Jews beyond Reason

Introduction

This year’s research group at the Katz Center focused on the experiential, the sensual, as well as philosophical and theological reflections that occur within and beyond the rational dimension of human life. Though rooted in neurological and physical responses, our scholars showed how emotions like love, anger, anxiety, joy, fear, empathy, sympathy, sadness, desire, pain, and pleasure are shaped by culture. Among the questions they posed are: how are we to explore and better understand emotions in Jewish cultural and political contexts? Are there distinctively Jewish aspects of universal human experiences of sensation - sight, sound, touch, or scent? What does Jewish thought have to say about the non-rational dimensions of Jewish philosophy and embodied spirituality beyond reason? Discussions of experiences of suffering, bereavement, distrust, art, architecture, photography, sexual desire, Jewish thought, ethics (musar), law (halakhah), psychoanalysis, trauma and culture, and New Age Judaism in the modern State of Israel, all form part of this year’s exhibition.

Exhibit

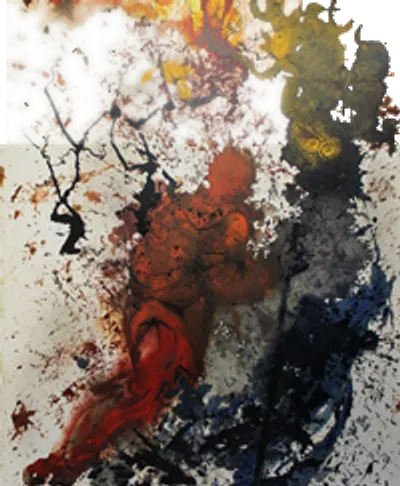

Holy Fire

James A. Diamond

The agony bled by the sermons delivered by the Warsaw Ghetto Rebbe, Rabbi Kalonymous Kalman Shapira, and collected under the title Holy Fire, coagulates as the meeting ground in an unbridgeable distance between a divine vista and a human void. They are, without a doubt, a testament to the “life” lived beyond reason that the eminent philosopher Emil Fackenheim insisted Jewish thought after the Shoah must “go to school with.” The account of the ten rabbinic martyrs, including most famously Rabbi Akiva, tortured and killed by the Romans, must forever be recounted in the shadow of the Rebbe’s challenge to God just as the deportations from the Ghetto to the death camps begin:

“In truth it is incredible that the world continues to exist despite so many screams as these. For it is said that the Ten Martyrs provoked so many screams from the angels declaring this is Torah and this is its reward? Then a voice from heaven threatened, if I hear one more sound I shall turn the world into water. Now that innocent, angelic, pure children as well as great Jewish saints, who are even greater than angels, are being killed and slaughtered only because they are Jews, are filling the entire space of the world with these screams, and the world has not reverted to water, continues to exist as if nothing has affected it?”

Neue Synagoge Berlin (1866)

John M. Efron

When inaugurated in 1866, the Neue Synagoge on the Oranienburgerstrasse in Berlin was the biggest, costliest, and easily the most conspicuous synagogue in Europe, if not the world. It was also the most spectacular example of neo-Moorish synagogue architecture. The exterior was a mixture of Islamic and Romanesque elements that deployed yellow masonry through which ran horizontal stripes of red brick. The height of the façade was 92 feet while the depth of the synagogue was 308 feet. The central entrance was flanked by two giant towers, the one on the right housing the Jewish community administration, and a library with 67,000 volumes while he tower on the left served as a Jewish museum. On the exterior, the synagogue’s showpiece was the onion dome that soared majestically some 160 feet into the air. Wrapped in a blanket of zinc and swaddled in gold ribbing, crowned with a Star of David, the great dome was the brightest and most joyful architectural feature to be found anywhere in Berlin.

With seating for 3,200 worshippers, the triple nave interior was a massive 188 feet long, 126 feet wide and soared to a height of 87 feet. The entire interior was a dazzling kaleidoscope of color, light, and texture. With Moorish decorative patterns from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the floors were inlaid with intricate mosaics, the walls were covered in richly colored stucco and then painted with stars and flora, while stalactite features hung from the ceiling and geometric and honeycomb patterns were widely deployed, including on the elaborate friezes that accented the temple’s interior. A technical breakthrough helped bathe the entire synagogue in a palette of many colors. The windows were double paned, with the outer windows made of clear glass and the inner windows of stained glass. An innovative system of gas lamps was installed in between the two panes throughout the synagogue, creating what one attendee at the synagogue’s dedication ceremony in 1866, said was a “magical effect.”

The Neue Synagoge was an immediate sensation. A contemporary newspaper account vividly described the synagogue as “a fairytale structure … . In the middle of a plain part of the city we are led into the fantastic wonder of the Alhambra, with graceful columns, sweeping arches, richly-colored Arabesques, abundant wood carvings, all with the thousandfold magic of the Moorish style.” On Friday, July 19, 1867, Lewis Carroll, author of Alice in Wonderland, visited the Neue Synagoge and recorded that “the building itself is most gorgeous, almost the whole interior surface being gilt or otherwise decorated.” Of the service itself, Carroll observed that “what was read was all in German, but there was a great deal chanted in Hebrew, to beautiful music: some of the chants have come down from very early times, perhaps as far back as David.”

No Deliverance: Abel Pann—the father of the Israeli visual Akedah

Yael S. Feldman

Abel Pann (1883-1963), the Latvian-born and Paris-trained artist who joined the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Mandate Palestine, is mostly known today for two thematic clusters of his work: the representation of Jewish persecution in Europe around WWI (horrific black-and-white scenes that one can hardly view today without anachronistically associating them with the Holocaust); and The Five Books of Moses (1923), a collection of colorfully idealized paintings of the Bible, drawn mostly with bright colors and verve, clearly evoking the exotic orient.

None of this applies however to the image of the Akedah included in this book. This lithograph clearly lacks the brightness and life that mark the rest of the images here. It also bears no resemblance to traditional Jewish representations. With its gloomy dark green and faded, almost lifeless beiges, it seems to be the first Jewish artistic attempt to focus exclusively on the human protagonists of the scene while omitting other actors – most significantly, the deliverance duo, the angel and the ram. As such, it had established the rule of “no deliverance” that has since governed the Israeli grappling with the topos as a symbol of Israel’s “national sacrifice”—its fallen soldiers.

Confronted with Isaac’s bound and limp body, viewers of this painting are compelled to sense its physical pain, almost Caravaggio-style (The Sacrifice of Isaac, 1605). At the same time, the image gives the impression of a great intimacy between the binder and the bound, echoing perhaps Rembrandt’s famous etching (Abraham’s Sacrifice, 1655). Intriguingly, it is the father’s face rather than the son’s that expresses here the horror of the moment (see the “frozen” gaze in his eyes), underlined by the sharp knife still held in his hand. Indeed, Abel Pann fashioned the scene in the name of, or from the place of the fathers of the”Isaacs” of his time (the turbulent 1920s); hence the intense ambivalence and even guilt expressed in his [self?]-portrayal. Tragically, he seems to have anticipated his own fate. By the time he was to return to this topos in the late 1940s and 50s he would be a bereaved father, one of many, of the Israeli War of Independence. His own beloved first-born Eldad fell in Gush-Etsion on the eve of Independence (1928-May 14, 1948)—an experience that naturally exacerbated the feelings of pain and guilt that have since marked his (and others’) Akedah images by Israeli artists.

The House that Joe Built

Keren Friedmen-Peleg

There are tense relations between the paper-house built by Josef Gulka, the circulation/stack manager at the Library at the Katz Center, and the objects around it. In an environment full of texts, at least some of them rare, most of them grappling with the very essence of Judaism between past and present, his small paper-house seems out of place. It has plastic lambs on top of it, a dinosaur in the front of it, and the caption “welcome” above it. The paper-house subtly interferes with the task-oriented interaction a patron might have with this library-man by provoking an unexpected smile and a question mark by its curious presence on the counter by his desk. Small enough to be ignored, yet present in a way that may justify a pause in the formal exchange with the library-man, it invites special attention and in so doing the power of the paper-house becomes clear. Serious-not-serious, formal-informal at one and the same time, Gulka’s decorative piece is a unique representation of the powerful meaning of the library in our academic life. Using symbols of sacrifice and belief, yet carrying the tenuous quality of being made from simple paper, the little house has created an interesting “flirt” between Judaism and Christianity, and between fellows and staff members. It highlights and bridges the threshold between hostility and hospitality (as Gulka himself has put it). While being exposed to multiple readings, as any other objected located in the public sphere, Gulka’s piece also has marked the common denominator between all of us: books. Yes, just accepting the invitation, “welcome,” and taking an intimate look into the inside of the little house, you immediately see: books. The power of the library, after all, has been once again expressed.

Yalkut Reuveni and the Jewish literary genre of Collectanea

Galit Hasan-Rokem

The Rare Book Room at the Library of the Herbert D. Katz Center is home to a copy of the first printed edition of the Yalḳuṭ Reʾuveni: eleh divre Kabalah mi-divre sofrim / asher yagaʻ u-matsa (translation: the Collectanea of Reuven: these are words of (mystical) tradition from writers’ words/ that he toiled and found), issued in Prague in 1660 at the printing press of the sons of Ya’akov (Jacob) Ba”k (The last name Ba”k ב”ק, an abbreviation, may refer to Bene Kedoshim, literally “sons of saints”, signifying that a forefather or -mother had suffered a violent death at the hands of non-Jews; it also may refer to an ancestor who was a Ba’al Kore, a type of cantor). The editor is Reuven ben Hoske (d. 1673; in other sources Hoeshke and Hoeshke ben Hoeshke, a form of the name Yehoshua, Joshua) Katz. Notably, the copy held at the Library of the Katz Center is interspersed with a very erudite handwritten commentary by an East European Jew by the name of Horowitz.

Yalkut Re’uveni exists in two entirely different editions. The earlier, Prague 1660 printing, also known as the “small” Y”R, is an alphabetical lexicon of various themes and items especially from Kabalistic and mystical books. The “big” Y”R, Wilmersdorf edition of l681, follows the order of the Pentateuch like the older yalkuts and it includes much more materials than the earlier edition. According to the secondary literature as well as the various book inventories and lists that I have seen, this rare printed edition is the original form of the book. There are quite a few manuscripts of the book but they are all from the eighteenth and the nineteenth century, thus most probably copies based on the printed edition or copied from other hand written copies of the first printed edition. The paleographic details given in various catalogues point to a wide distribution and interest in the book in countries spanning from North West Germany to Yemen. Today there are copies in many libraries, among them in Hamburg, Goettingen, Strasbourg and Philadelphia!

The genre of the book is a yalkut, derived from the Hebrew word to collect. According to Jacob Elbaum, one of the few scholars who have specialized in this genre, it emerged a couple of centuries after the end of the classical Rabbinic literary production of Midrash and Talmud literature. The Yalkut blossomed as a genre during two pre-modern periods: in the 13th-14th centuries CE, in works that have come to be known as the Yalkut Mekhiri and the Yalkut Shim’oni, elaborating on the books of the Bible; in the 16th-17th centuries CE, to which our specimen belongs. In the 16th century, two major collections of rabbinic literature were published by Jews in the Ottoman Empire; Ein Ya’akov and Hagadot ha-Talmud. The seventeenth century yalkut literature catered to the need to provide access to the then already voluminous libraries of Kabbalah and mysticism.

Franz Rosenzweig, Der Stern der Erlösung (1930 edition)

Miriam Jerade

Franz Rosenzweig (1886-1929) published his magnum opus The Star of Redemption (Der Stern der Erlösung) in 1921. Three years earlier, in August of 1918 while serving as a German soldier during World War I, Rosenzweig began writing down his thoughts on postcards which he mailed to his mother from the Balkan front where he was stationed. The Star of Redemptionwas driven by a critique of idealism, on the one hand, of Hegel’s philosophy of history that in Rosenzweig’s view lead to war as a collision of sovereign nation-states. On the other hand, in spite of its systematic construction, Rosenzweig critiques philosophical conceptions of rationality and rejects idealism’s absolute knowledge in light of the cry of the mortal man that opens his book. Rosenzweig’s philosophy is an engagement with individual radical singularity against a philosophy that would seek “to reintegrate the action by the same necessity into the circle of the knowable All at the moment it elaborated it” (SR, 16).

This complex system of philosophy and theology, composed during war time and embedded with notions of the Jewish liturgy and Christian theological concepts, was largely ignored when it first appeared. Gershom Scholem, the scholar of Jewish mysticism, called attention to the importance of the work when the second edition (shown here) appeared in 1930, a year after his death, but it was not until the end of the Second World War that its importance began to be appreciated. The book is divided into three parts and each part begins with an introduction. In general terms, the figure of the Star shows the relation between the Self, God and the World through the theological categories of Creation, Revelation and Redemption. For the second edition, Rosenzweig included the names of the chapter sections printed in the margin of the pages. The first printed note was “About death” and the last one “The first.”

What happens to a rationalist before he starts reasoning?

Martin Kavka

The best known images of the neo-Kantian Jewish philosopher Hermann Cohen are from a series of etchings and drawings by the German-Jewish impressionist Max Liebermann. In most of them, he looks just like one expects a rationalist to look: eyes squinted so as better to look into his own mind, and more than a little snooty. (On the other hand, this drawing by Liebermann, might make some Americans think of fried chicken).

But in 1919, shortly after Cohen’s death, his student Jacob Klatzkin wrote a small book in German about Cohen’s thought that had, as its frontispiece, a reproduction of an etching by Hermann Struck (who taught Liebermann, as well as Marc Chagall). While the original German edition did not include the Lieberman engraving, Klatzkin’s Hebrew edition, published in Berlin in 1923 did. Like Klatzkin’s book, Struck’s etching is a representation of a non-Zionist by a committed Zionist. It is a stronger intervention into Cohen’s persona, and into his rationalism, than any of Liebermann’s drawings. I remain struck by the detail around the eyes. What does Cohen see off in the distance? Why does he look so quizzical, or even apprehensive? What happens to a rationalist before he starts reasoning?

Theodor Reik, Probleme der Religionspsychologie, Teil 1. Ritual

Paul Lerner

Theodor Reik (1888-1969), today largely a forgotten figure, worked closely with Freud in early twentieth-century Vienna and made key contributions to the development of psychoanalysis in Europe and the US, helping establish the role of lay analysis and introducing literary and anthropological perspectives. After serving in World War I, Reik published the first part of his Probleme der Religionspsychologie [Problems in the Psychology of Religion] in 1919. With this text he pioneered the psychoanalytic study of religion, turning his Freudian lens onto such topics as the Kol Nidre prayer and the significance of the Shofar in Jewish ritual. Several years later Erich Fromm and Frieda Fromm-Reichmann followed up Reik’s studies with their investigations of the psychoanalysis of Shabbat and kashrut (1927) and Freud himself—who wrote an introduction to Reik’s 1919 work—completed his monumental study of Moses in 1938, just months before his death. Reik’s investigations drew on his Jewish learning and his literary background—note the Moliere quote on the frontispiece—and his works stand out for their breadth and erudition.

Dialogues of Bereavement

Lital Levy

Two powerful, wrenching documentary films, To Die in Jerusalem (dir. Hilla Medalia, 2007; produced for HBO) and One Day After Peace (dirs. Miri Laufer and Erez Laufer, 2012) feature bereaved Israeli mothers on a quest to find answers and ultimately, closure. To Die in Jerusalem follows Abigail Levy, the mother of Rachel Levy, 17, who was killed in a 2002 bombing in a Jerusalem suburb. Rachel’s killer, Ayat al-Akhras, was an 18-year-old resident of the Deheisheh refugee camp in Jerusalem. Their proximity in age and close physical resemblance provoked an international media response picturing them as “could-have-been” friends or sisters. In the film, Levy pursues a meeting with Ayat al-Akhras’s parents, seeking an explanation as well as a public repudiation of their daughter’s act. Over a period of several years, the journey takes her to an Israeli prison for Arab women, to an aborted attempt to visit the al-Akhras family in Deheisheh, and finally to a meeting held remotely over satellite television. As viewers might predict, the long-sought encounter does not provide Levy with the answers she seeks. Rather, it graphically portrays the inevitable failure of a dialogue premised on a one-sided framework of expectations and mediation. Although Levy calls the shots through much of the film, when the conversation takes unexpected turns, she finds herself floundering. Ultimately she declares the dialogue a failure and walks off the set.

By contrast, One Day After Peace depicts the powerful and transformative possibilities of a genuinely open dialogue between perpetrators and victims, through conversations that do not seek a priori confirmation of the initiator’s own beliefs. In this intensely moving film, Robi Damelin, who left her native South Africa during the apartheid era for Israel, grapples with a path forward following the death of her son David, who was shot and killed by a Palestinian sniper (Tha’ir Hammad) in the course of reserve military duty in the West Bank. Damelin becomes a leader in a joint Israeli-Palestinian organization of bereaved parents, attempts to initiate dialogue with Hammad, and returns to South Africa to conduct multiple interviews with both perpetrators and victims who took part in the Truth and Reconciliation Committee. The South African sections of the film show how the transformative power of confrontation, truth telling, and forgiveness can set a nation emerging from violent conflict on a different course. The question that lingers is whether such an approach will ever be possible or feasible for Palestinians and Israelis.

Implicitly, both films dwell on questions of motherhood and bereavement as sites of connection that may transcend conflict and difference. In both films, mothers from all sides of both conflicts embrace this notion, but the various conversations in To Die in Jerusalem ultimately subordinate these “universals” to the harsh reality of political incommensurability, whereas One Day After Peace accepts incommensurability as a starting point and works forward to from there to seek out points of connection. Both films are also explorations of the roles of revenge and forgiveness in responding to the murder of loved ones. They ask us, the viewers, to reconsider our own assumptions concerning notions of victimhood, of terror, and of forgiveness. Through them we see the contingency of the roles of perpetrator and victim in competing historical narratives; we witness how questions of state violence, terror, and resistance are leveled and refuted by different parties in a conflict. These are not easy films to watch, but they are important glimpses into the experiences of human beings in long-term violent conflicts and into the efforts of ordinary people who have undergone the most unimaginable of losses to find socially meaningful responses to their pain.

Emunah u-vitahon

Shaul Magid

R. Avraham Karleitz, known as the Hazon Ish (1878-1953) was one of the most influential rabbinic figures in the twentieth century. Born in Kosava, then in Russia and studying in yeshivot in Vilna, Karleitz immigrated to Mandate Palestine in 1933, settling in the small hamlet of Bnei Brak near Tel Aviv. Over the next twenty years he helped build Bnei Brak into one of the haredi centers of the world and remains the figurehead of the community more than half a century after his death.

Hazon Ish was known for his personal piety, his Talmudic acumen, and his legal responsum. He is less known for a small book entitled Emunah u-vitahon that he refused to publish during his life fearing it would be the cause of controversy in his community. The book is a subtle and sometimes not-so-subtle polemic against the Musar Movement that had gained traction in the haredi world mid-century and also the Brisker method of Talmud study that focuses on novella (hidush) as opposed to the more straightforward understanding on the Talmudic text.

In Emunah u-vitahon, the Hazon Ish seeks to construct the halakhic subject—the one who falls in love with the law and submits him or herself to it as an act of piety and not mere obligation. The danger of musar and the mental gymnastics of the Brisker method for Hazon Ish is that these methods of human perfection require the autonomy of the self that is always subject to the deception of the yetser ha-ra’ (for Hazon Ish, the natural desire for self-interest). The only way to avoid this self-deception is through submission to a system, the law that could obligate one to act against one’s self-interest. The law should not merely be followed but be loved such that the lover submits to it as an act of fidelity.

This critique of musar is also a critique of reason and the cultivation of love of the law achieved through consistent and intricate study of its details as an alternative to the natural inclination of love of the self. Hazon Ish saw that giving too much autonomy to the self that is endemic to musar’s belief in the possibility of self-perfection through human agency would eventually endanger the sovereignty of the law in the lives of Jews.

This frontispiece is a copy of the first edition of Emunah u-vitahon published in 1954. It has been re-published many times and a full English translation appeared as Faith and Trust translated by Yaakov Goldstein in Israel in 2008.

Reading Faces

Amos Morris-Reich

The nose is the organizing feature of the reproduced images that have been placed on this page, in a layout comprised of different kinds of media including portraits, photography, and text: the page features reproductions of ancient Egyptian portraits alongside an anthropological photograph of a Polish Jew in German-occupied Lodz, taken in late 1939 or early 1940. The images and their layout entwine science and scholarship with antisemitic and racist propaganda. Different kinds of media make different claims on reality and history.

This page is from a book on ancient Judentum (a German term that includes Judaism, Jews, and Jewry) published jointly, in Nazi Germany in 1943, by a prominent geneticist, Eugen Fischer, and a prominent scholar of ancient Judaism, Gerhard Kittel. The book’s untranslatable title, speaking of Ancient World Judentum (Das Antike Weltjudentum), suggests the immanent conspiratorial nature of the Jews; the book belongs to the same general context as the then-ongoing Nazi annihilation of European Jewry. Its purpose can be made legible by reconstructing the manipulations involved in the handling and interpretation of the images and Talmudic quotations. Studying it brings up larger, looming questions: how to read such texts? how to look at such images? Are they part of Jewish history? Can they be useful for Jewish studies, and if so for what purposes and under what assumptions or constraints?

Answering Yes and No

Paul Nahme

As the dominant genre of rabbinic writing, a published volume of “responsa” or teshuvot (lit. answers) was commonly expected of great rabbinic minds throughout the generations of Jewish diaspora life. However, the responsa written by Rabbi Yosef Dov Ber ha-Levi Soloveitchik, (1820-1892) were neither typical responses to legal and ritual (halakhic) inquiries, nor were they written in the style of previous rabbinic thinkers. The text, whose title page is depicted here, represents a grand departure in halakhic writing and inquiry.

Taking the form of the halakhic responsum as a methodological means and rather than address practical halakhic queries, Soloveitchik developed insights into and innovative ways of understanding the corpus of Talmudic and medieval commentaries. His teshuvot represent studies in the theoretical halakha, especially difficult and puzzling legal positions adopted by previous rabbis, and particularly pertaining to spheres of halakha that were of no immediate practical importance, such as Temple ritual and purity. Originally published in 1863, the Teshuvot Beit Ha-Levi marked the beginning of a new era in halakhic thinking and outlined a revolutionary model of theorizing the halakha, popularized by his son, Reb Ḥayyim of Brisk, and the descendants of the Soloveitchik rabbinic dynasty. Writing in a time of growing anxieties over whether halakhic minutiae had any relevance in a rapidly modernizing and rationalizing Jewish world, Soloveitchik’s teshuvot undertook a paradoxical response of yes and no to such a question: these teshuvot introduced a radically different mode of reasoning, beyond the historicism or empirical rationalizing about law and custom (prominent of the Western Wissenschaft des Judentums); but they also sought to validate the study of halakha for its own sake (Torah li-shema) and embodied the ethos of the Yeshivah of Volozhin, where Soloveitchik served as dean between 1854-1865.

The Ordeal of Writing Hebrew

Shira Stav

What we see here is a short letter from Uri Nissan Gnessin (1879-1913), the praised Hebrew author, great artist of prose, to his friend, the Hebrew poet and literary critic Ya’acov Fichman (1881-1958), who was then the editor of the Hebrew Journal Ha-Olam (The World). Gnessin grew up in the small town Pochep in Belorussia, but traveled a lot throughout his short life. He is responsible for some of the greatest works of modern Hebrew prose, such as Be-terem (The time before) and Etzel (Beside). Along with his close friend Yosef Haim Brenner (1881-1921), he was one of a small group of writers that invested all their material and poetic efforts in order to turn Hebrew into a modern and vivid literary language. Gnessin suffered from a severe heart disease that caused his death in 1913, in Warsaw. His death shocked and saddened the small community of Hebrew writers of the time, and his friends quickly published a memorial collection of his letters and some eulogies, Ha-Tsidah (Sideways), edited by Brenner and printed in Vilna, 1914.

In this letter to Fichman from February 1909, Gnessin, who stays in his parents’; house in Pochep, humorously tries to justify why he did not write earlier, and why he did not yet send any literary writings to be published: “Honestly, my friend, Mother’s bed is always soft to put me in a sweet sleep, and I am such a weak man, unfortunately, with such a strong drive (‘yetser’) … Fichman, Fichman! If you only knew how comfortable I am right now, and the fruit jams that awaits me there with the tea, which the children will surely lick away if I dawdle.” These”innocent,” childlike excuses reveal some of the deepest issues of his literary work: the struggles of writing, the weakness of the will and the strength of the drive, the seduction of passivity and the lure of familial relations.

Desire

Zohar Weiman-Kelman

Speaking from one woman to another, this poem sets up the desire for an encounter that the poet forecloses in advance. The first stanza speaks of an “un-expected encounter” that has not yet happened (“ere still the light it did see”). The second stanza invokes “a certainty that dreams to be, ” yet declares it “will not be able to be.” These paradoxical statements thus narrate a promise and its negation. At the same time, this archival material, the poem’s first appearance, reveals another story of poetic encounter and intertextual dialogue.

The poem was written by Hebrew poet Yocheved Bat Miriam (1901-1979) and was published on August 21st, 1930, in Moznaim, an Israeli literary journal active to this day. However, this poem is little known in its original form, for until recently it was only circulating in its 1963 version. This version was part of a collection edited by the poet, who took a vow of literary silence after her son Zuzik was killed in 1948. It was only in 2014 that a full version of her collected poetry was published, including a version of this poem almost identical to the original, save for one difference: the dedication to the Hebrew poet Rachel Bluvshteyn (1890-1931). The poem’s version with the dedication comes from Bat-Miriam’s first book, Merakhok, in 1932. Because this book was published shortly after Rachel’s death in 1931 it has been taken to be a response to her death, explaining the impossibility of the address in the poem itself.

And yet, the original version, found in the Katz library collection, reveals a poem published before Rachel’s death and not yet dedicated to her. Instead, the poem declares a desire, which is then answered in Rachel’s own poem, “Ivria,” published in the Hebrew paper Davar on November 14th 1930, and dedicated to Bat-Miriam. Bat-Miriam’s dedication to Rachel is thus already an answer, coming after Rachel’s poem, continuing a dialogue, much like the one the poem describes in the third stanza: “you call, repeat, unseen/and answering you is me.” But in this dialogue not just Rachel is implicated, but also the reader, for the Hebrew word for “call” is the same word as for “read.” Thus, instead of “waiting in vain,” the poem’s call reaches us, and our reading, kri’a, is a call in return. Here the poem’s “you” [at] and “I,” meet, against the odds, against history.

Torah-Yoga

Rachel Werczberger

Torah Yoga, the attempt to synthesize Jewish texts and Hasidic knowledge with the Hindu-based Yoga practice, is one of the Jewish hybrid mind-body techniques that have recently emerged in in North America and Israel. Along with Jewish Healing, Hebrew Shamanism, the North American Jewish Renewal Movement and several communities in Israel, Torah Yoga may be perceived as a Jewish form of New Age spirituality, or simply as New Age Judaism (NAJ).

These different NAJ phenomena share, at least to some extent, a critique of institutionalized forms of mainstream Judaism—the Orthodox and Liberal denominations—and in turn attempt to renew Jewish life by means of ritual creativity and religious eclecticism. New Age Jews approach Judaism with playfulness and ease, fusing various traditional Jewish elements, and especially Kabbalah and Hasidism with New Age practices gleaned from Far Eastern religions, indigenous cultures and the Human Potential Movement. The end product may be described as a religious bricolage—a highly hybrid, individualized, experiential and emotional form of Judaism. As such, NAJ is emblematic of the subjective turn, individualization, and processes of emotionalization, that are now taking place in Jewish life.

Selected Bibliography

-

Diamond, James. “Constructing a Jewish Philosophy of Being Toward Death,” in Jewish Philosophy for the Twenty-First Century: Personal Reflections, Edited by Aaron Hughes, Hava Tirosh-Samuelson (Leiden: Brill, 2014, 61-80).

-

. Emil L. Fackenheim : philosopher, theologian, Jew., Edited by Sharon Portnoff, James A. Diamond, and Martin D. Yaffe; with a foreword by Elie Wiesel (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2008).

-

Efron, John M German Jewry and the allure of the Sephardic. Princeton, NJ ; Woodstock, Oxfordshire : Princeton University Press, [2016].

-

Feldman, Yael S. Glory and agony : Isaac’s sacrifice and national narrative, Stanford, CA : Stanford University Press, 2010.

-

. “Deliverance Denied: Isaac’s Sacrifice in Israeli Arts and Culture: a Jewish- Christian Exchange,” in The Bible Retold, Edited by H. Leneman and B. Walfish (Sheffield: Phoenix Publishers, 2015, 85-117).

-

Friedman-Peleg, Keren. ha-Am al ha-sapah : ha-politikah shel ha-traumah be-Yisrael. Yerushalayim : Mekhon Eshkol, ha-Universitah ha-Ivrit bi-Yeurshalayim : Hotsa’at sefarim a. sh. Y.L. Magnes, ha-Universitah ha-Ivrit, April 2014.

-

Hasan-Rokem, Galit. Web of life : folklore and midrash in rabbinic literature, translated by Batya Stein Stanford, CA : Stanford University Press, 2000.

-

. Louis Ginzberg’s Legends of the Jews : ancient Jewish folk literature reconsidered., Edited by Galit Hasan-Rokem and Ithamar Gruenwald (Detroit : Wayne State University Press, [2014]).

-

Jerade, Miriam. Franz Rosenzweig. In: Lecturas levinasianas., Edited by Eshter Cohen and Silvana Rabinovich (Mexico : Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico [UNAM], Instituto de Investigaciones Filologicas, 2008, 59-69).

-

Kavka, Martin. Judaism, liberalism, and political theology., Edited by Randi Rashkover and Martin Kavka (Publisher: Bloomington, IN : Indiana University Press, [2014]).

-

Lerner, Paul Frederick. Hysterical men : war, psychiatry, and the politics of trauma in Germany, 1890-1930. (Ithaca, NY : Cornell University Press, 2003).

-

Levy, Lital. Poetic trespass : writing between Hebrew and Arabic in Israel/Palestine. (Princeton, NJ : Princeton University Press, [2014]).

-

Magid, Shaul. Hasidism incarnate : Hasidism, Christianity, and the construction of modern Judaism. (Stanford, CA : Stanford University Press, 2015).

-

Morris-Reich, Amos. Race and photography : racial photography as scientific evidence, 1876-1980. Chicago & London : The University of Chicago Press, 2016.

-

Nahme, Paul. “Law, Principle, and the Theologico-Political History of Sovereignty,” in Political Theology (14. 4 (2013), 432-479).

-

Pollin-Galay, Hannah. “Avrom Sutzkever’s art of testimony: witnessing with the poet in the wartime Soviet Union,” in Jewish Social Studies (21,2 (2016), 1-34).

-

Stav, Shira. “Nakba and Holocaust : mechanisms of comparison and denial in the Israeli literary imagination,” in Jewish Social Studies (18,3 (2012), 85-98).

-

Weiman-Kelman, Zohar. “Dream of a common “loshn” [“language”] Geveb; a Journal of Yiddish Studies ((2015), 4pp).

-

Werczberger, Rachel. “Guest editor’s introduction : New Age culture in Israel,” in Israel Studies Review (29,2 (2014), 1-16).

Contributors

-

James A. Diamond - University of Waterloo / Robert Carrady Fellowship

-

John M. Efron - University of California, Berkeley / Maurice Amado Foundation Fellowship

-

Yael S. Feldman - New York University / Maurice Amado Foundation Fellowship

-

Keren Friedmen-Peleg - School of Behavioral Sciences, The College of Management-Academic Studies / Primo Levi Fellowship

-

Galit Hasan-Rokem - The Hebrew University of Jerusalem / Ellie and Herbert D. Katz Distinguished Fellowship

-

Miriam Jerade - Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México / Ivan & Nina Ross Family Fellowship

-

Martin Kavka - Florida State University / Ruth Meltzer Fellowship

-

Paul Lerner - University of Southern California

-

Lital Levy - Princeton University / Ruth Meltzer Fellowship

-

Shaul Magid - Indiana University, Bloomington / Rose & Henry Zifkin Teaching Fellowship

-

Amos Morris-Reich - Haifa University

-

Paul Nahme - Brown University

-

Shira Stav - Ben-Gurion University of the Negev / Louis Apfelbaum and Hortense Braunstein Apfelbaum Fellowship

-

Zohar Weiman-Kelman - Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

-

Rachel Werczberger - Tel Aviv University

Special thanks

Special thanks to all of our contributors, and above all to Leslie Vallhonrat, the Penn Libraries’ peerless Web Unit manager for designing this web exhibit and for meticulously reviewing every detail. This web exhibition was made possible by the help of Bruce Nielsen and Josef Gulka at the Library at the Katz Center, as well as by Eri Mizukane at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscript and Michael Overgard and the staff at the Schoenberg Center for Text and Image (SCETI) for their time and unflagging efforts coordinating the production of digital images for this exhibit.This year’s exhibition is especially indebted to Zhiyu Zhou who has programmed the new website interface to handle a number of customized features.