the English guide, the Jewish Palestine Pavilion exploited the slippage between the world itself and the world of the fair to perform de facto statehood. The design of the Palestine Pavilion and its contents was in accord with Meyer W. Weisgal’s desires, which he recalled years later as “something authentically Palestinian” to show that “in 1938 Jewish Palestine was a reality; its towns, villages, schools, hospitals and cultural institutions had risen in a land that until our coming had been derelict and waste… I wanted a miniature Palestine in Flushing Meadows.” Insisting—with no trace of irony—that the pavilion should steer clear of politics, Weisgal applied himself to the “construction of the Jewish State under the shadow of the Trylon and Perisphere, or, as the Jews were fond of calling it, the Lulav and Esrog.”1

Selected Bibliography

• Kalman P. Bland. The Artless Jew: Medieval and Modern Affirmations and Denials of the Visual. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).

• Richard I. Cohen. Self-Image Through Objects: Toward a Social History of Jewish Art Collecting and Jewish Museums. In The Uses of Tradition: Jewish Continuity in the Modern Era, edited by Jack Wertheimer, pp. 203–242. (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1992).

• Richard I. Cohen. Jewish Icons: Art and Society in Modern Europe. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998).

• Ezra Mendelsohn, Richard I. Cohen (editors). Art and Its Uses: The Visual Image and Modern Jewish Society. In Studies in Contemporary Jewry, 6. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

• Gideon Ofrat. One Hundred Years of Art in Israel. Translated by Peretz Kidron. (Boulder: Westview Press, 1998).

• Larry Silver. Jewish Identity in Art and History: Maurycy Gottlieb as Early Jewish Artist. In Jewish Identity in Modern Art History, edited by Catherine M. Soussloff, pp. 87–113. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

• Meyer W. Weisgal. Meyer Weisgal, … So Far: An Autobiography. (New York: Random House, 1971).

• Robert S. Wistrich. The Demonization of the Other in the Visual Arts. In Demonizing the Other: Antisemitism, Racism and Xenophobia, edited by Robert S. Wistrich, Studies in Antisemitism, vol. 4, pp. 44–72. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

• Lilian Karina, Marion Kant. Tanz unterm Hakenkreuz: eine Dokumentation. (Berlin: Henschel Verlag, 1999).

• Susan Rubin Suleiman. History, Memory, and Moral Judgment in Documentary Film: On Marcel Ophuls’ Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie. In Critical Inquiry. (Forthcoming, 2001 or 2002).

• Judith Thissen. Jewish Immigrant Audiences in New York City, 1905-1914. In American Movie Audiences: From the Turn of the Century to the Early Sound Era, edited by Melvyn Stokes and Richard Maltby, pp. 15–28. (London: BFI Publishing, 1999).

• Amy Horowitz. Israeli Mediterranean Music: Cultural Boundaries and Disputed Territories. (University of Pennsylvania, 1994).

• Ezra Mendelsohn (editor). Modern Jews and Their Musical Agendas. In Studies in Contemporary Jewry, 9. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

• Mark Slobin. Tenement Songs: The Popular Music of the Jewish Immigrants. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982).

• Mendel Kohansky. The Hebrew Theatre, its First Fifty Years. (New York: Ktav, 1969).

• Emanuel Levy. The Habima, Israel’s National Theater, 1917-1977: A Study of Cultural Nationalism. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979).

• Nahma Sandrow. Vagabond Stars: A World History of Yiddish Theater. (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1996).

Contributors

-

Anat Helman - Hebrew University/CAJS 2001

-

Amy Horowitz - American University/CAJS 2001

-

Marion Kant (ENTARTETE MUSIK | Joseph Lewitan) - University of Surrey/CAJS 2001

-

Jonathan Karp - SUNY Binghamton/CAJS 2001

-

Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett - New York University/CAJS 2001

-

Mark Kligman - Hebrew Union College/CAJS 2001

-

Dianna Linden - University of Wisconsin/CAJS 2001

-

Ezra Mendelsohn - Hebrew University/CAJS 2001

-

Susan Rubin Suleiman - Harvard University/CAJS 2001

-

Judith Thissen - Utrecht University/CAJS 2001

-

Nina Warnke - University of Texas, Austin/CAJS 2001

-

Carol Zemel - York University/CAJS 2001

Footnotes

-

Meyer W. Weisgal, Meyer Weisgal, … So Far: An Autobiography (New York: Random House, 1971), pp. 150, 158, 161 ↩