Expanding Jewish Political Thought: Beneath, between, before, & beyond the state

Introduction

Over the course of their history, Jews have embraced a wide range of ideological views and operated within a variety of political contexts. These experiences have generated a rich body of political thought, but there has been an ongoing need to advance such thought in light of new developments in political theory and a changing world beyond academia. One way forward is to continue to stretch the boundaries of Jewish political thought in ways that intersect with the study of law, religion, history, literature, and other subjects, or that approach the subject in a comparative framework. During the 2016–2017 academic year, The Katz Center brought together scholars working in fields from ancient to contemporary philosophy and theory to unsettle regnant paradigms of power and statehood. They drew upon a wide variety of sources and interdisciplinary methodologies to challenge established understandings of Jewish political history.

Exhibit

Hannah Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism

John Ackerman

At a time when contemporary political developments have been attracting new readers to Hannah Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism, it is worth revisiting Arendt’s argument in the book’s first volume, which looks to aspects of Jewish history—namely, relations between Jews and the societies and states amid which they lived—to explain the role that antisemitism came to play in mid-twentieth-century totalitarianism. In doing so, it makes several claims that have been contested fiercely by scholars of Jewish political history. Among these is the assertion that the Jewish people “began its history with a well-defined concept of history and an almost conscious resolution to achieve a well-circumscribed plan on earth and then, without giving up this concept, avoided all political action for two thousand years” (p. 8).

Arendt’s critics have interpreted this claim as a charge of “Jewish passivity” in the face of political exigencies and produced evidence to refute it. However, a careful reading of the “Antisemitism” volume, reinforced by many of Arendt’s other writings, shows that what was actually at stake for Arendt—and for Jewish politics—was something else. The avoidance of political action is hardly unique to the Jews, in Arendt’s eyes; it similarly characterizes the more than two thousand years since the first, Greek political philosophers “wished to turn against politics and against action” to secure certainties politics cannot provide (Arendt, The Human Condition, p. 195). The tendency to avoid and displace politics is a constant theme in Arendt’s writings. What Arendt critically narrates in the first volume of The Origins of Totalitarianism is a history of Jews (not all Jews, but certain Jewish elites who played an outsized role in relations between Jews and non-Jews) actively pursuing a strategy of vertical alliances that had the effect, in the short and longer term, of shielding Jews from political encounter with their non-Jewish neighbors. These alliances shored up patterns of rule (by Jewish “notables”) and exception (see Origins, pp. 62-64), that, as Arendt argues throughout her work, are often mistaken for politics but are actually at odds with it, patterns that easily become institutionalized and serve to benefit some at the expense of many others, and of politics as such.

Arendt’s argument, here and elsewhere, is that the avoidance of politics has ultimately proven and will continue to prove catastrophic. Politics requires continuing encounter and the ability to act together with—and where necessary, against—others different than ourselves, on the basis of judgments that can only be made where such encounter across lines of difference occurs. As Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianismshows, it is the very possibility of this kind of political encounter that totalitarianism destroys, and it is this possibility that must be reconstituted if there is to be politics in totalitarianism’s wake. It is an argument that is just as relevant now as it was in 1951, including for the project of rethinking and expanding Jewish political thought.

A Jewish Genealogy of Political Economy

Samuel Brody

Pictured here are the opening pages of On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, originally published in England in 1817. Its first American edition, shown here, arrived only two years later. The author, David Ricardo (1772-1823), was one of the foremost of the classical political economists, usually ranked with Adam Smith, James Mill, and Thomas Malthus (the latter two of whom were his friends and correspondents). He was born into a Sephardic family that had moved to London from Amsterdam, and as a youth he accompanied his father Abraham to the Jews’ Walk of the London bourse, pursuing an early career as a stockjobber. His marriage to Priscilla Ann Wilkinson, a Quaker, meant separation from the Jewish community, and his new identification as Unitarian meant that he was later eligible for a seat in the House of Commons (although legal action was required to exempt him from the Anglican rite).

Unlike Smith, who made his name as a professor of moral philosophy with his Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) before turning to the Wealth of Nations (1776), Ricardo comes to prominence with treatises on bullion and corn prices. And in contrast to Malthus, whose notorious Essay on the Principle of Population (1798) contains probing theological inquiries, one searches Ricardo’s Principles in vain for any hint that the problem of “value” has roots in moral discourse and significance for philosophy and religion. Indeed, Ricardo seems to come out of the blue as a secular economist. But for precisely this reason, his work can stand as a fascinating entryway into the story of the secularization of economic thought, and a marker of the paths to social and financial success open to (former) Jews in the England of the early nineteenth century.

Reading Zionist Texts: the Pathos of Historical Contingencies

Julie Cooper

Conducting archival research, one is often confronted with the pathos of history—the contingencies that render some texts lost or forgotten, while others are remembered and canonized. Moreover, some of the books that we remember bear traces of the circuitous paths by which they made their way into archival collections, while others betray no hints about their provenance, about the chains of scholarly transmission that brought them to the Katz Center.

This year, I devoted most of my time to reading Zionist texts from the first half of the twentieth century. On two occasions, I retrieved books from the stacks only to find that their pages were uncut, suggesting that I was the first person to read the Katz Center’s copy of these works (Hillel Zeitlin, Baruch Spinoza: His Life, Works, and System (1900) [Hebrew] and Hans Kohn, Die Politische Idee des Judentums (1924)). The excitement of discovery was tempered by a sadness that these books had sat unread for so many years.

Several weeks later, I received a copy of Hans Kohn’s History of the Zionist Idea (1929) [Hebrew] from interlibrary loan. On the inside back cover, I found an old circulation card listing the book’s previous borrowers. Only one name was listed—that of Arthur Hertzberg, the editor of the influential anthology of Zionist writings The Zionist Idea (first published in 1959). In many ways, Hertzberg’s project mirrors that of Kohn—both sought to provide a concise introduction to the various schools of Zionist thought. Yet Hertzberg wrote in English, after the establishment of the State of Israel, and, consequently, offers a radically different account of the most influential Zionist thinkers and the most salient ideological debates. I can venture hypotheses as to why Hertzberg was drawn to Kohn’s work and how it may have influenced him, but they remain highly speculative, as the circulation card conveys no information other than the fact that Hertzberg once borrowed the book.

While researching the work of Jacob Klatzkin (1882-1942), however, I stumbled upon unexpected evidence of concrete engagement on the part of at least one of the text’s prior readers. Dedicated to the project of developing a Hebrew philosophical idiom, Klatzkin is best known for his Otzar Ha Munahim Ha Philosophiim (1928) and his Hebrew translation of Spinoza’s Ethics, Torat ha-midot (1924). Some of Klatzkin’s Hebrew philosophical essays and aphorisms were published in English as In Praise of Wisdom (1943). When leafing through a library copy of In Praise of Wisdom, I was surprised to find the three index cards pictured at left—consecutive cards from the “A” drawer of a defunct library card catalogue—left by a prior reader. On the back of these cards from the old card catalogue, the reader has jotted key biographical and bibliographical details about Klatzkin, as well as a brief summary of Klatzkin’s analysis of the modern Jewish predicament and his disputes with his teacher Herman Cohen and with Ahad Ha’am. On the third card, the reader has recorded a shorthand for referring to two other Jewish thinkers from the period, Moshe Zeev Sole and Samuel Scheps. I do not know who jotted these notes or whether his/her research bore fruit, but it is gratifying to think that we are engaged in a serendipitous scholarly conversation about modern Jewish philosophy and political thought. I display the cards here as a testament to my anonymous interlocutor and his/her scholarly contributions.

Political Affairs—of State and Family—in a 19th-century Italian Commentary on Rabbinic Literature

Lois Dubin

Exegetical commentaries on Biblical and rabbinic texts are a rich source for Jewish political thinking. Benedetto Frizzi’s Petah Enayim (1st ed., 3 vols., Livorno 1815; 2d ed., 7 vols., Livorno 1878-81) provides an excellent example. Frizzi (1756-1844), a physician and wide-ranging scholar in northern Italy, wrote this commentary on the Ein Ya’akov, the 16th century collection of Talmudic Aggadah, in the spirit of Enlightenment science and natural philosophy. Even while calling for rationalist exegesis and social reform, he was committed to presenting classic Jewish teachings as relevant to modern concerns. Both excerpts from vol. 6, written around 1825, comment on passages in the Talmudic tractate Sanhedrin, and mention other works of his, in Italian, that treat political matters. Figure 1 shows the title page of vol. 6, from the 2nd edition.

Figure 2: The excerpt on p. 78a (re: Sanhedrin 20b) refers to his book Diritto Pubblico Mosaico (1811; full title Dissertazione sulle leggi mosaiche relative al pubblico diritto) and discusses constitutions, kings and despots, including King Solomon and Emperor Napoleon. Frizzi, like many others, often viewed contemporary events through a Biblical lens, while also projecting contemporary issues backward onto the Bible itself. Indeed, to mix together religion and politics, past and present, is a persistent temptation of Jewish political thinking

Figure 3: The excerpt on p. 81a (re: Sanhedrin 22a) refers to his six-volume book Dissertazione di Polizia Medica sul Pentateuco (1787-90), in particular vol. 3 on marriage, and discusses how divorce—though regrettable—is sometimes the best solution to marital quarrels and enmity.

Throughout his commentary, Frizzi addresses politics on both planes—the macro public realm of state and law, and the micro level of private lives, family, and marriage and divorce. In one passage, Frizzi states that Jewish law should treat women more fairly with regard to divorce and inheritance so as not to lag behind contemporary Habsburg, Prussian, and English laws.

Thus Frizzi’s Petah Enayim offers a rich potpourri of Jewish political thinking that weaves together Biblical and rabbinic exegesis with 18th-19th century social criticism and political ideas about rights, citizenship, and empancipation. For more on Frizzi’s ideas on love and marriage, you may consult another rare book in the Katz Center library: Hezekiah David Bolaffio’s work, Ben Zekunim (Livorno, 1793, part 2, p. 49), a collection of Halakhah and Hebrew poetry, which includes a poem by Frizzi on the qualities of an ideal wife!

Musical Utopia and Political Life: Ernst Hermann Meyer

Golan Gur

This photograph shows Ernst Hermann Meyer (1905-1988) composing at the piano in Berlin-Köpenick around 1970. All but forgotten today, Meyer was a key figure in the musical and cultural life of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR). A composer, musicologist, and a university professor, he belonged to a small but prominent group of Jewish émigré intellectuals who moved to East Germany after 1945. This group included philosophers, composers, and authors such as Paul Dessau, Anna Seghers, Hans Mayer, and Ernst Bloch (both Mayer and Bloch later left for West Germany). Like other members of this group, Meyer’s decision to move to the GDR was motivated not only by the prospect of professional opportunities, but also—and perhaps primarily—by a strong, if in retrospect naive, belief that the new communist German state represented the “better Germany” and offered an opportunity to establish a democratic and just society devoid of the malaises of capitalism and nationalism.

Meyer’s family background was typical of the Berlin Jewish middle class with its strong trust in culture and learning. His father was a medical doctor who served in WWI and his mother was a painter who had studied with Max Liebermann. One of Meyer’s most vivid childhood memories in connection with music was playing the violin with and for Albert Einstein who was a friend of his parents. Meyer studied composition with Paul Hindemith and completed his doctoral studies in musicology at the University of Berlin. During the 1930s, he came into contact with Hanns Eisler and his historical-materialist theory of music. Following Hitler’s seizure of power, Meyer used an opportunity to lecture in Cambridge in order to flee Nazi Germany. While in Great Britain, he continued to teach and compose and was active in various antifascist exile organizations. He moved to East Berlin in 1949 to take a position as Professor of Music Sociology at Humboldt University.

As a musicologist, Meyer was one of the pioneers of the social history of music. His direct models for this kind of research were the social histories of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. His study of early English Chapter Music is still valuable today. His positions on the aesthetic problems of contemporary music, however, are more likely to raise objections. In his writings and speeches, he propagated the official Soviet doctrine of Socialist Realism as the proper approach for contemporary musical production. Meyer himself followed this line in much of the music he composed from the 1950s on. A great part of his creative production in the GDR was dedicated to vocal compositions of a political nature, but he also composed film scores as well as large instrumental works such as the symphony Kontraste, Konflikte, a work containing moments of conflict and gloomy expression, apparently in contrast to the aesthetic imperatives of Socialist Realism. Some of Meyer’s musical compositions, such as his Mansfeld Oratorio, evoke the memory of the Jewish Holocaust but almost always from the viewpoint of the GDR’s national myth of antifascist resistance with its emphasis on economic relations as the basis for WWII and the rise of National Socialism (thus, distorting, or at least downplaying, the ideological background of National Socialism in antisemitism).

Meyer died in October 1988, a year before the fall of the Berlin Wall and the final collapse of the Soviet Union. Being a committed communist for most of his adult life and a member of the Central Committee in the GDR, the way in which his life work is assessed today stands in direct relation to how the East German regime is viewed. Was he unaware of the extent of oppression in the GDR? Did he wholeheartedly believe in the system and its ideology? These questions must remain unanswered, but Meyer is one of many who, in their belief in the possibility of a perfect society, used the arts to promote a political utopia.

Women of the Wall

Yuval Jobani

The “Women of the Wall” is a multi-denominational Jewish feminist group that seeks legal permission to perform, at the women’s section, practices reserved solely for men under the current arrangements at the Western Wall; namely to pray collectively and read aloud from a Torah scroll while wearing fringed prayer shawls. Historical surveys of prayer practices at the Western Wall in fact show that several gender-related arrangements currently in place at the site are not actually traditional. Most noticeably, perhaps, is the gender divider. This photograph, by Felix Bonfils, as do an abundance of other documentations from the late 19th and early 20th century, illustrates the lack of a formally organized and constant separation of men and women at the Western Wall. The two sexes were frequently depicted together, at times only a few feet away from each other. Gender separation practiced at the Western Wall today, therefore, stems from relatively late modifications to the prayer arrangements that had been maintained at the site for centuries.

James Harrington’s Proposal for Jewish Sovereignty

Meirav Jones

James Harrington’s Commonwealth of Oceana, of which a first edition from London, 1656 can be found in the Kislak Collections, is usually studied as an important text in the history of modern political thought for its bringing Roman republicanism and Machiavellian ideas to early-modern England in its only “republican” period. But those interested in Jewish politics and Jewish political thought will find this work interesting for another reason: It contains the a proposal for modern Jewish sovereignty, two-hundred years before this idea is usually considered to have entered modern political discourse.

Harrington’s proposal is that rather than incorporate Jews into England, which Cromwell was considering as Harrington was writing, Jews should be settled in Ireland, displacing Ireland’s (Catholic) population as they gathered there from the corners of the earth. The proposal was that Jews should be allowed to live there under their own laws and institutions, with an army to protect them, and that this arrangement would be for them and their heirs in perpetuity.

The proposal is built on three foundations:

The first foundation is “political Hebraism”. As political thinkers from the mid-sixteenth century had argued, Jews held exemplary political, economic, and agricultural wisdom. Harrington was the first to suggest that this wisdom could be employed by contemporary Jews towards running their own state.

The second foundation is the political-theory discussion of the role of religion in stabilizing sovereignty. Since Bodin’s founational work, theorists consistently argued, with few exceptions, that the modern state required some degree of conformity to civil religion for its stability, and the Jews were considered a people who would not conform.

The third foundation is the debate surrounding the reintrodcuton of the Jews to England taking place in mid-seventeenth century England. This debate is likely what brought Harrington to go further than any other theorist in providing a concrete proposal for placing the Jews in the modern world of states: the matter was urgent immediately following the Whitehall conference (convened in 1655 to debate the readmission of Jews to England). “To receive the Jews after any other manner into a common-wealth were to maim it,” wrote Harrington, while realizing that his proposal would have been more pertinent “had it bin thought of in time.”

The reader interested in Harrington’s proposal should read the excerpt provided here, with the following guidelines: Oceana is Harrington’s model England, Marpesia his model Scotland, and Panopea his model Ireland.

Cyrus Adler and the Politics of Jewish Philanthropy at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919

Rebecca Kobrin

This letter to Boris (Bernard) Bogen, head of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in Poland, along with Adler’s larger diary, illustrates the ways in which American Jews involved themselves in international political discussions following the Great War. American Jews, who sat at the table in the Paris Peace Conference, hoped to make the world safer for Jews. As this letter states, men like Adler were alarmed by the eruption of anti-Semitic violence in Poland, which many believed could become a liberal multi-ethnic political economy. Adler saw Poland as a great experiment in modern Jewish politics: a republic where Jews were not only citizens, but constituted a key minority voting bloc in the largest multi-ethnic East European state. He writes to Bogen, because the American Joint Distribution Committee which he represented in Poland, exemplifies how American Jews used the formidable strength of their dollars to effect change in Poland.

While the intricacies of local politics caused the impact of American dollars to have differential effect in various locales in Poland, they gave men like Cyrus Adler, Jacob Schiff (also mentioned in the letter) and Boris (Bernard) Bogen a chance to spread their own cultural agenda. Wilson may have failed to convince the American government to involve themselves diplomatically in the politics of rebuilding in the region of Eastern Europe, it is clear that individual non-governmental organizations in America, like the JDC, and men like Cyrus Adler would assume the mantle of Wilsonian idealism as they distributed money and advocated for Jewish rights at the Paris Peace conference. This letter exemplifies why we must consider men like Adler—a private citizen using his economic might to affect change in the world around him—as we endeavor to expand the parameters of the Jewish political tradition.

Agamben’s Homo Sacer: icons of a new form of politics

Nitzan Lebovic

Giorgio Agamben’s Homo Sacer series—the first part published originally in Italian in 1995—places the figure of the Muselmann (the paradigmatic “Homo Sacer” or Sacred man) and her “naked life,” in the center of modern politics. It encounters the traditional political stress on sovereignty (“the prince”) with its negative projections, i.e. the victim or the figure of the excluded. The Jew, the immigrant, the rebel—are the icons of a new form of politics here. Committed to a critical thinking beyond left-right divisions or beyond Christian-Judaic separation, Agamben stresses the “threshold” as his springboard for a new critical examination of the law (in both theological and political terms). The Homo Sacer, he tells us, is the one who could be killed but not sacrificed, who exists outside both human and divine law.

Agamben’s theory of politics identifies itself as “biopolitical critique.” It criticizes racial stereotypes side by side with other forms of “total sovereignty.” However, as such, it turns not only against explicit totalitarian regimes, such as Stalin’s and Hitler’s, but against the capitalist order, which identifies life with consumption, and the realization of the self with economic profit. Both fascism and capitalism try to reach a point of total control or a “total politicization of life,” according to Agamben. From this angle, the difference between totalitarianism and democracy is one of quantity, not quality, of coercion. In this brave new world, the Homo Sacer is no longer a Jewish Muselmann, but a Muslim immigrant, an oppressed woman, or a political critic.

Law, Actually: Code and Coercion in the works of Yosef Karo

Mordechai Levy-Eichel

The Bet Yosef (completed 1542, hereafter BY) and its subsequent revision and condensation, the Shulhan Arukh (published 1564–1565, Venice, hereafter SA) of Yosef Karo are the chief legal touchstones of early modern Jewry, exemplifying the scope, and limits, of halakhic commentary and codification. Both works follow the four part division of Ya’akov ben Asher’s fourteenth century, Arba’ah Turim. The BY was published as a commentary surrounding Asher’s work, while the SA was published as a stand-alone work, including in pocket-sized editions.

Pictured here, from the Sabbioneta edition of the BY, printed in 1559, is the fourth and final part, Hoshen Mishpat, named after the high priest’s breastplate. This volume, which contains a censor’s inscription at the end, mainly treats the non-ritual aspects of leading a Jewish life (including questions of finance and sales, torts, and damages), but begins by noting how the courts should rightfully administer the law. Ironically, many of its strictures about how to follow the law—e.g., do not go before a gentile court (26:1)—exemplify ideal Jewish observance, as well as the fact that, in practice, such laws were often circumvented, excused (with or without certain halakhic qualifications), or just ignored by many, from the pious to the nefarious.

Jacob Lorberbaum’s Netivot ha-Mishpat (The Paths of Law): A Basement Encounter

Menachem Lorberbaum

Walking through the florescent lit bookshelves of library stacks is always a pretense. The book one seeks is but an excuse for a treasure hunt in the oversized shelves or the nether reaches of a certain column one has never had reason to tour before. A solitary quest in search of reverie with a hitherto imagined volume has always been the greatest of rewards since my summer job as a young lad retrieving books for callers in the basements of the Hebrew National Library in Jerusalem. The call number is one thing, the trace leading the bookworm—another.

The Katz Center Library showed great promise from the first moment; indeed as soon as I realized that I was free to roam on my own. Then came the day and my eye glanced at a folder in the oversized shelves. A closer look revealed the name Netivot Ha-Mishpat, The Paths of Law, first edition (or what is left of it) by Rabbi Jacob Lorberbaum of Lissa. I pounced upon it. I took the folder and opened it looking at the famed commentary (1809) on the part of the Sulhan Arukh devoted to civil law, Hoshen ha-Mishpat. I made my way through the leaves chancing upon a famed discussion that could have been presented by a legal scholar in our seminar on Jewish political thought, even today, on the nature of representation.

It is clear that one can represent another if appointed to do so—but can one represent another without so being appointed? The Mishnah sets forth the principle that “a person may be benefited even if not present.”

That is, one person may act on behalf of another not present if the outcome is to the latter’s benefit. The principle raises crucial questions: What constitutes a benefit? And if it involves acquisition may the latter rescind? Moreover: why? Is representation a matter of bestowing the right of action, of taking one’s place, assuming one’s power, or is a projected good enough to act on another’s behalf (even if unknowingly). Thomas Hobbes uses the term ‘personate’ to capture the representative relation. Following this insight we can continue pursuing the rabbinic train of thought. In what sense of ‘person’? In our physical capacity or our legal capacity as legal agents. Following various talumudic sources Rabbi Jacob’s discussion and the retorts of his colleagues suggest that our approach depends on the governing metaphor of representative action: is it an extension of one’s hand or of one’s competence, power?

At this point, completely lost in thought, I heard the elevator in the background—someone was coming!—and not waiting to follow the thought through I hastily put away the loose leaves in their folder and returned to the mundane respectability of the call number I originally had jotted down on my yellow sticky paper.

Abraham Ankawa: Kerem Hemer

Vered Sakal

Abraham ben Mordecai Ankawa was born in in Salé, Morocco, in 1810, to a family of Spanish origin (one of his ancestors is Ephraim Ankawa who escaped the Spanish Inquisition and, according to legend, came to the Maghreb mounted on a lion). Ankawa settled in Algeria in 1846, fourteen years after the French began their colonial conquest, and was nominated by the French authorities as a rabbin indigène in 1859. His responsa book, Kerem Ḥemer, was printed in Livorno in 1869–71. It is a collection of responsa in two volumes. The first volume is arranged according to the four parts of Shulḥan Arukh—covering most aspects of Jewish life, it discusses matters of ritual, kashruth, marriage and finance. The second volume opens with Sefer ha-Takkanot—a collection of regulations written by rabbis of Castilian origin, which Ankawa copies and publishes in order to prevent their loss. The volume also includes some of the rulings made by Rabbi Raphael Berdugo (a notable Moroccan rabbi, 1747-1821) and additional responsa from Ankawa.

It is important to note that Ankawa’s rabbinical biography and bibliography resonates strongly with the chronology of the French colonial regime in Algeria: by 1859 Ankawa and his colleagues were allowed to rule only on marital matters and religious–ritual issues. And at the time Kerem Hemer was published, the Crémieux decree had naturalized most of the Jews in Algeria and officially subordinated them to French family law, thus dissolving the last aspect of Jewish law that had some kind of jurisdictional autonomy. It seems then, that the fact that Ankawa publishes a book of responsa subsequent to the mass naturalization requires an explanation.

One option we should consider is that Ankawa publishes Kerem Hemer in order to provide Algerian halakhah with a ‘decent burial’ (if we are to utilize Scholem’s portrayal of Moritz Steinschneider’s work and all of the Wissenschaft des Judentums movement). Another possibility is to describe Kerem Hemer as an act of cultural defiance against colonial patronage that privileges certain practices or ideas over others; a demonstration of resistance to the colonial regime’s effort to marginalize local and independent Jewish ruling. In contrast with the French-colonial compartmentalizing approach, which sought to separate between politics, religion and law by setting geographical as well as clerical boundaries, Kerem Hemer should be understood as a counter religio-political project that defies colonial attempts to demolish and reconstruct indigenous religiosity.

Martin Buber’s Three Speeches on Judaism

Orr Scharf

First editions can be precious little treasures. Their tactility and physical layout are like time capsules that preserve something tangible from the moment of their production. Flipping through a first edition’s pages one is easily tempted to transport oneself to the author’s time and place and absorb the setting that inspired him or her to write a work that can still stir, perplex and invigorate our minds today. First editions are also valuable for capturing most genuinely the author’s position on the subject matter, which many times is changed or revised in subsequent editions. Martin Buber’s Drei Reden über das Judentum (Three Speeches on Judaism), a copy of whose first edition (1911) is held at the Katz Center library is such a specimen. Between the lines that moved Buber’s admiring audience in Prague, where he delivered the speeches, and thousands of subsequent readers, one may find his initial thoughts about the place of Gnosticism in the evolution of Christianity. This is probably the first text in which Buber describes the rift torn between Christianity and Judaism as having been caused by the Gnostic influences on Paul the Apostle, while Jesus’ teachings still maintained close affinities with the faith of Israel. This kernel of an idea sustained years of research and writing on the subject on Buber’s part. More than a century after its publication, Drei Reden remains a beautifully crafted book of puzzles awaiting further exploration.

Richelieu in “Marrano Garb”

Claude B. Stuczynski

The Converso poet João Pinto Delgado (Portimão 1580–Amsterdam 1653) dedicated his Poema de la Reina Ester; Lamentaciones del profeta Jeremías; Historia de Rut y varias poesías (Rouen: David du Petit Val, 1627) to Cardinal Richelieu (1585–1642). In the preface to this collection of mostly biblical verses written during his French exile, Pinto Delgado gave two reasons for offering the book to King Louis XIII’s almighty minister. On the one hand, Richelieu acted like “the most generous spirits” by protecting strangers (“amparar a los peregrinos”) like him and encouraging them to serve their hosting Princes through their military or literary skills (“unos por armas, y otros por letras”). The hospitality of the “holy Patriarchs” of the Bible was mentioned by the Converso poet as the archetype of Richelieu’s praiseworthy behavior. On the other hand, his particular way of doing politics (“de ser peregrino en todas sus acciones”) revealed that he was an outstanding minister. Knowing how to navigate the “ship” of the State like a “skilled pilot” and the army as “a wise captain”, France’s solid foundations relied on Richelieu’s virtues. Arousing fear among enemies, respect of friends and commitment of the vassals, Cardinal Richelieu was the embodiment of the perfect political leader. Employing a set of political concepts and metaphors widespread by Jean Bodin’s Les Six livres de la République (The Six Books of the Republic. 1576), Pinto Delgado saluted Richelieu for “winning that love” of the subjects vis-a-vis their sovereign “which perpetuates kingdoms.”

Pinto Delgado reminded that the books of Ester and Ruth, as well as the Lamentations of Jeremiah, showed how fragile are human beings. Living on earth as perpetual “wanderers” (“peregrinos”), the safe haven he personally found in Richelieu’s France (“allando yo un Puerto seguro, refugio de más naufragios”) along with many other Conversos exiles who fled the Iberian Inquisitions and the exclusion of the “laws of purity of blood”, deserved to be publicly acknowledged and praised. At the same time, by depicting the Cardinal Richelieu in such a way, Pinto Delgado was implicitly acting as a sophisticated Converso political thinker: showing that Richelieu’s model of combining Catholic religion, absolutistic political penchants and a minimal dose of freedom of conscience was a preferable alternative to the Iberian confessional intolerant and centrifugal model in a broader Converso phenomenon of political agency I called: “Marrano in Richelieu’s garb.”

Simone Luzzatto, Italian Humanism, and the Reason-of-State Political Tradition

Vasileios Syros

Simone Luzzatto’s Discorso circa il stato de gl’Hebrei et in particolar dimoranti nell’inclita città di Venetia (Discourse concerning the Condition of the Jews, and in Particular Those Residing in the Illustrious City of Venice) appeared in 1638, in the aftermath of allegations about Jewish involvement in the bribery of the Venetian judiciary. The work was addressed to the Venetian authorities and is one of the first political treatises written by a Jewish author in the Italian vernacular. The Discorsoadumbrates a number of themes discussed in Luzzatto’s other major work the Socrate, overo dell’humano sapere (Socrates; or, About Human Knowledge, 1651), a fictive dialogue among various ancient Greek philosophical figures on a variety of topics related to human knowledge. It attests to the author’s exposure to Italian Humanism and the Greek legacy. It also reflects Luzzatto’s deep engagement with diverse streams of early modern political thought, particularly Niccolò Machiavelli’s thinking and the reason-of-state tradition. The work is informed by Luzzatto’s concern with the foundations and features of a strong economy and the contribution of the Jewish community to Venetian trade. As such, it encapsulates a set of insights relevant to current debates on the interface of religious or ethnic diversity and economic growth.

The Politics of Library Collecting: David Oppenheim, chief rabbi of Prague (1703-1736)

Joshua Teplitsky

The volume Collectio Davidis/Qohellet David was published in 1826 in Hamburg, Germany, and was the final catalogue of a collection that had been inventoried every few decades since it was initiated in the 1670s. Behind a registry enumerating books and manuscripts in varying sizes, shapes, and paper qualities lie the activities of a collector, David Oppenheim, chief rabbi of Prague from 1703-1736. Over the course of five and a half decades, Oppenheim collected and created books and manuscripts, circulating literary material across Europe and the Mediterranean basin. He patronized the creation of new books in Hebrew and Yiddish, was visited by learned Christian Hebraists, directed philanthropy to the Land of Israel, and acted as a decisor and power-broker for Jews and their communal institutions across Central Europe.

Both as material objects and intellectual artifacts the books in this collection reveal elements of Jewish political culture: the knowledge stored in his collection was essential to the daily governance and religious lives of autonomous Jewish communities, while the motion of these objects themselves reveal the flows of favor and gift-giving—the non-institutional side of politics and administration—that were essential to the conditions of premodern Jewish collective organization.

Writers’ Words and State Building

Giddon Ticotsky

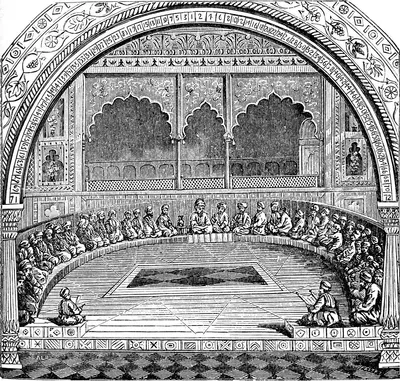

In March 1949, as the guns of the Independence War were falling silent, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion held a meeting with some forty Hebrew authors, poets and intellectuals to discuss the shaping of the young state’s spiritual image, as well as the absorption of the huge immigration waves and other fundamental issues. This meeting was followed by another one, held in October 1949.

Detailed minutes of the two meetings were published by the Government Printer, shortly after each meeting, titled Divrei Sofrim (Writers’ Words: alluding to biblical scribes or adjudicators). These two booklets document an ideologically charged encounter between the Hebrew Republic of Letters and the nascent state. At the same time they shed light on the key role Hebrew authors used to have—and may still have today—in Israeli society, perhaps much more than their counterparts in other Western societies.

Ben Gurion’s Dedication

Giddon Ticotsky

The Library at the Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies holds a rare copy of Ben-Gurion’s collected essays, Hazon ve-derekh (Vision and a Path) with his dedication to his wife. It reads as follows (in English translation): “To Paula, with love, ‘I remember the devotion of your youth, your love as a bride, how you followed me in the wilderness, in a land not sown’ – David.” The verse from Jeremiah (2:2, English Standard Version) probably refers to the Ben-Gurion family’s move to the wilderness of the Negev desert in southern Israel, after he resigned from his position in 1953. The fifth volume of his essays, which carries this dedication, was published in 1957, two years after he became Prime Minister again.

Hospitals as Instruments of Politics

Irene Tucker

Two recent, highly acclaimed Israeli novels, David Grossman’s Ishah borahat mi-besorah (Woman Flees from the News/To the End of the Land) and Ayelet Gundar-Goshen’s Le-hair aryot (Waking Lions) represent hospitals as institutions uniquely capable of serving the diverse population of contemporary Israel and environs. In these accounts, hospitals—some of them operating underground, in remote basements or overlooked garages in the middle of the Negev, others in plain sight on expansive urban campuses—offer care to Jewish Israelis, Palestinian citizens and non-citizens of Israel, guest workers and refugees from the Philippines and central Africa, without regard to their political status, their capacity to pay, or even their social legibility. Where political institutions and the culture at large might fail in their aspiration to treat all people as deserving of equal access to resources and legal protections, hospitals make such equal access their operating credo. In these novels, hospitals function as a sort of state beyond politics.

In fact, far from functioning outside politics, from the middle of the nineteenth-century onward, hospitals in the Middle East were central instruments for creating a political presence where none had existed. Because English Protestant missionaries lacked the status of “keepers of Christian Holy Places” granted the Catholic, Armenian and Greek Orthodox Churches, they were not allowed to settle in Palestine under the Ottoman Empire. As Yaron Perry and Ephraim Lev document in their 2007 Modern Medicine in the Holy Land: Pioneering British Medical Services in Late Ottoman Palestine, a missionary organization known as “The London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews,” used the occasion of a protracted military clash between Egyptian Governor Muhammed Ali and the military forces of the Ottoman Empire during the 1830s to gain a foothold in Jerusalem. By founding a hospital that would offer treatment to the many residents of Palestine vulnerable to malaria and other sicknesses endemic to the region, the London Jews Society imagined that they might establish a presence Muslim, Jewish and Christian residents of Jerusalem would regard with gratitude, rather than see as an incursion. It was the establishment of this hospital (pictured at left) and many other missionary-run hospitals like it that paved the wave for the British presence in fin de siècle Palestine that culminated in the recognition of postwar British Mandate.

Selected Bibliography

-

Ackerman, John. The Politics of Political Theology: Rosenzweig, Schmitt, Arendt [dissertation]. Chicago, Northwestern University, 2013.

-

Ben Shitrit, Lihi. Righteous Transgressions: Women’s Activism on the Israeli and Palestinian Religious Right. under contract, Princeton University Press.

-

Brody, Samuel. This Pathless Hour: Messianism, Anarchism, Zionism, and Martin Buber’s Theopolitics Reconsidered [dissertation]. Chicago, University of Chicago, 2013.

-

Cooper, Julie. Secular Powers: Humility in Modern Political Thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

-

Dubin, Lois C. The Port Jews of Habsburg Trieste: Absolutist Politics and Enlightenment Culture. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999.

-

Edrei, Arye. “From Orthodoxy to Religious Zionism: Rabbi Kook and the Sabbatical Year Polemic,” in Dine Israel: Studies in Halakhah and Jewish Law )26-27 (2009-2010), 45-145).

-

Gur, Golan. Orakelnde Musik: Schoenberg, der Fortschritt und die Avantgarde. Kassel: Baerenreiter 2013.

-

Jobani, Yuval and Perez, Nahshon. Women of the Wall: Navigating Religion in Sacred Sites. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

-

Jones, Meirav; Oz-Salzberger; Fania; Schochet, Gordon, eds. Political Hebraism: Judaic Sources in Early Modern Political Thought. [Israel] Shalem Press, 2008.

-

Kobrin, Rebecca A. Jewish Bialystok and Its Diaspora. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

-

Lebovic, Nitzan. The Philosophy of Life and Death: Ludwig Klages and the Rise of a Nazi Biopolitics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

-

Levy-Eichel, Mordechai. “Into the Mathematical Ocean: Navigation, Education, and the Expansion of Numeracy in Early Modern England and the Atlantic World,”, [dissertation] (New Haven: Yale University, 2015).

-

Lorberbaum, Mordechai. Politics and the Limits of Law: Secularizing the Political in Medieval Jewish Thought. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002.

-

Sakal, Vered. “Two Conceptions of Religious Self in Lockean Religiosity,” in The Journal of Religion (96, 3 (July 2016): 332-345).

-

Scharf, Orr. Thinking in Translation: Scripture and Redemption in the Thought of Franz Rosenzweig. New York: W. De Gruyter, 2018.

-

Stuczynski, Claude B. “Harmonizing Identities: the Problem of the Integration of the Portuguese Conversos in Early Modern Iberian Corporate Polities,” in J_ewish History_ (25, 2 (May 2011): 229-257).

-

Syros, Vasileios. Marsilius of Padua at the Intersection of Ancient and Medieval Traditions of Political Thought. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012.

-

Teplitsky, Joshua. “A ‘Prince of the Land of Israel’ in Prague: Jewish Philanthropy, Patronage, and Power in Early Modern Europe and Beyond,” in Jewish History (29, 3-4 (December 2015), 245-271).

-

Ticotsky, Giddon, ed.. Lea Goldberg-Tuvia Ribner: Correspondence. Bene Berak: Sifriyat Po’alim; ha-Kibuts ha-me’uhad, 2016.

-

Tucker, Irene. The Moment of Racial Sight: A History. Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Contributors

-

John Ackerman - University of Kent / Jody Ellant and Howard Reiter Family Fellowship

-

Samuel Brody - University of Kansas / Albert J. Wood Fellowship

-

Julie Cooper - Tel Aviv University / Robert Carrady Fellowship

-

Lois Dubin - Smith College / Ellie and Herbert D. Katz Distinguished Fellowship

-

Golan Gur - University of Cambridge / Dalck & Rose Feith Family Fellowship

-

Yuval Jobani - Tel Aviv University / Louis Apfelbaum and Hortense Braunstein Apfelbaum Fellowship

-

Meirav Jones - Yale University / Charles W. & Sally Rothfeld Fellowship

-

Rebecca Kobrin - Columbia University / Ella Darivoff Fellowship

-

Nitzan Lebovic - Lehigh University / Ruth Meltzer Fellowship

-

Mordechai Levy-Eichel - Princeton University / Ruth Meltzer Fellowship

-

Menachem Lorberbaum - Tel Aviv University / Ellie and Herbert D. Katz Distinguished Fellowship, Erika A. Strauss Teaching Fellowship

-

Vered Sakal - Tel Aviv University / Jody Ellant and Howard Reiter Family Fellowship

-

Orr Scharf - The Open University of Israel / Ruth Meltzer Fellowship

-

Claude B. Stuczynski - Bar-Ilan University / Nancy S. & Laurence E. Glick Teaching Fellowship, Primo Levi Fellowship, Rose & Henry Zifkin Teaching Fellowship

-

Vasileios Syros - Academy of Finland / Maurice Amado Foundation Fellowship

-

Joshua Teplitsky - Stony Brook University / Ruth Meltzer Fellowship

-

Giddon Ticotsky (Writers’ words | Ben Gurion) - Stanford University / Ruth Meltzer Fellowship

-

Irene Tucker - University of California, Irvine / Maurice Amado Foundation Fellowship

Special thanks

Special thanks above all to Leslie Vallhonrat, the Penn Libraries’ peerless Web Unit manager for designing this web exhibit and for meticulously reviewing every detail, to Bruce Nielsen and Josef Gulka at the Library at the Katz Center, as well as to Eri Mizukane and Thomas Hensle at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscript and Michael Overgard and the staff at the Schoenberg Center for Text and Image (SCETI) for their time and unflagging efforts coordinating the digitization of images for this exhibition.