Hebraica Veritas?

Introduction

Christian Hebraism was an offshoot of Renaissance humanism whose devotees—biblical scholars, theologians, lawyers, physicians, scientists, philosophers, and teachers in Latin schools—borrowed and adapted texts, literary forms, and ideas from Jewish scholarship and tradition to meet Christian cultural and religious needs. Intellectual and cultural exchange did occur between Jew and Christian during the Middle Ages, but paled by comparison with what occurred between 1450 and 1750. Encounters between cultures can be fruitful, but also very painful. Certainly Christian Hebraism had such effects both upon European Jewry, and upon western tradition.

One of the most tangible witnesses to the sudden and sustained popularity of Hebraica and Judaica among Christian writers and readers during this period are books. In addition to our discussions throughout the year and the final conference, we fellows would like to share some of the books that we found most intriguing or most useful in our research. Participating fellows have each chosen a book, written a short description of it and picked an illustration to go with it. Each of these books may be found in the library of the Center for Advanced Judaic Studies or at Van Pelt Library, the main library of the University of Pennsylvania. The understanding of Judaism held by the authors of these works is not always entirely accurate, and frequently they were involved in controversies that either baffle or infuriate contemporary readers, yet some of their work has stood the test of time. Christian Hebraism in its day mediated Jewish thought to the majority of western thinkers who could not read Hebrew and contributed to the emergence of several modern scholarly disciplines including cultural anthropology, comparative religion, and Jewish studies. This encounter with Judaism paradoxically served both to confirm traditional religious beliefs in some readers, while for others it fostered the skepticism, irreligion, and toleration normally associated with the Enlightenment. While Judaism’s claim to be one of the three pillars of Western Civilization, together with Greek and Roman culture, rests primarily on the importance of the Hebrew Bible, Christian Hebraists in early modern Europe made their contribution by enriching western thought with a healthy dose of Jewish education.

Stephen Burnett

Index by author of collection item

Lancelot Addison, 1632-1703. The present state of the Jews (more particularly relating to those in Barbary) : wherein is contained an exact account of their customs, secular and religious. London : Printed by J. C. for William Crooke … and to be sold by John Courtney, 1675.

Johanan ben Isaac Allemanno, ca. 1435-ca. 1504. Sha`ar ha-heshek. Halberstadt : [s.n.] [1860]

Isaac ben Moses Arama, ca. 1420-1494. Sefer `Akedat Yitshak. Venice: Daniel Bomberg, 1546 or 1547, printed by Corneliu Adelkind.

Siegmund Jakob Baumgarten, 1706-1757. Algemeine Welt-Historie von Anbeginn der Welt bis auf gegenwfrtige Zeit. Uebersetzung der Algemeinen Welthistorie die in Engeland durch eine Geselschaft von Gelehrten ausgefertigt worden : nebst den Anmerkungen der holldndischen Uebersetzung auch vielen Kupfern und Karten genau durchgesehen und mit hdufigen Anmerkungen. Halle : Johann Justinus Gebauer, 1744-[18—?].

Roberto Francesco Romolo Bellarmino, 1542-1621. Institutiones linguae hebraicae : ex optimo quoque auctore collectae, et ad quantam maximam fieri potuit brevitatem, perspicuitatem, atque ordinem revocatae: una cum exercitatione grammatica in Psalmum xxxiii. Antwerp : Viduam & Filios Joannis Moreti, 1616.

Biblia sacra polyglotta. Vetus testamentum multiplici lingua : nunc primo impressum; et imprimis Pentateuchus Hebraicus Greco atque Chaldaico idioma; adiuncta unicuique sua latina interpretatione. Alcala de Henares : Arnaldi Guillelmi de Brocario, 1514-1517.

Johann Buxtorf, 1564-1629. Synagoga judaica; hoc est, Schola judforum in qua nativitas, institutio, religio, vita, mors, sepulturaque ipsorum e libris eorundem. Hanau: Apud Guilielmum Antonium, 1604.

Judah ha-Levi, 12th cent. Liber Cosri : continens colloquium seu disputationem de religione, habitam ante nongentos annos, inter regem cosarreorum, & R. Isaacum Sangarum Judfum; contra philosophos prfcipuh h gentilibus, & Karraitas h Judfis Basel: Typis Georgl Deckeri, 1660.

Paul Christian Kirchner. J|disches Ceremoniel, oder, Beschreibung dererjenigen Gebrduche. N|rnberg : Verlegts Peter Conrad Monath, 1724.

Johann von Lent. Schediasma historico philologicum de Judaeorum pseudo-messiis. Herbornae : Typis & sumptibus Joh. Nicolai Andreae, 1697.

Elijah Levita, 1468 or 9-1549. Sebastian M|nster, 1489-1552. Sefer ha-Dikduk - Grammatica Hebraica Absolutissima, Eliae Leuitae Germani ; nuper per Sebastianum Munsterum iuxta Hebraismum Latinitate donata, post quam lector aliam non facile desiderabis. Basel : Johannes Froben, 1525.

John Lightfoot, 1602-1675. Horf hebraicf et talmudicf. Imprensf I. In chorographiam aliquam terrf israeliticf. II. In Evangelium s. Matthfi. Cambridge, excudebat Joannes Field, imprensis Edovardi Story, bibliopolf, 1658.

Ramsn Llull, d. 1315. Raymundus Lullus Opera. Mainz, 1721[-1742]

Martin Luther, 1483-1546. Catechesis D. Martini Lutheri minor: germanice, latine, graece, & ebraice edita studio & opera M. Johannis Claii, Hertzberg ; iterum recognita & emendata. Witebergae : Excudebant Haeredes Ioannis Cratonis, 1587.

Aldo Manuzio, 1449 or 50-1515. Desiderius Erasmus, d. 1536. Institutionum grammaticarum libri quatuor. Erasmi Roterodami opusculum de octo orationis partium constructione. Venetiis : In aedibus Aldi, et Andreae soceri, Mense Iulio. 1523.

Ramsn Martm, d. ca. 1286. Pugio Fidei, Raymundi Martini … adversus Mauros, et Iudaeos; nunc primym in lucem editus. Curb verr … Thomae Turco: subindeque … Ioannis Baptistae de Marinis … Cum observationibus Domini Iosephi de Voisin. Paris, apud Ioannem Henault, 1651.

Leone Modena, 1571-1648. Ceremonies et coustumes qui s’observent aujourd’huy parmy les juifs traduites de l’italien de Leon de Modene … : avec un suppliment touchant les sectes des Caraotes & des Samaritains de nostre temps.Edition:Troisiime edition reveuk corrigie & augmentie d’une seconde partie qui a pour titre Comparaison des ceremonies des juifs & de la discipline de l’eglise. A la Haye : Chez Adrian Moetjens, marchand libraire, 1682.

Yom Tov Lipmann Muelhausen, 14th/15th cent. [Sefer Nitsahon]. Libro yntitulado Nisahon, traduzido por David Pardo. Londres, 1697.

Santi Pagnino, 1470-1541. David Kimchi, ca. 1160-ca. 1235. Thesaurus linguae sanctae. Paris: Carolus Stephanus, 1548.

Psalterium, Hebreum, Grecum, Arabicum, & Chaldeum, cum tribus Latinus interpretationibus & glossis. Genoa: Petrus Paulus Porrus, 1516. Edited by Agostino Giustiniani, bishop of Nebbio.

Christian Knorr von Rosenroth, 1636-1689. Kabbala denudata : seu, Doctrina Hebraeorum transcendentalis et metaphysica atqve theologica opus antiquissimae philosophiae barbaricae variis speciminibus refertissimum. In qvo ante ipsam translationem libri difficillimi atque in literatura Hebraica. Sulzbaci : Typis Abrahami Lichtenthaleri; Francofurti : Prostat apud Zunnerum, 1677-1678.

Azariah ben Moses de’ Rossi, ca. 1511-ca. 1578. Me’or `enayim. Mantua: 1573-1575.

Anna Maria van Schurman, 1607-1678. Opuscula hebraea, graeca, latina, gallica: Editio secunda, auctior & emendatior. Leiden: Ex officinb Elseviriorum, 1650.

John Selden, 1584-1654. Joannis Seldeni jurisconsulti Opera omnia, tam edita quam inedita / collegit ac recensuit, vitam auctoris, praefationes, & indices adjecit, David Wilkins. Londini : Typis Guil. Bowyer, impensis J. Walthoe, 1726.

John Toland, 1670-1722. Reasons for naturalizing the Jews in Great Britain and Ireland. Yerushalayim : ha-Universitah ha-‘ivrit, ha-Hug la-historyah shel ‘am Yi4sra’el, 1963.

Voltaire, 1694-1778. La Bible enfin expliquie par plusieurs aumtniers de S. M. L. R. D. P. Londres [i.e. Genhve] , 1776.

Exhibit

Raymundus Lullus Opera

Chaim (Harvey) Hames

Ramón Llull (ca. 1232-1315) was a Catalan philosopher and mystic who developed in some 265 works, an Art, or science, which he believed conclusively proved the truth of Christianity. During his long and very active life, Llull continuously refined the Art and used it in polemic against Jews and Muslims to bring about their conversion. The Book of the Gentile, written between 1274-76 in Catalan and translated very rapidly into Latin, French and Spanish, portrays a cordial disputation between a Jew, Christian and Muslim for the edification of a Gentile utilising the framework of the Art. In the work, a large measure of tolerance is shown toward the other, and Llull reveals remarkable knowledge of contemporary Judaism and Islam. The last redaction of the framework of the Art was the Ars generalis ultima completed in 1308 along with the very popular Ars brevis. The latter is extant in a late fifteenth-century Hebrew translation, and was considered by its Jewish students as an excellent work for achieving divine revelation.

Ivo Salzinger (1669-1728), the editor of the Mainz edition wanted to portray Llull’s Art as a system of universal knowledge, and to defend Llull as an alchemist (which he was not). He amassed a large collection of manuscripts (now in the Munich Staatsbibliothek) and although he died after the first three volumes appeared, the work was continued by the new editor Philip Wolff. Only eight (I-VI, IX-X) of the ten volumes originally planned were ever published under the patronage of, first the Elector Palatine, and after his death, the Archbishop of Mainz.

Pugio Fidei, … adversus Mauros, et Iudaeos; nunc primym in lucem editus

Ora Limor

Raymundus Maritini (Ramón Martí, 1220 - 1285) was the greatest Hebraist and orientalist of the Middle Ages, and the leading representative of the Spanish Dominican school in the polemic against the Jews. His knowledge of languages and his outstanding command of Biblical and post-Biblical Jewish literature knew no equal, neither in his own time nor in the following centuries.

Raymundus studied Hebrew, Aramaic and Arabic. In his opus magnum Pugio fidei adversus Mauros and Iudaeos (Dagger of Faith against Moslems and Jews), written around 1280, he tried to prove Christianity’s truth using Jewish sources: Talmud, Midrashic literature, Jewish exegesis, Jewish philosophy and Kabbalah. He believed that these sources hide old traditions which prove the main tenets of Christianity and which should be extracted from the Jewish books “like pearls from a dunghill.” His method was to bring the Jewish section in its Hebrew or Aramaic original, followed by a Latin translation and a commentary. Raymundus’ aim was not to refute Jewish sources or to annihilate Jewish books, but to use them for Christian purposes. He looked for the sources - legends in particular - which included, so he believed, Christian truth, but also those that proved that contemporary Judaism was no longer the Biblical Judaism deserving of Christian tolerance.

The Pugio made an immense contribution to Christian Hebrew scholarship and to Christian anti-Jewish polemics. For the first time Jewish rabbinical sources were exposed to Christian eyes. Christian polemicists in the following centuries (for example, in the Tortosa Disputation of 1413-1414) based their arguments on the Pugio, making it their polemical platform. The work also brings several rabbinical sayings which were later erased from Jewish manuscripts and printed editions, and for which it serves as the only source.

Ten manuscripts of the Pugio fidei are known today. The book was printed in 1651 in Paris, and again in 1687 in Leipzig. It still awaits a critical edition.

Sefer Shaʻar ha-ḥesheḳ

Fabrizio Lelli

Johanan Allemanno was born in Italy to a French Ashkenazi family. As a philosopher, he appears to have adhered to the major concerns of the Renaissance revival of studia humanitatis. His portrayal of King Solomon as an outstanding paragon of both humanitas and speculative activism follows Humanistic literary trends. In rendering Solomon a model for the Jew aspiring to the rational and mystical knowledge of God, Allemanno emphasizes Solomon’s human qualities, his virtues as well as his vices. Allemanno reinterprets traditional Arabic and Hebrew sources using contemporary Humanistic reappraisals of classical rhetoric and biography.

This nineteenth century edition of the Sefer sha`ar ha-heshek (The Book of the Gate of Desire) contains Allemanno’s introduction to his commentary on the Song of Songs, entitled Heshek Shelomoh (Solomon’s Desire), which he had dedicated to the Humanist Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494). Pico, whom Alemanno first met in 1488, had originally turned to the Jewish scholar in search of Kabbalistic hermeneutic devices for a new interpretation of the Song of Songs. Together, they strove towards the formation of a syncretic system of rational and religious thought in an attempt to overcome ideological distinctions within intellectual milieus. Their remarkable collaboration lasted until Pico’s death in 1494.

Aldi Pii Manutii Institutionum grammaticarum libri quatuor: Erasmi Roterodami opusculum de octo orationis partium constructione: quae quoq[ue] libro continentur hanc uoluenti chartam statim se offerunt

Seth Jerchower

Aldo Manuzio’s importance is not limited to the art and development of typography. The great Venetian printer was a prolific man of letters, having authored a number of extensive tractates on classical language and literature. After having mastered both Latin and Greek printing, he went on to forge a set of Hebrew types, which initially appeared in the 1499 Hypnerotomachia Polyphili. Approximately two years later, this font would be integrated into his Alphabetum hebraicum, the first Hebrew language primer printed by a Christian for Christians. However, it was also due to Aldus’ business intrigues that the Jewish Soncino dynasty of printers was precluded from activity within the Venetian Republic (the privilege would be passed on in1516 to yet another Christian printer, Daniel Bomberg of Antwerp). The present piece is a 1523 reprint of Aldus’ Greek Grammar, accompanied by a handbook of Latin by his contemporary, Desiderius Erasmus.

Vetus testamentum multiplici lingua: nunc primo impressum; et imprimis Pentateuchus Hebraicus Greco atque Chaldaico idioma

Chanita Goodblatt

One of the great achievements of Christian Hebraic Biblical scholarship, this polyglot edition was printed in Alcala de Henares, Spain by the University of Complutum (and hence known as the Complutensian Polyglot). Its six volumes were printed between 1514 and 1517, but difficulty in obtaining papal approval delayed official publication until 1521.

The first four volumes of this Biblia Polyglotta contain the Hebrew Bible, volume 5 contains the Greek New Testament, and volume 6 contains various indices and study guides (including a Hebrew-Aramaic dictionary and a Hebrew grammar). The first page reproduced here is Genesis Chapter 1. Jerome’s Vulgate translation is in the center of the page, between the Hebrew text on the right (with roots printed in the margin) and the Greek Septuagint (with an interlinear Latin translation) on the left. The Aramaic translation is found on the bottom left of the page, with its Latin translation to the right, and its roots printed in the margin.

The second page reproduced here provides an illuminating example of how the Complutensian Polyglot was used by Christian Hebraists in Early Modern England. The bottom of this page displays verses 1-10 from Proverbs: Chapter 6, and includes the Latin text in the center, with the Hebrew text on the right and the Greek text on the left. John Donne, one of the most famous preachers of his time, discusses these verses in a sermon given in 1621 (Sermons, Volume III: pp. 231-232): “In the sixth Chapter of this booke, when Solomon had sent us to the Ant, to learne wisedome, betweene the eight verse and the ninth, he sends us to another schoole, to the Bee: Vade ad Apem & disce quomodo operationem venerabilem facit, ‘Goe to the Bee, and learne how reverend and mysterious a worke she works.’ For, though S. Hierome acknowledge, that in his time, this verse was not in the Hebrew text, yet it hath ever been in many Copies of the Septuagint, and though it be now left out in the Complutense Bible, and that which they call the Kings [Antwerp Polyglot], yet it is in that still, which they value above all, the Vatican.” What is important here is Donne’s need to establish the source and authority for his reading of the Bible in a comparison of the Hebrew, Greek and Latin textual versions. To do so, he makes use of the Complutensian [as well as the Antwerp] Polyglot to establish the original integrity and meaning of the Hebrew text, further spotlighting the problems of variant Greek and Latin translations. In this manner the Polyglot Bibles served the Protestant preacher in his study of the various biblical texts and interpretive traditions.

Psalterium, Hebreum, Grecum, Arabicum, & Chaldeum, cum tribus Latinus interpretationibus & glossis

Seth Jerchower

While the Complutensian Bible may have been the first polyglot to come off the printing press (commencing with the New Testament in 1514) it was not the first to be published. The entire enterprise was to take another three years, and the Inquisition prevented its public release until 1521.

Although more limited in textual scope, the Genoa Psalter was both printed and released in 1516, and therefore qualifies as the first published polyglot Bible. An Arabic translation of Psalms was included with the Hebrew, Latin, Greek, and Aramaic versions, and this is arguably the earliest surviving instance of Arabic movable type. The Psalter holds yet an additional “first”: at Psalm 19 verse 4 appears a curious scholium, giving a detailed account of Christopher Columbus’ voyages: the earliest printed record of the discovery of the New World. Its inclusion is attributable to equal doses of mid-millennial fervor and civic pride, as it was a Genoese captain who finally brought together “the four corners of the world.”

Sefer ha-Diḳduḳ = Grammatica Hebraica Absolvtissima…

Stephen Burnett

Elijah b. Asher ha-Levi (1469-1549), called Elias Levita by Latin authors, was a gifted Hebrew grammarian, teacher and editor/annotator of Jewish books for the Bomberg press of Venice. He also played an instrumental role in the development of Christian Hebrew scholarship, both by tutoring Christian pupils such as Cardinal Viterbo and by writing Hebrew grammar books and lexicons in Hebrew which were easily adapted to Christian use. The first of Levitas books to be translated into Latin, in this case by Sebastian Münster, appeared in this Basel 1525 printing. Münster, Paul Fagius, and Johannes Campensis edited or translated a number of Levitas works, printing them in Basel, Paris, Isny, Cracow, and Louvain. At least 26 more printings of Levitas books, either in Latin or as diglot texts with both the Hebrew original and Latin translation, would appear in print between 1525 and 1610, quite apart from the numerous printings of his works in Hebrew alone, intended for Jewish readers. Although he remained a Jew throughout his life, Levita had a tremendous impact upon Christian Hebrew scholarship through books such as this one.

Catechesis D. Martini Lutheri minor: germanice, latine, graece, & ebraice edita studio & opera M. Johannis Claii, Hertzberg; iterum recognita & emendata

Stephen Burnett

Martin Luther’s Small Catechism, written originally in German, was intended to instruct ordinary Christians in the proper understanding of the Christian faith through explanations of the Apostles Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments, and the sacraments. In 1570, the Catechism appeared for the first time in a polyglot form which included not only the original German, but Hebrew, Greek, and Latin translations of the text in parallel columns. This new edition was ideally suited to language instruction in schools since it included familiar texts in the less familiar biblical languages. While the text of the Ten Commandments could be copied from the Hebrew Bible, most of the catechism had to be translated into Hebrew for the first time. The copy held by the Center for Judaic Studies library is a good representative of this work in that it was printed at Wittenberg by the heirs of Johannes Krafft (Crato), a fairly successful Hebrew printer for the Protestant market. This firm produced 16 of the 25 printings of the polyglot catechism which appeared between 1570 and 1650, all except one of which were printed in Wittenberg. The perennial popularity of the polyglot catechism in Lutheran cities and territories demonstrates that Lutheran scholars too considered the study of Hebrew important, although their role in the development of Christian Hebrew scholarship has remained largely unacknowledged.

Sefer ʻAḳedat Yitsḥaḳ…

Seth Jerchower

The decades immediately preceding and ultimately culminating in the Spanish Expulsion were witness to ever-increasing efforts by the Iberian Church in episodes of conversion by coercion: Jews were forced to attend sermons to convince them of the errors of their faith. To counter this, the Aragonese rabbi Isaac ben Moses Arama (ca. 1420-1494) composed his own homilies and delivered them to the Jewish community. These homilies consisted of a philosophical defense of Judaism: the appeal of reason over the terrors of the establishment. Later, Arama collected and reorganized these sermons as his magnum opus, the `Akedat Yitshak. The title, which translates as The Binding of Isaac, is a fitting one, for indeed Arama masterfully binds the traditions and methods of midrashic exposition with those of philosophical demonstration. The ‘Akedah rapidly gained favor among a Jewish readership whose demography was ironically expanded by the events of 1492. It would also gain notoriety within Christian circles, where it was perceived as a slanderous work against Christendom, its dogmas and its institutions. Like many other Jewish works, particularly core ones such as the Talmud, lexica, commentaries, and entire sections of liturgy, it was liable to censorship.

Censorship as an official institution was a response to both the success of the printing press and the [arguably subsequent] threat of Protestantism. A first decree prescribing universal censorship was proclaimed in 1487 in a Bull issued by Innocent VIII. In 1516 a Bull by Leo X instituted the imprimatur, the pre-publication approbation. Universal enforcement would not occur, however, until the 1540’s, after two events that sanctioned its implementation: the relegation of all censorship matters to the General Inquisition in 1542 by Paul III, and the recommendation of the Council of Trent in 1546 for a more active enforcement. What followed, inter alia, was the Index librorum prohibitorum [Index of Prohibited Books], an en masse confiscation and “correction” of alleged illicit writings, Paul IV’s infamous Bull Cum nimis absurdum, and the burning of books, not least of which was the Talmud. In 1554 Julius III decreed that any Hebrew book not bearing the imprimatur fell subject to confiscation if it was deemed derogatory to Christianity. The book was given to a censor (often an apostate, who brought with him his knowledge of Hebrew; there is also evidence that faithful Jews played an ancillary role, possibly as an endeavour to save Jewish texts from obliteration) who would proceed to blot out the offensive passages. The final step was the placement of a “censor’s mark,” usually consisting of a signature, date, and brief declaration of examination. Despite an explicit provision in Julius III’s Bull, the books were typically not returned to their owners, but kept sequestered in church or convent libraries. Curiously, the same censors’ names today recur in Judaica collections throughout the world, yet represent a relatively brief albeit intense period of activity restricted to a relatively minimal area: the Papal State and the Savoy. After having occupied northern Italy (1796-98), Napoleon shut down the convents and monasteries of these regions, leading to an abandonment of the libraries, and a sudden boom for collectors.

Thesaurus linguae sanctae

Seth Jerchower

Pagnini, whose initial formation began under the tutelage of Girolamo Savonarola in Florence, is the likely emblematic albeit arcane figure of post-laurentian Christian Hebraism in Italy. His commentaries, grammars and translations were hailed by Christians and Jews alike, and his erudition and industry so impressed the Medicean Pope Leo X that he assumed the expenses of Pagnini’s Veteris et Novi Testamenti nova translatio (Lyons, 1527). The Thesaurus linguae sanctae is Pagnini’s translation of and exposition on the Biblical glossary Sefer ha-shorashim (Book of Roots) by David Kimhi, the preeminent medieval grammarian of the Hebrew language.

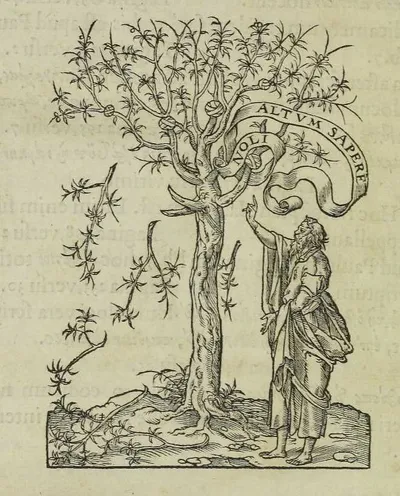

The noted printer’s mark of the Stephanus (Estienne) family of Paris epitomizes the attitudes of pre-Counter Reformation Christian Hebraism. Both the tree, a trope for Divine wisdom, and the motto, “Noli altum sapere,” are taken from Romans 11, verses 19-20: “Thou wilt say then, The branches were broken off, that I might be grafted in. Well; because of unbelief they were broken off, and thou standest by faith. Be not highminded, but fear.”

Meʾor ʻenayim

Joanna Weinberg

The Light of the Eyes established the foundations of critical Jewish historiography. Its author, the sixteenth-century Italian Jew Azariah de’ Rossi, was a polymath who was familiar not only with the texts of his own Jewish tradition, but also with Christian and pagan literature including comtemporary Christian Hebraists such as Sebastian M|nster, Augustinus Steuchus, and Pico della Mirandola. The book covers a wide range of topics including the origins of the Septuagint, Jewish chronology and the priestly vestments. In every subject de’ Rossi was able to innovate, taking heed of the relevant Jewish and Christian scholarship. Subsequent to his death, Christian theologians and historians often cited “Rabbi Azarias” alongside such reputable authors as Maimonides and ibn Ezra, and translated several chapters of his work into Latin. De’ Rossi’s reputation among Jewish scholars was established in the nineteenth century when the pioneers of the Wissenschaft des Judentums (Science of Judaism) hailed de’ Rossi as the “first true Jewish historian.”

Synagoga Iudaica: hoc est, Schola Iudaeorum in qua natiuitas, institutio, religio, vita, mors, sepulturaq[ue] ipsorum è libris eorundem; a M. Iohanne Buxdorfio…

Stephen Burnett

Johannes Buxtorf the elder taught Hebrew at Basel University from 1590-1629 and was justly known as one of the finest European Hebrew scholars of his day. His book Jewish Synagogue (Juden Schul, Basel, 1603) as one of the first serious attempts by a Christian scholar to portray traditional Judaism in a realistic way, explaining the laws governing Jewish life from cradle to grave, the Jewish week and the Jewish religious calendar using quotations from Joseph Karo’s Shulhan Aruk and Judeo-German popular works to back up his assertions. His goal in writing the book, however, was not to commend Jews for their faithfulness to Jewish law, but to criticize them for their departures from biblical law and practice. The Center for Advanced Judaic Studies library holds two different Latin translations of this work, but the more important of these was printed in Hanau in 1604, and reprinted in 1614 and 1624. This text was the one which made Buxtorf’s impressive analysis available not only to the learned Christian world, but also to R. Leon Modena of Venice who wrote his famous Historia de riti hebraici (1637) as a refutation of Buxtorf’s work.

Institutiones linguae hebraicae

Piet van Boxel

Robert Bellarmine wrote this Hebrew grammar, which was first published in Rome (1578), when teaching biblical exegesis at the Jesuit School in Louvain (1574-1576). Included in the grammar is the Exercitatio Grammatica in Psalmum XXXIII, a word for word explanation of the Hebrew text of the Psalm. For his grammar Bellarmine made ample use of Jean Cinqarbres’ Institutiones in Linguam Hebraicam (Paris, 1559). Later editions of Cinqarbres’ grammar include also Bellarmine’s Exercitatio (Paris: 1582, 1609, and 1619). Bellarmine, who had been a student of the Christian Hebraist Johan Willems (Harlemius) of the famous Collegium Trilingue, erected in 1515 on the initiative of Erasmus, became later one of the protagonists of the Counter-Reformation.

Opuscula hebraea, graeca, latina, gallica

Stephen Burnett

Anna Maria von Schurmann (1607-1678) was the child of a noble family of Protestant Flemish exiles who had fled the anti-Protestant persecution in the Spanish Netherlands. She was born in Cologne, but in 1615 the family moved to Utrecht. She received an excellent education from the tutors hired to teach her brothers, and soon proved to be both a gifted visual artist and an accomplished Latin poet. By the early 1620’s she had already become known as an excellent linguist and she developed a broad correspondence, receiving letters and poetry from scholars written in Hebrew, Latin, Greek, French and Dutch. She is reported to have been able to read Arabic, Aramaic, Syriac, Ethiopic, Turkish and Persian as well. Her teachers and friends were some of the best linguists in the Dutch Republic, including scholars such as Gispert Voetius, Andre Rivet, Friedrich Spannheim, and Joannes Beverovicius. She corresponded with Claude Saumaise, G. J. Vossius, and Daniel Heinsius, and theologians such as Voetius, Hornbeek, and Cloppenberg dedicated works to her. Her book, the Opuscula, edited by her friend Friedrich Spannheim, is a collection of her lesser writings, and appeared in three different printings. In 1653, at the height of her fame, she left the Netherlands and returned to Cologne to take care of family responsibilities. She then went into seclusion at a country estate, ceasing to answer her correspondents. In 1661, she became a follower and patroness of Jean de Labadie, once a Jesuit but by then a Protestant mystic who sought to create a new, purified Christian faith, a vision she too sought to fulfill until her death in 1678. Schurmann was able to gain entry into the rarefied world of the Republic of Letters because of her noble birth and her outstanding intellectual gifts, and as a result was able to become acquainted with the famous and learned university scholars who enjoyed such prominence in the learned world. She was one of the few female Christian Hebrew scholars in early modern Europe.

Horæ hebraicæ et talmudicæ

Jeffrey S. Shoulson

Considered by many to be the greatest English scholar of Jewish literature of his time, Lightfoot was skilled not only in Biblical Hebrew, but also in Mishnaic Hebrew and Talmudic Aramaic. He became Master of St. Catharine’s Hall, Cambridge, in 1643, and Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University in 1654. As a member of Parliament, Lightfoot was entrusted with overseeing and administering a large purchase of texts in several Semitic languages for Cambridge in 1647-48. This volume contains the first two installments of a work that was published serially between 1658 and 1674. Drawing extensively on Talmudic literature, the writings of Josephus, and other classical sources, the first half offers a detailed geography of all the locations in the Land of Israel mentioned in the Gospels. The second portion shows the Talmudic parallels and rabbinic background to the Gospel of Matthew. Later installments offered the same insights for the other Gospels, Acts, I Corinthians, and parts of Romans.

Liber Cosri

Adam Shear

Johannes Buxtorf “the younger” (1599-1664), the son of the elder Johannes Buxtorf (1564-1629), was professor of Hebrew in Basel. Much of his scholarly work was concerned with Hebrew linguistics and debates over the antiquity of the masoretic text of the Bible. Like his father, however, he also maintained an interest in post-biblical Judaism, and published a new edition of his father’s summary of Jewish practice, Synagoga Judaica (1661, repr. 1680.) The younger Buxtorf also developed a strong interest in Jewish theology, and early in his career, he published a new Latin translation of Maimonides’ Guide of the Perplexed (1629). One of his last works was this translation of Judah Halevi’s anti-philosophical defense of Judaism, the Book of the Kuzari, based on Judah ibn Tibbon’s Hebrew translation. The Kuzari, whose literary form was inspired by the eighth-century conversion of the Khazar people to Judaism, consists of an imagined dialogue between a rabbi and the Khazar king. Halevi’s work was popular among Jewish scholars for its arguments for the reliability of the Jewish tradition, and for the superiority of the Jewish people, the land of Israel, and Hebrew. The book also contains extensive discussions of Jewish history, doctrine, and law; the Hebrew language; and various scientific issues. Making use of a sixteenth-century commentary by Judah Moscato, a Mantuan rabbi, as well as other Jewish authors, Buxtorf’s extensive introduction discusses the Khazars, Halevi, as well as the content of the work. He also included Hebrew and Latin versions of letters between a later Khazar king and Hasdai ibn Shaprut (whose authenticity he doubted). One of Buxtorf’s major goals was to make this work accessible to Christian scholars who desired knowledge of Jewish thought but were not themselves Hebraists. In addition to his own notes explaining the text, a citation index, and a detailed subject index, he appended relevant excerpts (in Latin translation) from works by various Jewish authors including Isaac Abravanel and Azariah de Rossi. Buxtorf’s Liber Cosri made its way into numerous scholarly libraries in the later seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and was instrumental in bringing both Halevi’s treatise and the story of the Khazar conversion to the attention of the Christian scholarly world. Buxtorf’s work also did not go unnoticed by Jews: in late eighteenth-century Berlin, Moses Mendelssohn used the margins of this work to copy a commentary on the Kuzari by his teacher, Israel Zamosc.

The present state of the Jews

Harvey Goldberg

Lancelot Addison was an Anglican clergyman who was assigned to accompany English troops stationed on the Northern Coast of Morocco. There, he came into contact with local Jews, and utilized the experience to write about Jewish life. His The Present State of the Jews (more particularly relating to those in Barbary) was published in the decades after Jews were formally permitted to resettle in England. It was reprinted several times, suggesting that the book attracted interest as a source of information on the Jews. A later publication of his on Islam identifies Addison as the author of The Present State of the Jews, further pointing to the recognition that the book achieved. A striking feature of the publication is its frontispiece, which depicts a “native” holding a banner proclaiming ‘The Present State Of The Jews In Barbary’. No explanation is attatched to the illustration. Scholars have pointed out that part of Addison’s book simply repeats material found in the English translation of Johannes Buxtorf’s work, The Jewish Synagogue, or an Historical Narration of the State of the Jewes (Synagoga Judaica, London, 1657). It is thus likely that when Addison did not have information from his own experience in North Africa, he “cribbed” from Buxtorf who recorded Jewish life in Central Europe. The title page also cites an annex to the book, a Discourse of the Misna, Talmud and Gemara.

Kabbala denudata

Allison Coudert

The Kabbala denudata offered the Latin reading public selections from the most famous kabbalistic work, the Zohar, while providing other kabbalistic treatises and extensive commentaries to help the reader understand this notoriously difficult text. The editor and translator of the work, Christian Knorr von Rosenroth (1636-1689) was an accomplished Hebrew and Aramaic scholar, who considered the Kabbalah the single most important source for recovering the ancient wisdom (prisca sapientia) that God imparted orally to Adam before the fall. This is the message of the frontispiece, which shows the Kabbalah as a beautiful maiden running towards the palace of secret wisdom with the keys to both the Old and the New Testaments hanging from her wrist.

Ceremonies et coustumes qui s’observent aujourd’huy parmy les juifs …

Guy Stroumsa

Leone (Yehudah Arieh) Modena’s I riti degli Ebrei…, written forthe King of England about 1617, and published in Paris (without its author’s permission) in 1637 by the Christian Hebraist Jacques Gaffarel, is the first ethnographic description of Jewish customs written by a Jew in the modern times , with a Christian readership in mind. The Riti were translated into various languages, and remained for a long time one of the msot important sources of knowledge about Judaism. The great Christian Hebraist Richard Simon translated it into French in 1674, and in a second edition added his own treatise comparing, from a chronological as well as structural viewpoint, Judaism and Christianity.

Schediasma historico philologicum de Judaeorum pseudo-messiis

Michael Heyd

Johann Lent was a doctor of Theology and professor of Oriental Languages and Church history in the Protestant Academy of Herborn, Germany. The book, An off-hand historical study of Jewish false Messiahs, was first published in 1683 and is quite rare, as is the second 1697 edition, which the Center for Judaic Studies library possesses. The book consists of a long list of Jewish Pseudo-Messiahs, beginning with Bar Khokhba, and including two chapters (pp. 76-102) on Sabbatai Zevi, chapters which are largely based on the earlier accounts of Paul Rycaut and Thomas Coenen. It ends with a short report of the Pseudo-Messiah Mordechai from Eisenstadt who appeared in 1682. The book was quite influential and often quoted in Christian-Jewish polemics of the following generation.

Libro yntitulado Nisahon, traduzido por David Pardo

Israel Yuval and Ora Limor

Sefer ha-Nitsahon (Book of Contention or Victory) is a polemical work against Christianity and Jewish heresies written by Rabbi Yom Tov Lipmann M|lhausen (d. 1421) around 1401, probably in Prague or its vicinities. Lipmann traveled to other places in Bohemia and in the Rheinland as well. On several occasions he was involved in religious disputations, defending his faith and his community against Christian attacks. He is one of the first in medieval German Jewry to study philosophy and Kabbalah along with rabbinical scholarship. Although the author of many treatises - halakhic, liturgical, and hermeneutical - he is known to posterity mainly for his polemical Sefer ha-Nitsahon.

The book gained a wide circulation among Jewish readers in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Forty-five manuscripts of the book survived - a very impressive number even by Christian standards. The work attracted Christian attention as well: Johann Pfefferkorn considered it to be the ultimate anti-Christian text and a major obstacle on the Jews’ way to conversion. In the list of confiscated Hebrew books in Frankfurt for 1509, the municipal notary recorded a declaration the Jews had made concerning the Sefer ha-Nitsahon: Kein haben wir davon (“We have no copies of it”). For many years Christian polemicists worked in vain to lay their hands on manuscripts of the book. In 1644, Theodor Hackspan, a professor of Hebrew at the University of Altdorf, succeeded in getting a copy, and he sat down a few of his Hebrew students to copy the book, and soon the editio princeps came into being. The Hebrew knowledge of the scribes was far from perfect, and the edition is full of mistakes.

Soon after becoming available, sections of the book were translated into Latin, and a full translation appeared in 1645. In 1674 Johann Christoph Wagenseil succeeded Hackspan as Professor of Languages in Altdorf, and during the same year he published his Correctiones Lipmannianae according to two other manuscripts he managed to obtain. In his famous collection of Jewish polemical literature, the Tela ignea Satanae (‘Satan’s Fiery Arrows’), Wagenseil included responses to the Sefer ha-Nitsahon . Three Jewish editions appeared in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A critical edition is in preparation by Ora Limor and Israel Yuval.

According to the title and to the information given in the translator’s introduction, the manuscript here on display contains a Spanish translation of Sefer ha-Nitsahon by R. Yom-Tov Lipmann Mühlhausen. The translation was made by the cantor David Prado in London, in 1695. In fact the manuscript contains two different works, neither of them being Lipmann’s Nitsahon. The first is the Nitsahon Vetus, i.e. the older Nitsahon, an anthology of Jewish Ashkenazic anti-Christian polemic, probably written in Germany at the end of the 13th century, with several additions (some of which may have been derived from Lipman’s Nitsahon). The order of chapters does not always correspond to the known versions of the Nitsahon Vetus. It is impossible to tell whether the changes were made by the translator himself. It is also hard to tell why he ascribed the Nitsahon Vetus to Lipmann M|hlhausen, but it would seem that the confusion between these two works was quite common.

The second work in this manuscript, also translated by Prado, is the Sefer Toledoth Yeshu, a Jewish counter-biography of Jesus, which was very popular among Jews in Early Modern and in Modern Europe.

Reasons for naturalizing the Jews in Great Britain and Ireland

Jonathan Karp

John Toland (1670-1722), Deist philosopher and political writer,was born a Catholic in Londonderry and converted to Protestantism at the age of 16. His embrace of religious toleration, in tension with his powerful animus toward Catholicism, underlay Toland’s 1714 pamphlet advocating the naturalization of foreign-born Jews in Great Britain and Ireland.

Historians have traditionally viewed Toland’s Reasons as a “harbinger” of later Jewish emancipatory ideology. But the work is best seen as a Philo-Judaic tract promoting the author’s scheme to employ Jewish colonists as a political and military wedge against Catholic Jacobite insurrection. Jewish naturalization and colonization were in line with Toland’s depiction of contemporary Jews as inheritors of the civic and military virtues embedded in the ancient “Respublica Mosaica,” a model of ancient constitutionalism marked by natural law and religious freedom for non-Jews (outlined in greater detail in Toland’s 1718 Nazarenus or Jewish, Gentile and Mohametan Christianity). Toland produced his Reasons at a moment (the Autumn of 1714) when Whigs had grown euphoric over the recent succession to the British Crown of the Protestant Hanoverians, placing theTory Party on the defensive and offering - or so Toland believed - a unique opportunity for expanded religious freedom. While Toland’s Reasons exerted no immediate impact on the status of Jews in Britain, it can be viewed as marking a high point in the intellectual history of a genuine Philo-Semitism, one premised on the presumed historical virtues of Jews and Judaism while eschewing all Christian missionary intent.

Jüdisches Ceremoniel, oder, Beschreibung dererjenigen Gebräuche

Yaakov Deutsch

This book is an example of a specific genre in the writings of Christian Hebraists, which includes works that describe the customs, ceremonies and rituals of contemporary Jews. Like many writers of these books, Kirchner was a convert. Beside this book he published a work in 1719 that was aimed to help with the conversion of the Jews, entitled Lehar’ot or emet la-yehudim. The Jüdisches Ceremoniel was originally published in 1717 and later on was revised and enlarged by Sebastian Jacob Jungendres (1684-1765). According to Jungendres the original work by Kirchner was inaccurate and biased because he wanted to prove the evilness of the Jews. Another addition to this imprint are 27 engravings that portray various customs and ceremonies held by the Jews. The book was published at least eleven times between 1717 and 1734, including a Dutch translation, and was reprinted in 1974 by Olms and in 1999 by the Reprint-Verlag, Leipzig.

Joannis Seldeni jurisconsulti Opera omnia, tam edita quam inedita

Jason Rosenblatt

John Selden (1584-1654), the most learned person in England in the seventeenth century, was a lawyer, an antiquarian, a member of Parliament,and the greatest expert of his day on British legal matters. A polymath, he also wrote a half dozen rabbinic works, some of them immense, which respect, to an an extent remarkable for the times, the self-understanding of Judaic exegesis. De Diis Syris (1617), an analysis of the pagan gods of the Hebrew Bible, constitutes a pioneering study of cultural anthropology and comparative religion. Its literary influence extends to the work of Ben Jonson and to the list of pagan gods in John Milton’s Nativity Ode and Book 1 of Paradise Lost. De Successionibus (1631) addresses the question of intestate succession according to Jewish law. De Successione in Pontificum Ebraeorum (1638) explores the laws relating to the ancient Jewish priesthood. Uxor Ebraica (1646) analyzes the theory and practice of the Jewish laws of marriage and divorce, which Selden admired. On the very last page he suggests parenthetically (because he loved to bury the lead) that the canon law of divorce still in force in England be reformed and brought more closely into conformity with Jewish law. Selden’s motto was “Above all things, liberty,” and De Synedriis Veterum Ebraeorum (1650-53), a study of the Sanhedrin written shortly after the execution of Charles I, contains a remarkable Maimonidean discussion of whether that court could try kings not only for crimes like murder that anyone could commit but also for those which only kings could commit. Occupying 1,132 huge folio columns in the Opera, De Synedriis deals primarily with the constitution of Jewish courts, including the Sanhedrin, which, as Selden notes pointedly,was not priestly in composition. Its understated argument is thoroughy Erastian, demonstrating that matters at present under the jurisdiction of ecclesiastical courts in England were in ancient times decided by Jewish courts that could well be called secular. De Jure Naturali et Gentium (1640), surely one of the most genuinely philosemitic works produced by a Christian Hebraist in early modern Europe. Selden accepts the universal validity of the praecepta Noachidarum, the seven Noachide laws, which for him constitute the law of nature. Selden bases his theory on the Talmud, which for him records a set of doctrines far older than classical antiquity. Natural law consists not of innate rational principles that are intuitively obvious but rather specific divine pronouncements uttered by God at a point in historical time. Selden discusses the rabbinicidentification of natural law with the divinely pronounced Adamic and Noachide laws, considered by rabbinic tradition as the minimal moral duties enjoined upon all of humankind. While he accepts the authority of this non-biblically rabbinic law, he dismisses the biblical ten commandmentsas of purely Jewish interest. Readers of every stripe made amazingly different uses of Selden’s scholarship in De Jure, which looks back to Grotius and forward to Hobbes, and influences readers as different as Isaac Newton, the zealously antiprelatical Independent Henry Burton (one of the Tower-Hill martyrs shorn of his ears by Archbishop Laud), the Presbyterian John Lightfoot (himself a Hebraist, he called “the great Mr. Selden the Learnest man upon the earth”), the proto-deist John Toland, and Bishop Stillingfleet. The last volume of the Opera contains Selden’s work in English, including his famous Table-Talk. According to David Ogg, Selden sought “not fame but truth in an erudition more vast than was ever garnered by any other human mind.”

Algemeine Welt-Historie von Anbeginn der Welt bis auf gegenwfrtige Zeit (Universal history, from the earliest account of time)

Nils Roemer

The Algemeine Welthistorie, published by the theologians and historians Siegmund Baumgarten and Johann Semler in Halle between 1744 and 1765, provides an elaborate account of Jewish history from antiquity to the end of the seventh century. This encyclopedic and multi-volume universal history represents a truly unique moment in the development of modern historiography, since before the rise of modern historicism, historic accounts of the world restricted the Jewish past to the Biblical period.

La Bible enfin expliquée par plusieurs aumôniers de S. M. L. R. D. P.

Adam Sutcliffe

Voltaire’s hostility towards Judaism is notorious. He repeatedly returns in his extremely prolific writings to a cluster of favorite themes: the absurdity and immorality of the Old Testament and the primitivism, historical insignificance and arrogance of the Jewish people. Although his aphoristic style of writing contrasts markedly with the cautious erudition of Christian Hebraism, his anti-Judaic polemics were nonetheless to a large extent based on his own engagement with, and critique of, this tradition. In La Bible enfin expliquée (1776) - one of his last major works - Voltaire put forward his most systematic satire of both Christian and Jewish biblical exegesis. His title is manifestly ironic: his concern is not to ‘explain’ the Bible, but systematically to expose its absurdities, contradictions and ethical shortcomings. Focusing almost exclusively on the Pentateuch, he seldom misses an opportunity to highlight instances of Jewish barbarism or hypocrisy. These textual attacks are at times explicitly broadened out to apply to Jews of all eras: ‘still in our times’, he writes, ‘the people of this nation are extremely dirty and stinking.’

This text is perhaps the most rhetorically powerful statement of the repudiation of Hebraist scholarship by the philosophes of the High Enlightenment. Voltaire and his allies regarded rabbinic literature as the very quintessence of obscurantism and pedantry, and as such the defining polar opposite of their own self-consciously engaged intellectual values.

Selected Bibliography

-

Burnett, Stephen G. From Christian Hebraism to Jewish Studies: Johannes Buxtorf (1564-1629) and Hebrew Learning in the Seventeenth-Century. (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1996)

-

. “Christian Hebrew Printing in the Sixteenth Century: Printers, Humanism, and the Impact of the Reformation,” in Helmantica (51/154 (April 2000): 13-42).

-

Coudert, Allison P. The Impact of the Kabbalah in the Seventeenth Century: The Life and Thought of Francis Mercury van Helmont. (Leiden: E. J. Brill,1999)

-

Friedman, Jerome. The Most Ancient Testimony: Sixteenth-CenturyChristian-Hebraica in the Age of Renaissance Nostalgia. (Athens, OH : Ohio University Press, 1983)

-

Goldish, Matt. Judaism in the Theology of Sir Isaac Newton. (Dordrecht and Boston: Kluwer Academic, 1998)

-

Hames, Chaim. The Art of Conversion: Christianity and Kabbalah in the Thirteenth Century. (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2000)

-

Horowitz, Elliot. “A Different Mode of Civility’: Lancelot Addison on the Jews of Barbary,” in S_tudies in Church History 29, Christianity and Judaism papers read at the 1991 Summer Meeting and the 1992 Winter Meeting of the Ecclesiastical History Society,_ edited by Diana Wood (Cambridge, Published for the Ecclesiastical History Society by Blackwell Publishers, 1992: 309-325)

-

Katchen, Aaron L. Christian Hebraists and Dutch Rabbis: Seventeenth Century Apologetics and the Study of Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1984)

-

Kessler Mesguich, Sophie. “L’enseignement de l’hebreu et de l’arameen a Paris (1530-1560) d’apres les oeuvres grammaticales des lecteurs royaux,” in Les Origines du College de France (1500-1560), Editor Marc Fumaroli (Paris: College de France / Klincksieck, 1998, 357-374)

-

Kunz, Marion L., and Guillaume Postel. Prophet of the Restitution of All Things. His Life and Thought. (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1981)

-

Lloyd Jones, G. The Discovery of Hebrew in Tudor England: A Third Language. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1983)

-

Loewe, Raphael. “Hebraists, Christian,” in Encyclopaedia Judaica (Jerusalem / New York, 1971-1972)

-

Manuel, Frank. The Broken Staff: Judaism through Christian Eyes. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992)

-

Modena, Leone. Les Juifs presentes aux chretiens: ceremonies et coutumes qui s’observent aujourd’hui parmi les Juifs., Editor and Translator Richard Simon. With new introduction by Jacques Le Brun and Gedaliahu [Guy] Stroumsa (Paris : Les Belles Lettres, 1998)

-

Popper, William. The censorship of Hebrew books., Introduction by Moshe Carmilly-Weinberger (New York, Ktav Publishing House, 1969)

-

Roussel, Bernard and Gerald Hobbs. “Strasbourg et y a l’Ecole Rhenane d’Exegese (c. 1525-1540),” in Bulletin de la Societe de l’Histoire du Protestantisme Francaise (135/1 (1989): 36-53)

-

Sonne, Isaiah, 1887-1960. Expurgation of Hebrew books—the work of Jewish scholars : a contribution to the history of the censorship of Hebrew books in Italy in the sixteenth century. (New York : New York Public Library, 1943)

-

Steinschneider, Moritz. Christliche Hebraisten. Nachrichten uber mehr als 400 Gelehrte, welche uber nach biblisches Hebraisch geschrieben haben. (Hildesheim: Dr. H. A. Gestenberg, 1973)

-

Van Rooden, Peter T. Theology, Biblical Scholarship and Rabbinical Studies in the Seventeenth Century: Constantijn L’Empereur (1591-1648) Professor of Hebrew and Theology at Leiden. (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1989)

-

Wirszubski, Chaim. Pico della Mirandola’s Encounter with Jewish Mysticism. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989)

-

Zinguer, Ilana, ed. L’Hebreu au Temps de la Renaissance. (Leiden: E. J.Brill, 1992)

Contributors

-

Piet van Boxel - Leo Baeck College, King’s College/CAJS 2000

-

Stephen Burnett (Sefer ha-Diḳduḳ… | Catechesis… | Synagoga Iudaica… | Opuscula hebraea…) - University of Nebraska/CAJS 2000

-

Allison Coudert - Arizona State University/CAJS 2000

-

Yaakov Deutsch - Hebrew University/CAJS 2000

-

Harvey Goldberg - Hebrew University/CAJS 2000

-

Chanita Goodblatt - Ben Gurion University/CAJS 2000

-

Chaim (Harvey) Hames - Ben Gurion University/CAJS 2000

-

Michael Heyd - Hebrew University/CAJS 2000

-

Seth Jerchower (Aldi Pii Manutii… | Psalterium… | Sefer ʻAḳedat… | Thesaurus linguae…) - University of Pennsylvania

-

Jonathan Karp - State University of New York, Binghamton/CAJS 2000

-

Fabrizio Lelli - Theological Faculty of Central Italy/CAJS 2000

-

Ora Limor (Pugio Fidei… | Nisahon…) - Open University/CAJS 2000

-

Nils Roemer - University of Southampton, England/CAJS 2000

-

Jason Rosenblatt - Georgetown University /CAJS 2000

-

Adam Shear - University of Pennsylvania/CAJS 2000

-

Jeffrey S. Shoulson - University of Miami/CAJS 2000

-

Guy Stroumsa - Hebrew University/CAJS 2000

-

Adam Sutcliffe - University of Illinois, Urbana/CAJS 2000

-

Joanna Weinberg - Leo Baeck College, Oxford University/CAJS 2000

-

Israel Yuval - Hebrew University/CAJS 2000

Special Thanks

Special thanks to Etty Lassman for her assistance and expertise in producing the images for this exhibit, and to Arthur Kiron for his assistance in its organization.