13th Century Entanglements: Judaism, Christianity & Islam

Introduction

The 2012-13 fellowship year at the Katz Center brought together scholars of Jewish, Christian, and Islamic social and intellectual history to develop a more fully integrated account of Europe and the Mediterranean basin in the 13th century. Diverse phenomena such as the creation of new philosophic and scientific cultures, the emergence of medieval halakhah (Jewish legal praxis), the diffusion of Kabbalah, the establishment of new mendicant orders, the institutionalization of Sufi brotherhoods, the rise of universities, and the role of inquisitors were studied, not only as isolated phenomena but in their mutual interrelations. In this on-line exhibition we highlight a number of original sources that were draw upon by these scholars in the course of their research: Hebrew, Latin and Arabic manuscripts and early printed texts which illustrate a range of topics such as medieval liturgical poetry, law, rhetoric, philosophy, science, magic, social history, gender relations, inter-communal contact, conflict and other forms of entanglement both positive and negative.

Exhibition cover design adapted from a decorative incipit and illuminated motifs found in a 13th-century Latin translation of an Arabic medical treatise by a 9th/10th-century Jewish physician (Isaac Israeli/Abu Ya’qub Ishaq ibn Suleiman al-Isra’ili)) to the Fatimid Caliph Ubaid Allah al-Mahdi (909-34) in Qairawan (found in present-day Tunisia). The original codex, a miscellany of the fundamental medical textbooks of thirteenth-century Paris, is found in the Lawrence J. Schoenberg Collection at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries, manuscript 24 (decorative elements on folio 51 verso, 52 recto and elsewhere). Design credit: Leslie Vallhonrat.

Exhibit

Liturgical poetry from Ashkenaz

Elisabeth Hollender

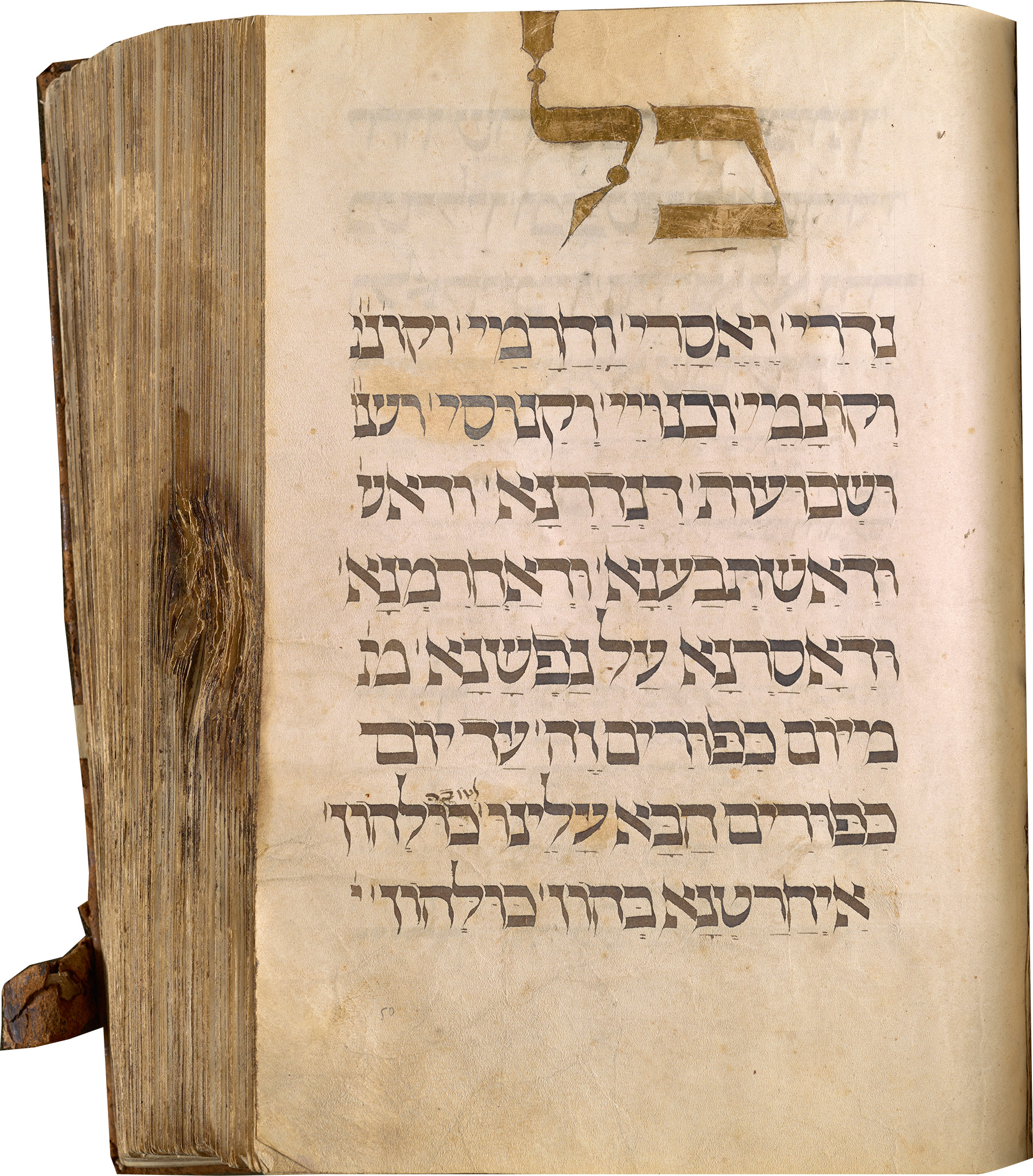

Rare ms. 382 in the collection of the Library at the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies is a mahzor (festive prayerbook) for the autumn holidays according to the Western Ashkenazic rite. It was copied during the fourteenth century, probably in the Rhineland area of southern Germany and northern Italy. It contains the liturgical poetry (_piyyutim_) recited in the synagogue on both days of Rosh ha-shanah, on Yom Kippur, on the first and second day of Sukkot, the intermediate Sabbath during Sukkot and on Shemini Atseret, but it lacks most of the standard prayers said on these occasions because the precentor would have known these by heart. Today, the volume is incomplete, beginning with musaf (the additional prayers) recited on the first day of Rosh ha-shanah and ending with musaf on Shemini Atseret. In its complete form it would have contained more than 280 folio leaves (rather than the extant 252 folios). In addition to at least two quires missing at the beginning and one quire missing at the end, several pages have been cut out of the manuscript. The manuscript was rebound in (early) modern times and apparently after that was damaged, probably by fire.

During the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, several changes took place in the production of liturgical manuscripts in Ashkenaz that influenced both the selection of texts and the appearance of the texts on the page. Notwithstanding unifying tendencies, many communities retained their local traditions about which piyyutim to say when, as mirrored by the unusual ordering of yotsrot for Sukkot in the Katz Center’s mahzor. Most textual changes that spread throughout many communities pertain to the omission of piyyutim, e.g. many communities decided to abbreviate the recitation of qedushta’ot, the complex compositions adorning the Amidah on Sabbaths and holidays, by skipping parts of the rehitim, the series of highly structured poems in the penultimate position of the qedushta, especially on the high holidays when many piyyutim were recited. The mahzor of the Katz Center displays a selection that is largely in accordance with later habits, although in one case a piyyut that had been omitted by the original scribe was added on the margins by an almost contemporary hand (f. 143r). This note was preserved when the margins were cut at a later time, suggesting that the community using the mahzor continued to recite this piyyut. Interestingly, the mahzor does not share another textual change of the late thirteenth, early fourteenth century, namely the omission of the strings of verses inserted into the first three piyyutim of qedushta’ot, although it rarely contains more than three or four verses, even though earlier manuscripts may have up to seven or eight verses in each string.

Among the piyyutim retained by the original scribe were two anti-Christian piyyutim in the rehitim for shaharit on Yom Kippur that would have appealed to the Jewish communities in Ashkenaz in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries who could use the liturgy to express their antagonism to Christianity in times of growing tension, but apparently these piyyutim were considered to be superfluous or even dangerous at a later time, when the leafs containing this piyyutim were cut from the mahzor (f. 105 and 108). Only one occasion of the Aleynu is censored (by erasure) while another occasion of the same text was not changed. It is not possible to reconstruct when this drastic measure was taken, nor whether it is a case of self-censure or due only to outside pressure. Cutting out the piyyutim was eased by the selective recitation of rehitim that began in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and had led to the omission of some rehitim from the manuscript.

The aesthetic changes in the visual appearance of liturgical manuscripts in Ashkenaz developed during the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. Changes in parchment manufacturing brought about a more generous layout with lavish margins, ample space between the lines, sumptuous initial words and—by the end of the thirteenth century—intricate visualizations of poetic structures like acrostics, stanzas, hemistichs and recurring elements. The Katz Center’s mahzor displays most of these, although the margins were cut by approximately 1.8 inches on one side, probably by a little less on the other sides, when the volume was rebound in (early) modern times, changing the appearance of the page dramatically, even though the layout is still generous. Some liturgical manuscripts from the fourteenth century use color to mark structure in poetic texts, e.g. for acrostics or biblical verses at the end of stanzas. The mahzor of the Katz Center uses black ink only, with the exception of some dots around the letters of initial words in the Hosha’anot section and the same red ink in the decoration of the beginning of this section. The scribe took however great care to create well-structured and diversified pages with marked acrostics and poetic structures, using larger letters and short lines, sometimes creating the impression of columns of text. He enlarged the initial words of all piyyutim and created major word initials for the complex compositions. The tradition to pay special attention to the beginning pages of yotsrot is attested in Ashkenazic mahzorim since the early thirteenth century, and it seems to have guided the scribe of this mahzor: The initial word of the yotser for the second day of Rosh ha-shanah is framed in a decorated panel, the initial word of the kol nidre is gilded. Other pages they might have contained decorated panels at the beginnings of other yotsrot are missing (first day of Rosh ha-shanah at the beginning) or were cut from the manuscript (second day of Sukkot, Shemini Atseret). The initial word of the yotser for the intermediate Sabbath of Sukkot (f. 210r) is peculiar in that a decorated panel was cut from the page and a parchment patch was inserted, reconstructing the text on both sides of the patch in a later but careful hand. Even though the manuscript does not contain illustrations, which can be found in many contemporary mahzorim, but used geometrical designs to decorate the panels for the initial words, it is likely that the missing pages from the beginning of yotsrot were cut out in order to be collected or displayed as examples of beautiful medieval manuscripts.

Rabbi Isaac ben Moses and his Sefer Or Zaru’a

Ephraim Kanarfogel

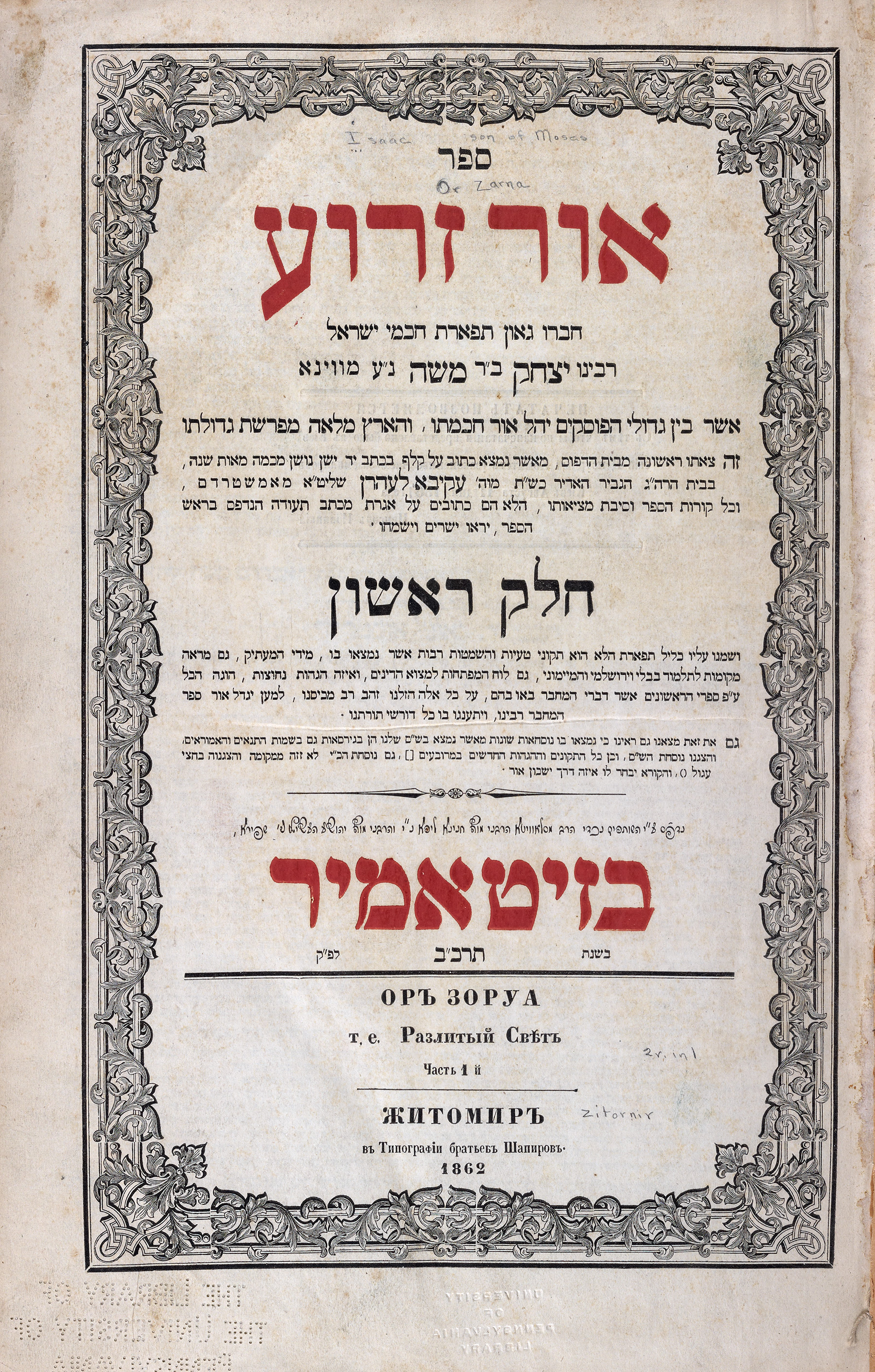

Rabbi Isaac b. Moses (d. c. 1250) appears to have hailed from Bohemia. He studied in both Germany and northern France with a bevy of the leading Tosafist glossators of his day, including Simhah ben Samuel of Speyer, Eliezer b. Joel (Rabiah) ha-Levi of Cologne, Judah b. Isaac Sirleon of Paris, and Samson of Coucy, and he also studied with the founder of the German Pietists, Judah b. Samuel the Pious. The geographic diversity of Isaac’s teachers, which renewed a trend that dated from the mid-twelfth century in Ashkenazic lands but had become attenuated for a period of about forty years (c. 1175-1215), gave Isaac access to both the German and north French centers of Tosafist endeavors, and to a rich array of their writings in the fields of talmudic commentary and Jewish law.

Not surprisingly, Isaac’s magnum opus, Sefer Or Zaru’a, is a large and discursive work that covers a wide range of legal topics. The sheer size of the work caused Isaac’s son, Hayyim, to comprise a rather drastic abridgement, and also helps to explain the seeming unavailability of this work for a period of close to 400 years, until the first phase of its publication in Zhitomir in 1862.

Isaac was a careful recorder of his teachers’ rulings and religious practices, and of the challenges that they and their predecessors faced in their respective communities. Isaac mentions in passing the forms or ornaments that had to be displayed on one’s clothing—as mandated by the Christian authorities—even on the Sabbath, which he observed during his student days in northern France. This is perhaps one of the earliest references to Jews actually wearing the badge that had been mandated by the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215.

Bonds of Friendship: A Shared Biblical Tradition

Ruth Karras

David and Jonathan were the paradigm of male friendship in both the Christian and Jewish Middle Ages. Their bond was understood in both traditions as following in the classical pattern of friendships, especially in a military context, between an older and a younger man, and by the later Middle Ages in both Christian and Jewish culture took on the trappings of chivalry. The story was retold in prose and verse, in Latin and a variety of medieval vernaculars, including Yiddish, and Christian and Jewish biblical commentators used it to make a variety of points, only some of which related to the nature of male friendship.

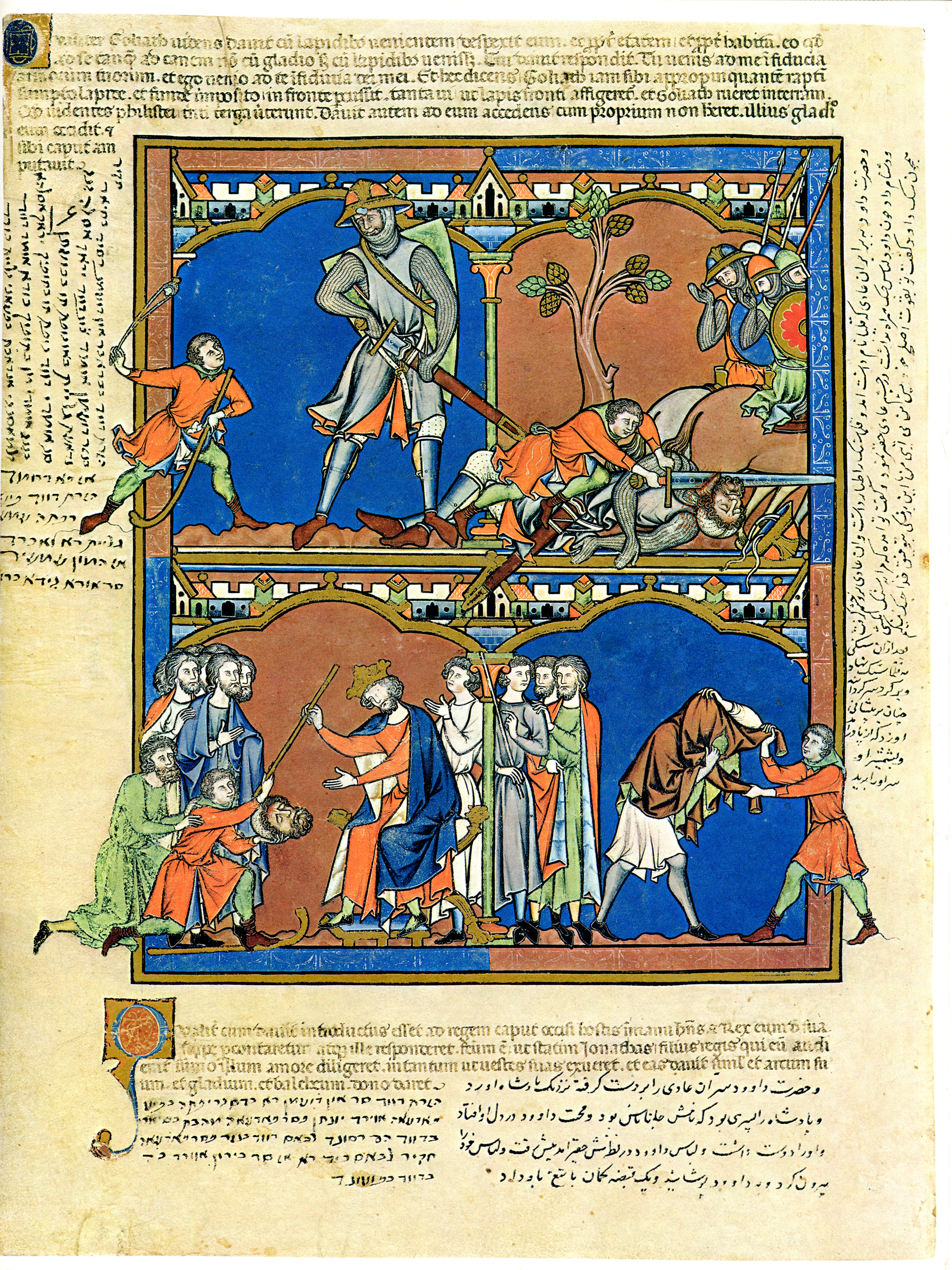

In a magnificent thirteenth-century book of Bible illustrations mostly contained in Morgan Library MS 638, folio 28 verso, we find this illustration of 1 Samuel 17 and 18. David, as a youth, killed Goliath, and Jonathan, the son of King Saul, was so taken with him that he “loved him as himself” and they made a covenant, after which Jonathan gave David his cloak, weapons and sword-belt.

The book was made in France around the middle of the thirteenth century, with the Latin text added during the subsequent century. In 1608 the book was given as a gift to Shah Abbas, who had the Latin text translated into Persian; later, text in Judeo-Persian was added.

A Hebrew Christian Calendar

Elisheva Baumgarten

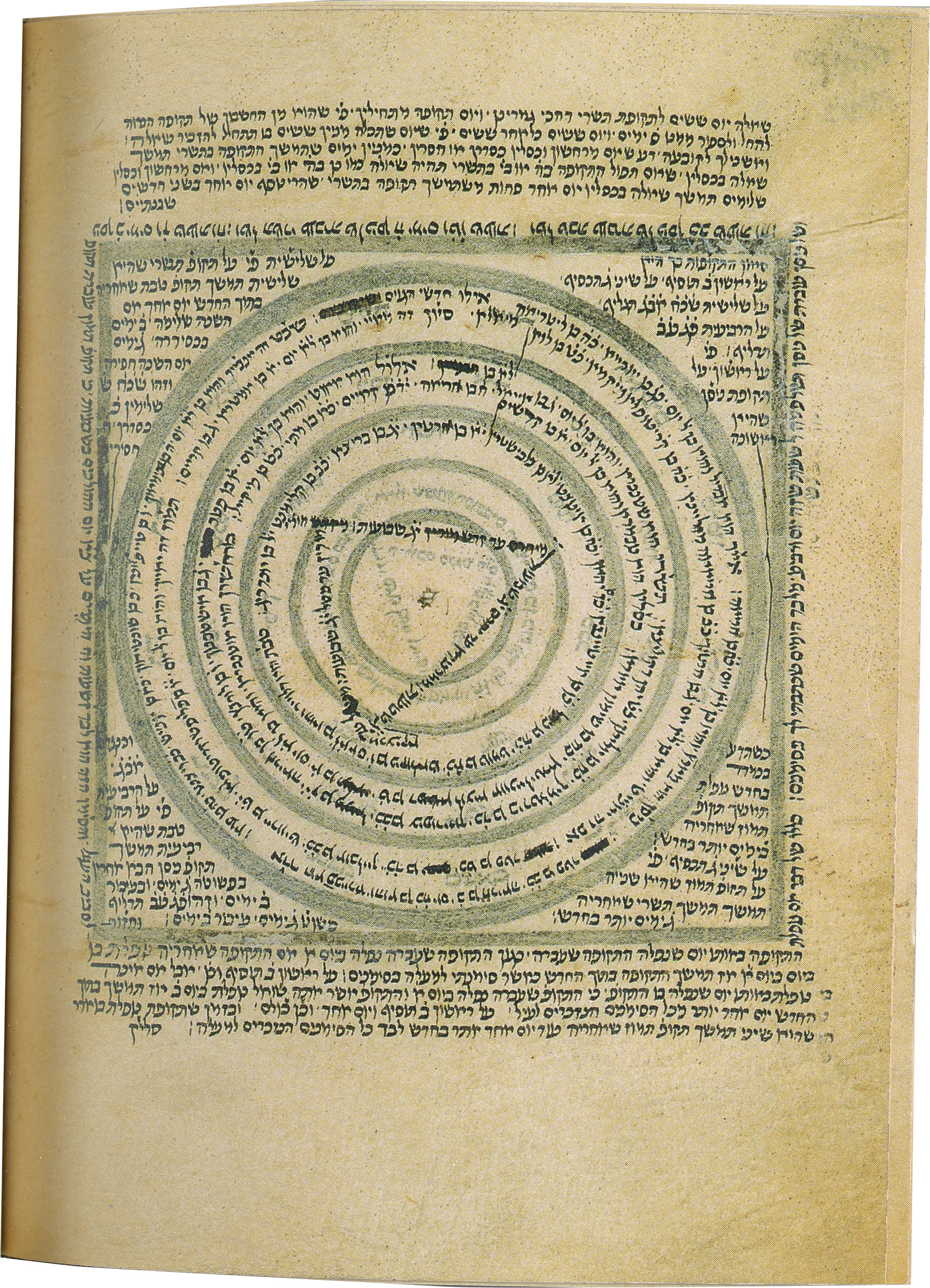

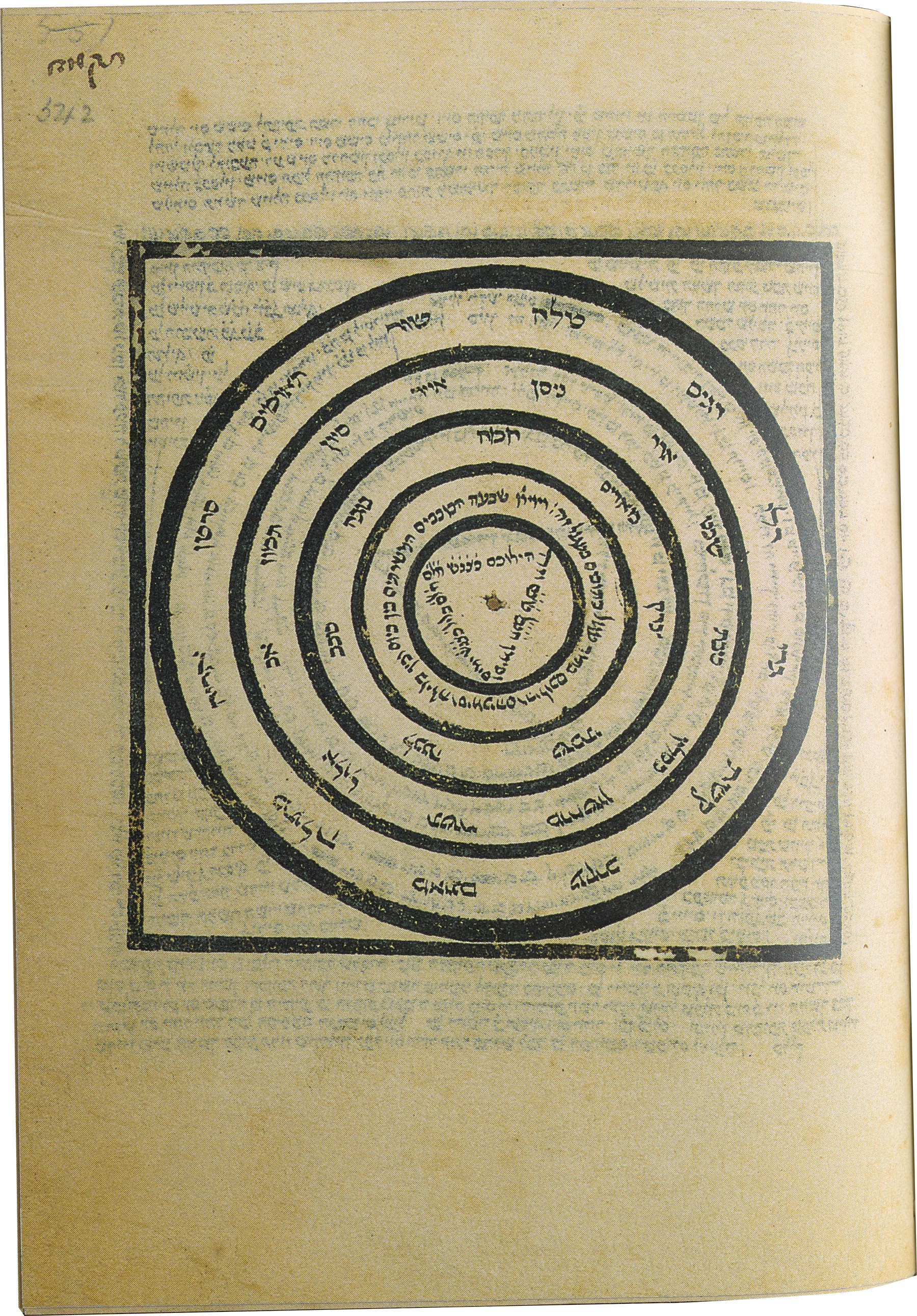

This late thirteenth-century Hebrew volume, known as the Northern French Hebrew Miscellany (Falter Facsimile Editions; British Library 11639), is among the most beautiful extant illuminated Hebrew manuscripts copied by a man noted in the colophon as Benjamin the Scribe. As in many medieval Hebrew liturgical compendia, this collection includes numerous Jewish calendric computations as well as a complex diagram of the signs of the zodiac.

Guided by the zodiac, a Christian calendar written in Hebrew, one of the earliest such calendar known to date, was inserted towards the end of the manuscript (fol. 542v). Each of the four corners of this page provides instructions for calculating the equinox or solstice times, standard components of Jewish calendars that in most Hebrew manuscripts are not linked to the Christian calendar. The inner triangle records the annual ecclesiastic calendar, detailing its four 13-week periods, reflecting its four-part economic division of the year. The concentric circles that surround the triangle outlined the different saints’ days celebrated by the Christians. These are evidence of the intimate acquaintance medieval Jews had with the Christian ritual cycle and with the importance of this knowledge that provided guidelines for business and social relations.

Sefer ha-Temunah

Ehud Krinis

Pictured here is the front page of the Lemberg 1892 edition of Sefer ha-Temunah (the Book of the Image). This anonymous work is considered a classical exposition of the Kabbalistic world cycles doctrine (Hebrew: Torat ha-Shemitot). Gershom Scholem, in his groundbreaking studies on the origins of the Kabbalah, considered this text to be a product of the Gerona circle, the earliest Kabbalistic circle in Spain, whose activities are traced to the first half of the thirteenth century. Late in his life Scholem acknowledged that his conclusions about the date and the historical circumstances of Sefer ha-Temunah are unsustainable. Subsequent studies carried by Efraim Gottlieb and especially by Moshe Idel suggested that Sefer ha-Temunah was written well into the Fourteenth century by a Kabbalist who most probably lived outside Spain. The reassessment concerning of the time and the place of Sefer ha-Temunah open the door for a new understanding regarding the development of the world cycles doctrine in early Kabbalah. Rather than emerging suddenly, it seems now that the world cycles doctrine was developing gradually, from its concise formulations in writings of the Gerona circle of Kabbalists of the first half of the thirteenth century, to the elaborate expositions of works such as Ma’arekhet ha-Elohut (_The Divine System_) and Sefer ha-Temunah, about a century later.

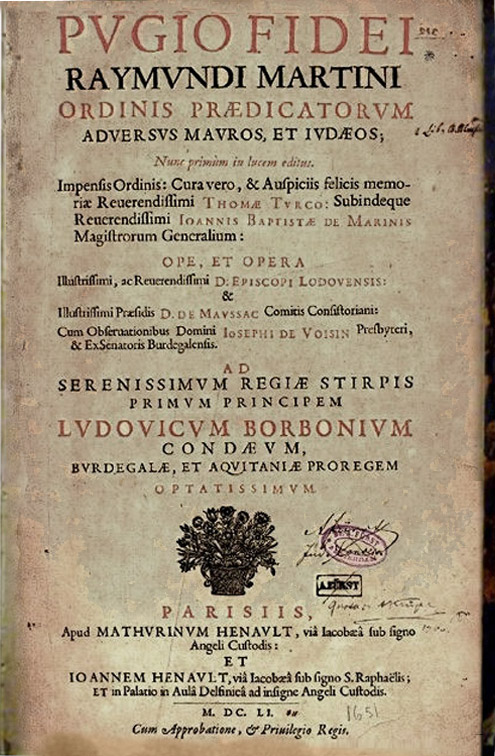

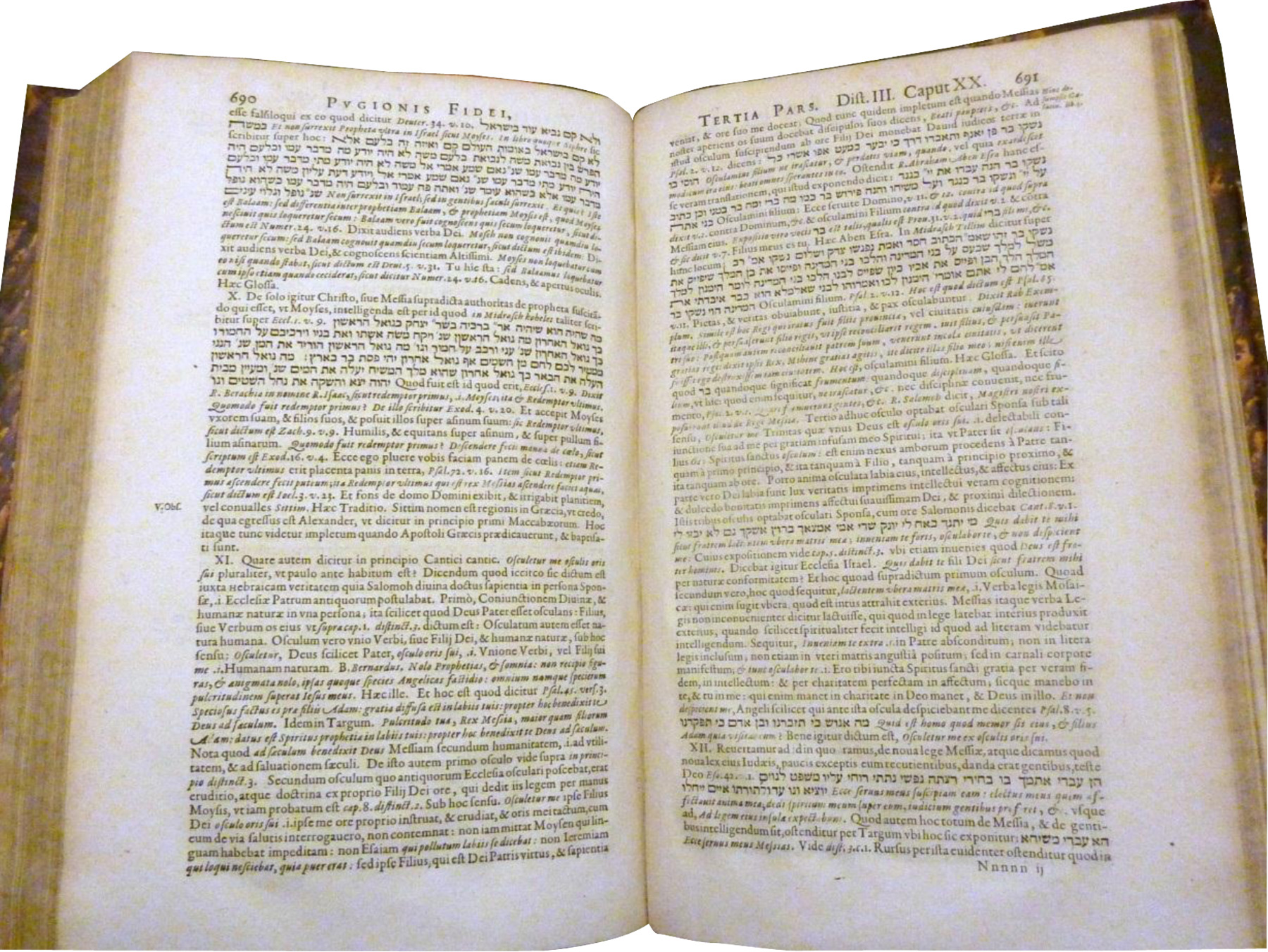

The reception of Raymond Martí’s Pugio fidei in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries

Alexander Fidora

The Pentateuch Commentary of Moses Nahmanides

Mordechai Z. Cohen

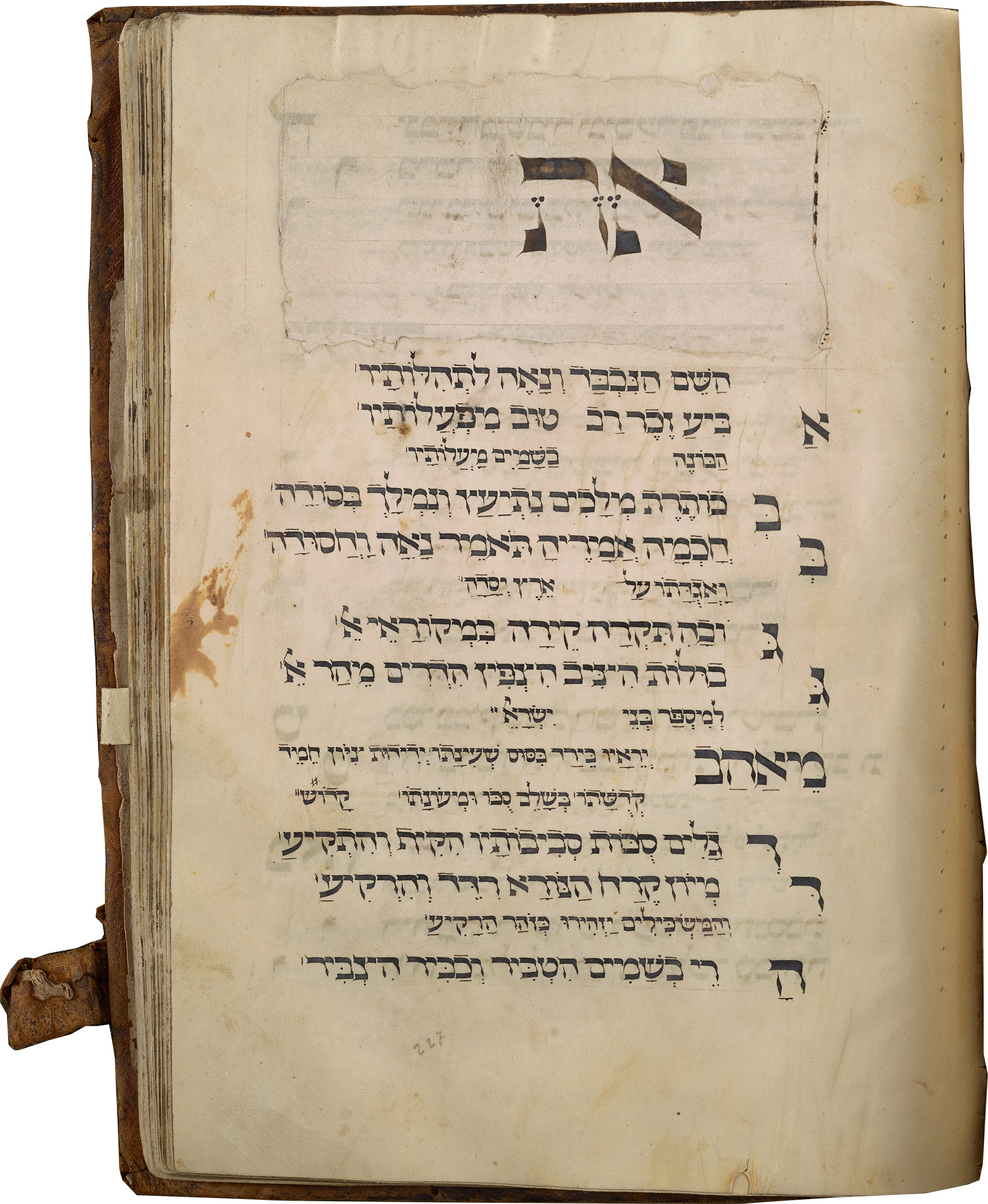

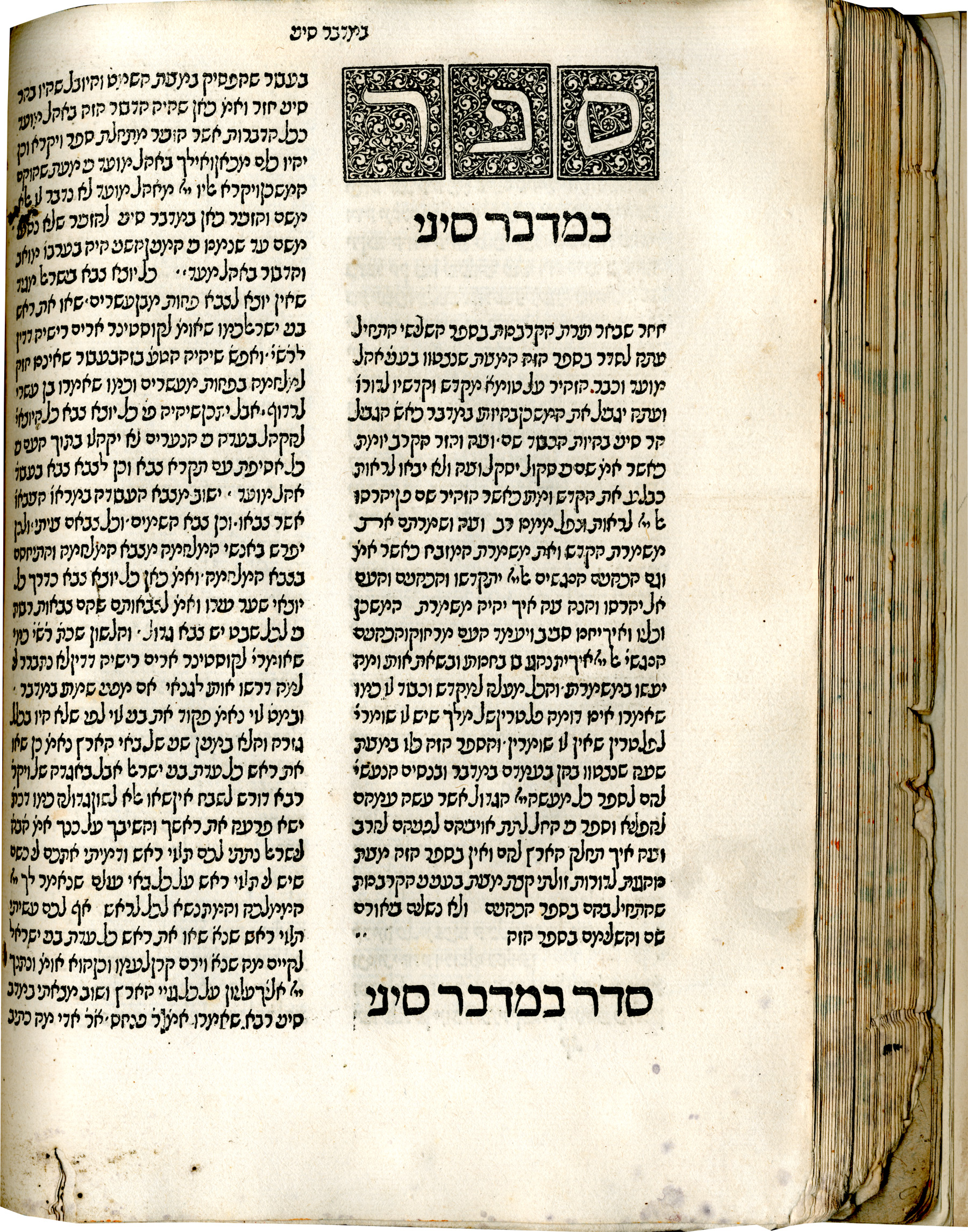

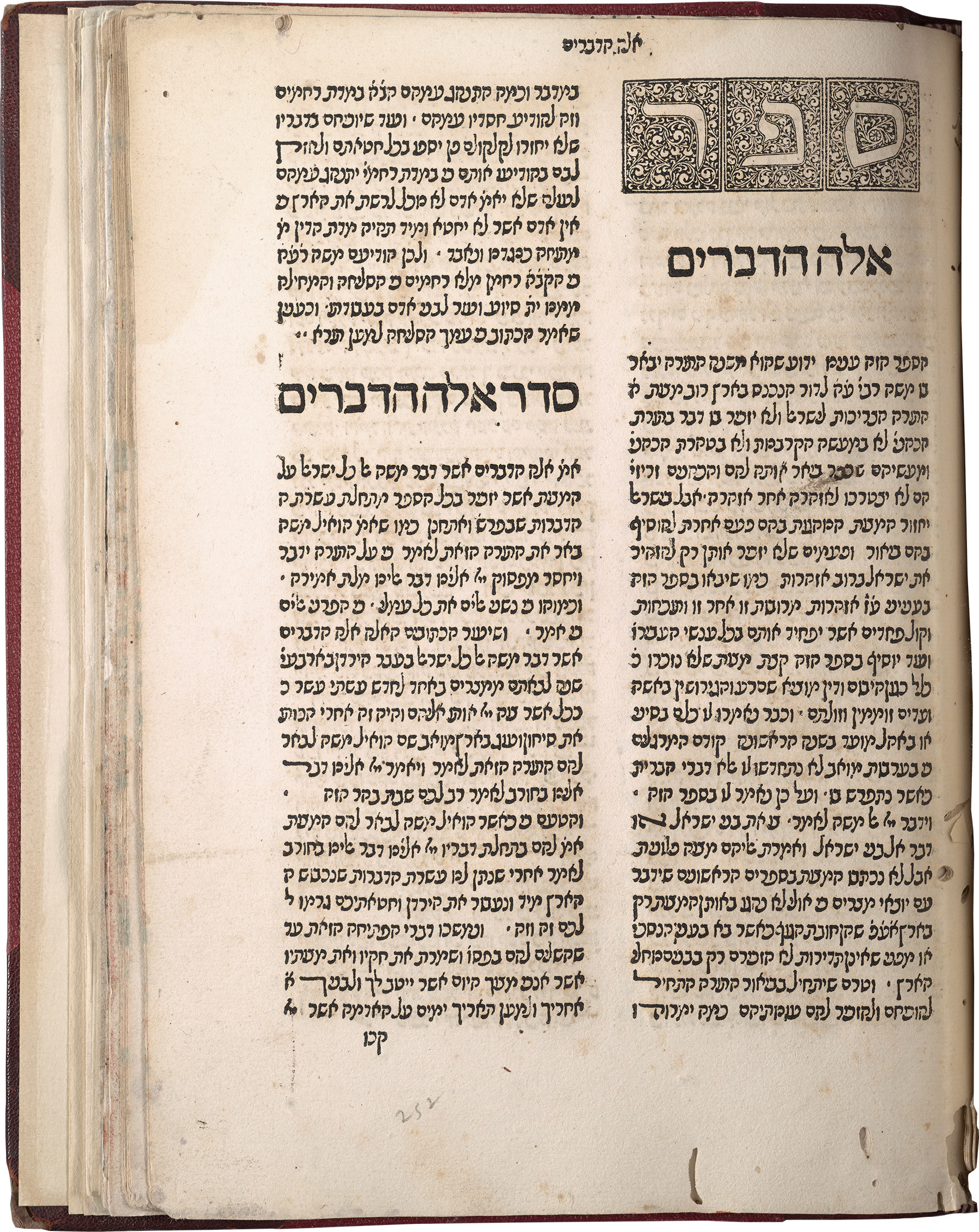

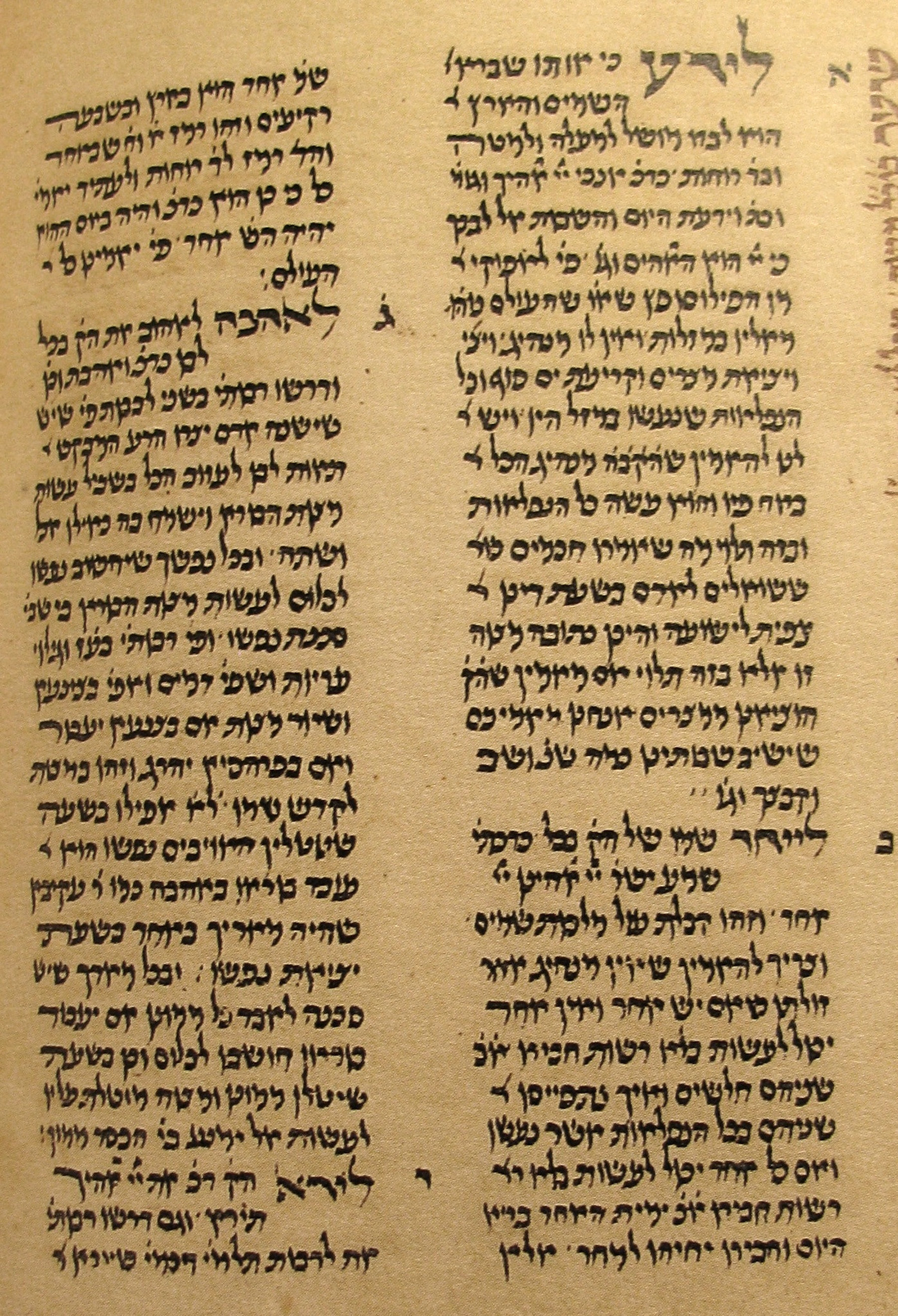

Displayed here are two pages from the Pentateuch commentary of Moses Nahmanides (1194-1270), the great Catalan exegete, talmudist, and kabbalist. As reflected in this commentary, Nahmanides stood at an intellectual crossroads of multiple interpretive traditions that he inherited in partial and refracted ways. On the one hand, he was heir to the Geonic-Andalusian school, which migrated into Christian Spain as the Reconquista progressed. Although Nahmanides evidently did not read Arabic, he avidly absorbed a mediated version of Geonic and Andalusian learning in the Hebrew writings of Abraham Ibn Ezra and David Kimhi, as well as the recently composed Hebrew translations - by Judah and Samuel Ibn Tibbon and Judah Alharizi - of works by Saadia, Ibn Janah and Maimonides. At the same time, Nahmanides was influenced by the momentous innovations in talmudic learning in twelfth-century northern France, which was accompanied by a deep respect for Rashi and his Bible commentaries. On the other hand, Nahmanides largely ignores - or perhaps was unaware of - the refined peshat commentaries of Rashi’s students, the great pashtanim Joseph Qara and Rashbam.

There is a distinctive theological strain in Nahmanides’ Pentateuch commentary. He incorporates - but at times engaged in - a polemic with the philosophical interpretive mode of Moses Maimonides, as expressed in the latter’s Guide of the Perplexed. As a counterbalance to Maimonides’ rationalistic outlook, Nahmanides often presents a kabbalistic reading of the biblical text, finding within it deep mystical meanings. He avers, for example, that the entire Pentateuch can be read as a secret amalgam of divine names, in addition to its reading “according to the commandments” i.e., in its literal sense as the Law. It is the literal sense, or peshat, that leads Nahmanides to note structural and other literary features of the Pentateuch. The two pages displayed here are from his introductory remarks to Numbers and Deuteronomy, in which he endeavors to identify the distinctive themes of these two books of the Pentateuch - as he does for Genesis, Exodus and Leviticus - thereby providing a rationale for its five-part literary organization.

Although he his one among many Jewish authors over the centuries who have interpreted the Bible, Nahmanides’ multi-dimensional Pentateuch commentary is considered among the most profound, and is avidly studied to this day.

Becoming Tosafot

Rami Reiner

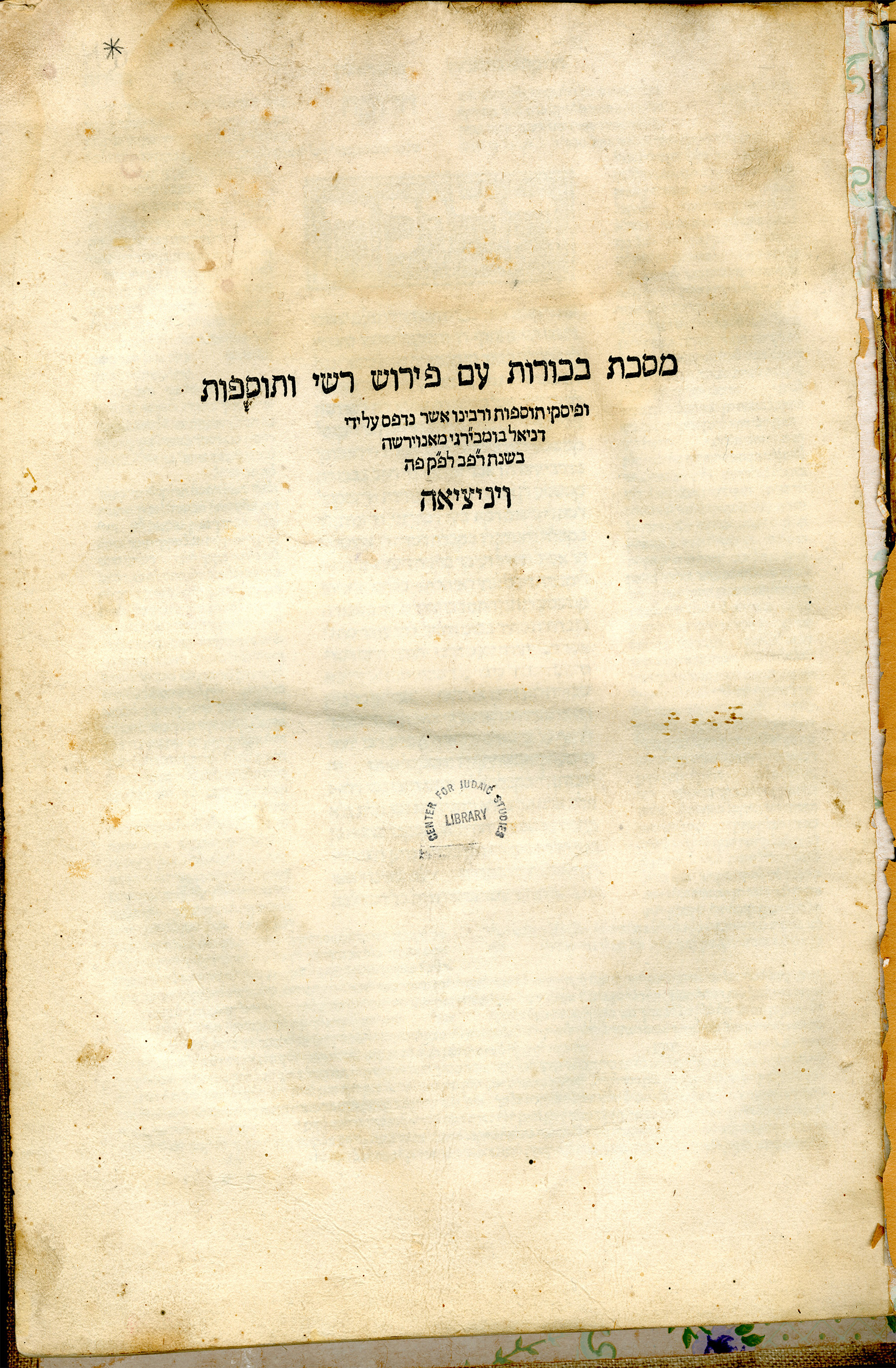

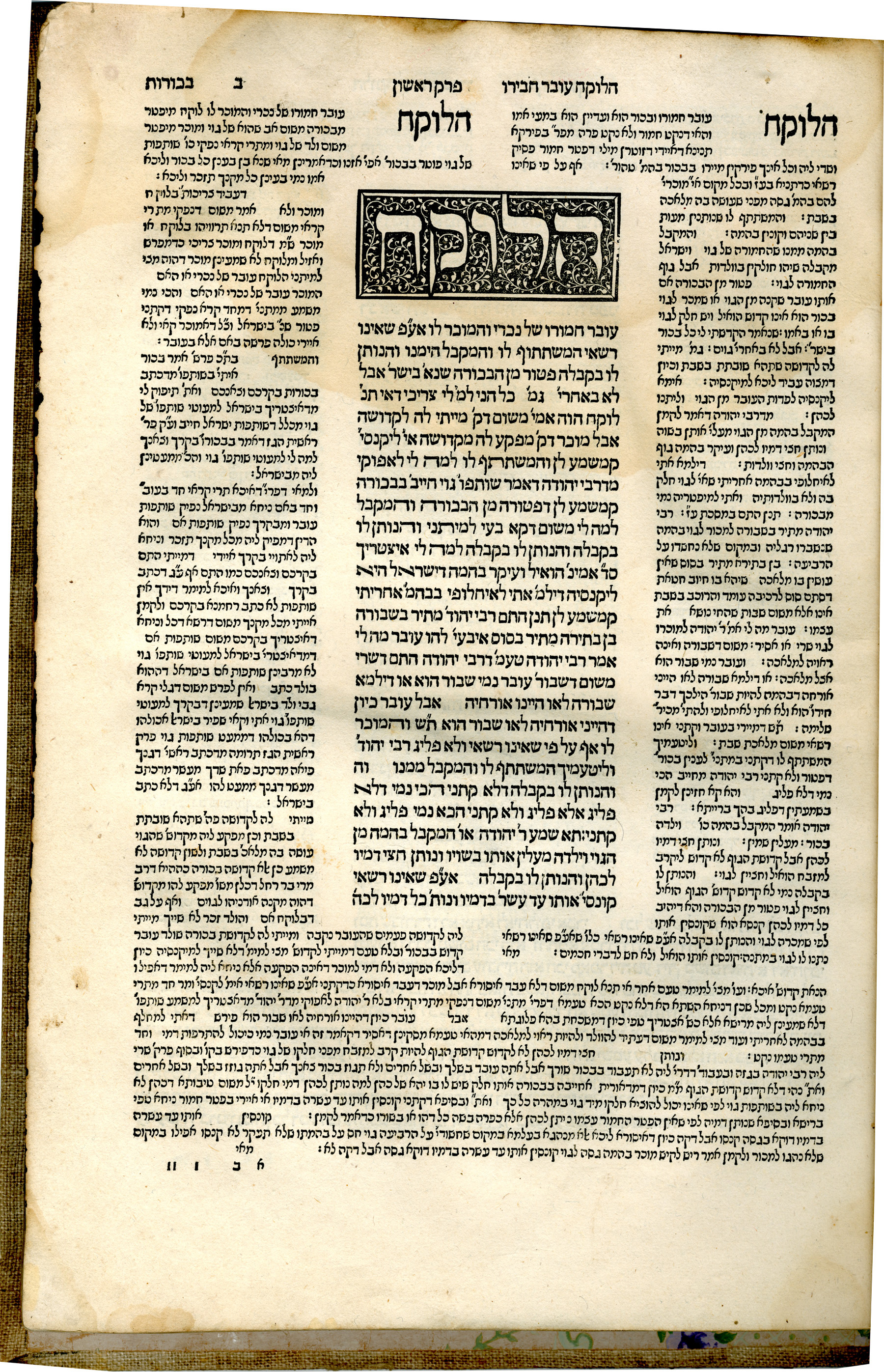

The copy of Tractate Bekhorot included in this exhibition is one of the volumes of the first complete edition of the Talmud, printed in the printing house of Daniel Bomberg in Venice between 1520 and 1523. Bomberg’s edition had a huge impact on the use and study of the Talmud. The page layout introduced in the Venice printing has been preserved in virtually every subsequent printing of the Talmud, including the famous Vilna edition and the recent Schottenstein edition. This is no accident. The advent of printing changed the way in which citations to the Talmud are given. During the manuscript era, scholars would refer to a specific Talmudic discussion by its name and the name of the chapter in which it appeared. After the printed editions took hold, it became possible to give a much more precise reference to the page within the tractate on which the source appeared. The popularity and wide distribution of the Bomberg edition led its page numbers to become the universal standard.

The significance of the Venice printing is not only in the text of the Talmud, but also in what it added to the Talmud which would with time become an integral part of the text—Rashi’s commentary, printed on the inner margin of every page, and the comments of the Tosafot, French sages from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, on the outer margin. One can hardly overstate the role played by the Venice Talmud, which combined these elements on a single page, in creating the form of study known as GaPaT—Gemara (Talmud), Rashi and Tosafot. GaPaT became the classic form of Talmud study for centuries, to this very day. The innovation of having the commentaries of Rashi and Tosafot on the same page as the Talmud meant that one need not open more than one book at a time to study the Talmud. This led to a decline in the use of manuscript versions of Tosafot commentaries, and far fewer such manuscripts have survived to the present day than medieval manuscripts in other genres. The ease of studying a printed, glossed text overpowered the conservative urge to preserve old study habits and old books, and led to the disappearance of other Tosafot collections.

Finally, the layout of the printed page of the Talmud could be considered a further chapter in a thread of Jewish history which began with the Mishnah edited by Rabbi Judah the Patriarch in the Galilee in the third century, and continued with the Talmud itself which was created in Babylonia from the third to the fifth centuries. Rashi’s commentaries were written in the eleventh century in the Franco-Ashkenazic cultural sphere, since Rashi himelf was born in France and educated in the academies of Germany. The Tosafot were written in that same area, principally during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Thus, the printed Talmud page brings together multiple generations of the Jewish people who in all their wanderings continued to devote themselves to the study of Talmud.

Notarial Relations

Rebecca Winer and Sol Cohen

During the thirteenth century in the Latin Mediterranean, notaries were required to register all of the documents they drafted for their clients in a protocol that they kept for future reference. Currently in France, the medieval town of Perpignan was under the political control of the rulers of the Crown of Aragon (Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, the Balearics, Montpellier et al.). The thirteenth-century Crown of Aragon housed many prosperous and intellectually vibrant Jewish communities. The major Jewish urban center of Perpignan produced the highly original thinker Menahem ha-Meiri (who appears in Latin in the protocols of the 1270s on as Vidal Salamó Meir).

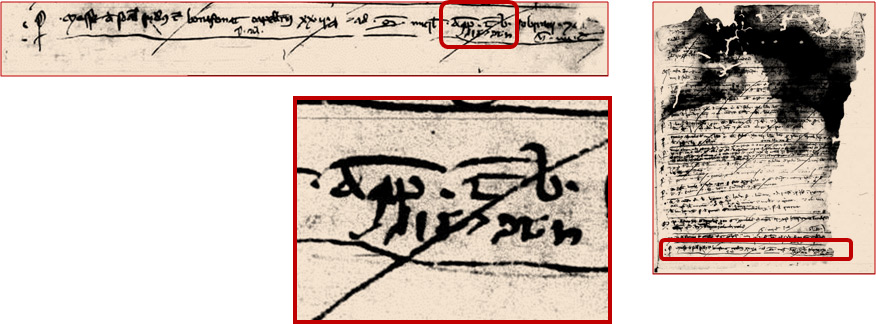

This image focuses on one of a series of radically abbreviated transactions in Latin: a loan that Bonafonat “Capellanus,” or “the chaplain,” made on 24 August 1261 to the Jew Mosse de Soal of twenty-two diners (pennies) to be repaid on the feast of the Archangel Michael, or Michaelmas, 29 September. This was a small loan made for a short time, only a month. Perhaps it concerned payment for Capellanus’s services as a Latin scribe; it is not possible to be certain. The 1261 protocol is one of only two registers with Hebrew notations; brief annotations appear after eight Latin transactions in 1261 and an additional two in a 1266 register.

The bottom right of this loan displays Mosse de Soal’s name in Hebrew: משה ד שואל. His Christian creditor may have asked Mosse to sign to support the transaction. Jews who lent money had been ordered by the king to take public oaths registered with their local notaries since 1241 at the latest. From the 1270s Hebrew notations are not found within the Latin registers. This 1261 register can thus possibly be read as transitional; a stage in the increasing familiarity and reliance of Jews on local Latin notarial culture. Local Jews regularly drafted Hebrew shetarot throughout the thirteenth century and well beyond. They also made transactions in Latin, not only debts and loans with Christians, but many other types of Jewish/ Christian transactions alongside various Latin agreements between Jews including those supporting Hebrew marriage contracts and death-bed inheritance declarations.

The Revival of Ciceronian Rhetoric

Rita Copeland

During 2012-13, the University of Pennsylvania Rare Book Collection acquired two important medieval manuscripts that show the revival of Ciceronian rhetorical study in the later Middle Ages.

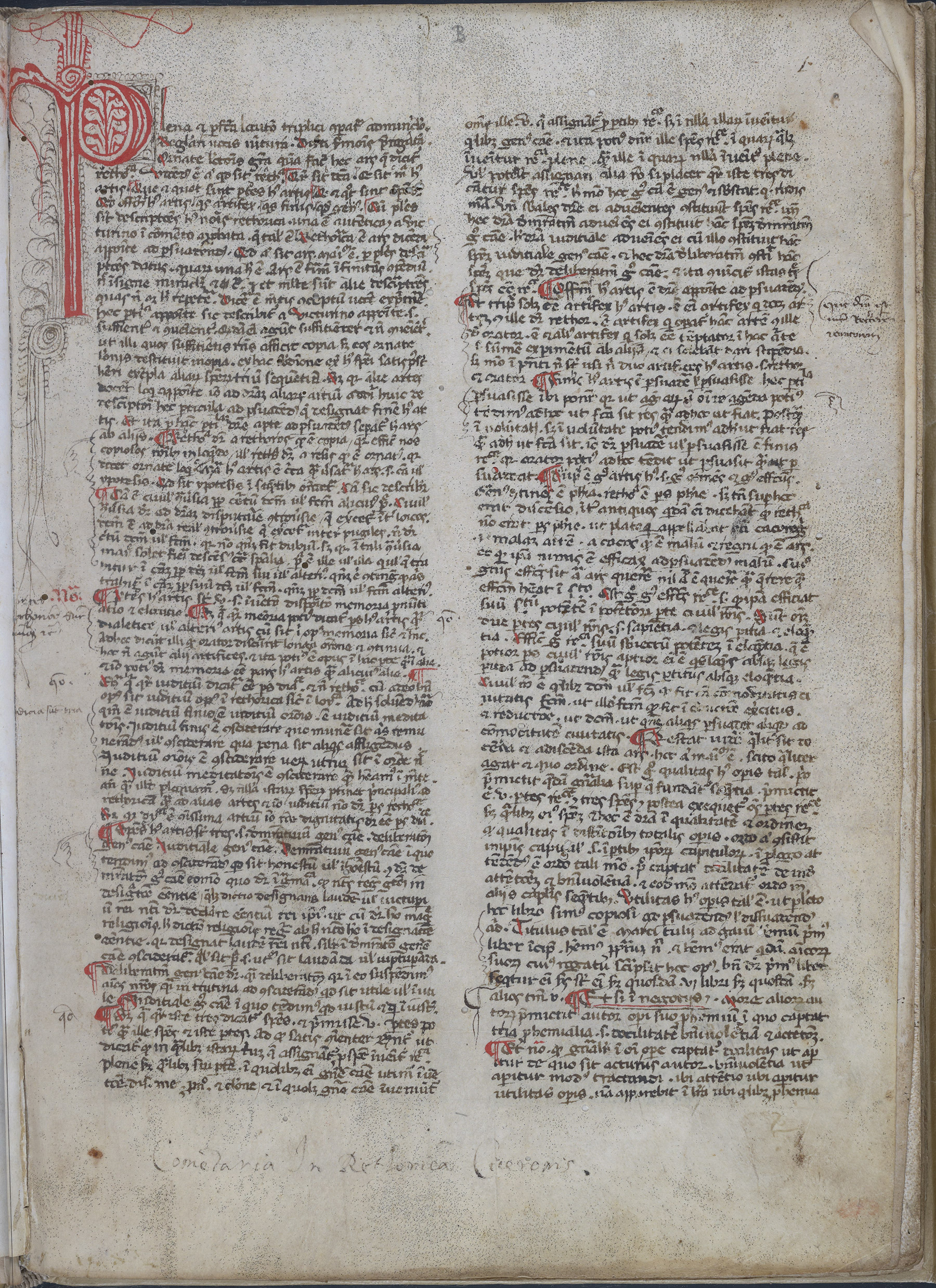

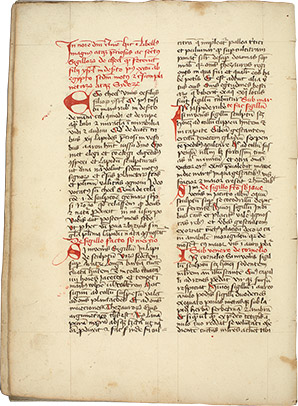

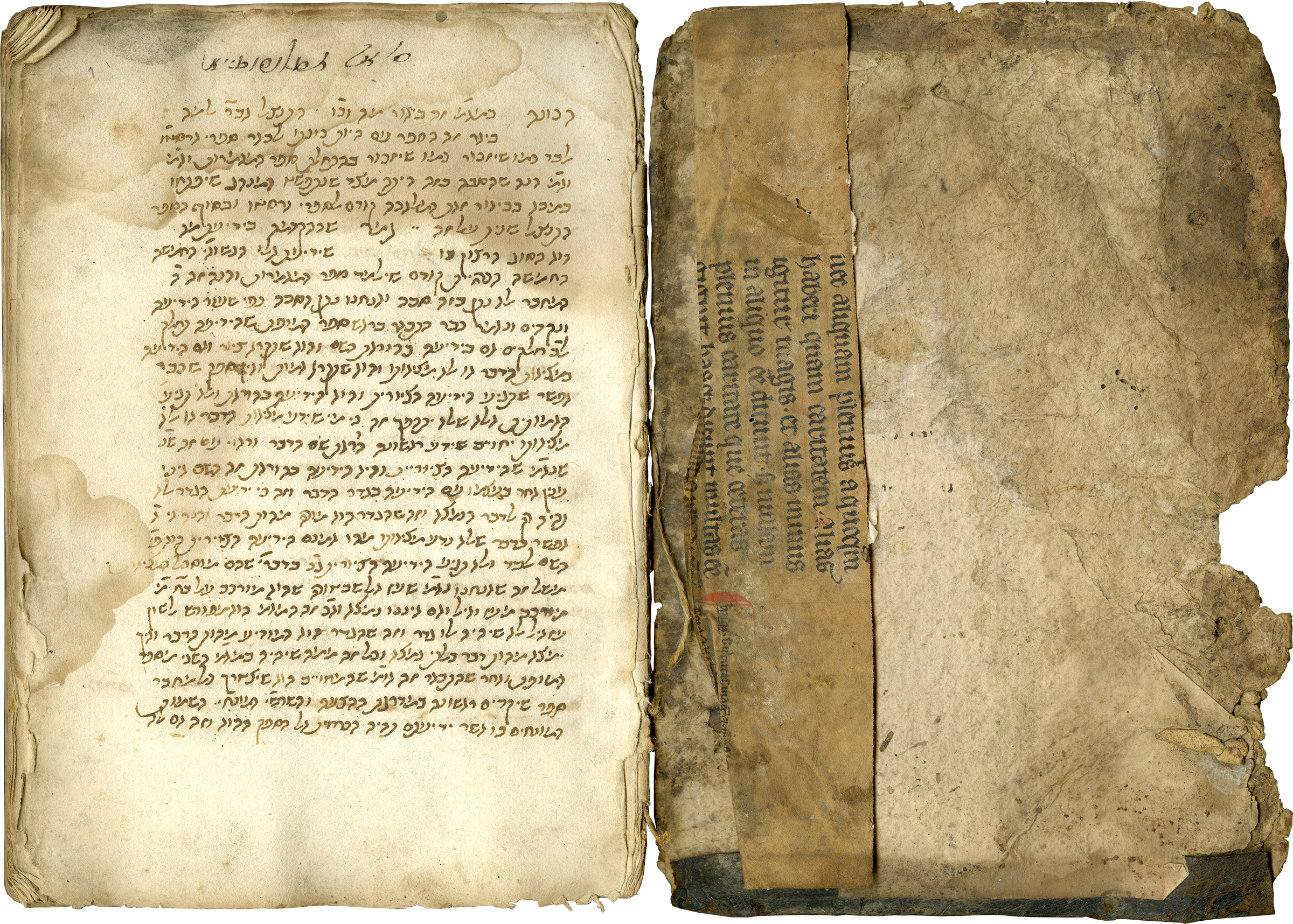

Ms. Codex 1629 - Commentaria ad Rhetoricam Ciceronis

The author of this commentary is unknown, although it is likely that he was a Dominican. The interest of the commentary lies in its position at the beginning of new commentative interest in the Ciceronian rhetorics after the dry years of the thirteenth century. While Cicero’s own youthful work, the De inventione, was much read during the early and central Middle Ages, the Rhetorica ad Herennium only really came into its own as a theoretical resource after about 1100, and from the second half of the twelfth century overshadowed the De inventione. But neither text received much new attention during the thirteenth century, because the study of eloquence was not part of the curriculum of university arts faculties. This does not mean that ancient rhetoric was not studied, but rather that most of the advanced academic contexts did not promote new commentaries on the older texts. The Ciceronian rhetorics remained relevant to the study of dictamen (the art of letter writing), but this field encouraged the production of new, practical textbooks rather than commentaries on the ancient texts. However, from the fourteenth century onwards, the religious orders, especially the Benedictines in Oxford and the mendicant studia in Italy, began to show great interest in Ciceronian rhetoric, and here the Ad Herennium was considered more useful perhaps because it is a complete course on the art. The Plena et perfecta commentary illustrates the course of study in mendicant circles and the expansion of rhetorical thought because of its application to preaching, business and bureaucratic needs, and arguing against heresy.

There is no edition of this commentary, which survives only in four manuscripts (two manuscripts in Italian archives, one held in the Bodleian Library, and one now held at the University of Pennsylvania).

The Plena et perfecta commentary gives us a clear picture of medieval glossing practices and education. It is a complete, free-standing commentary on the text, thus embodying the importance of that practice; and it is a working text, its annotations showing how rhetorical teaching was put to use for pragmatic purposes. The manuscript illustrates the practical value of rhetorical teaching outside the universities.

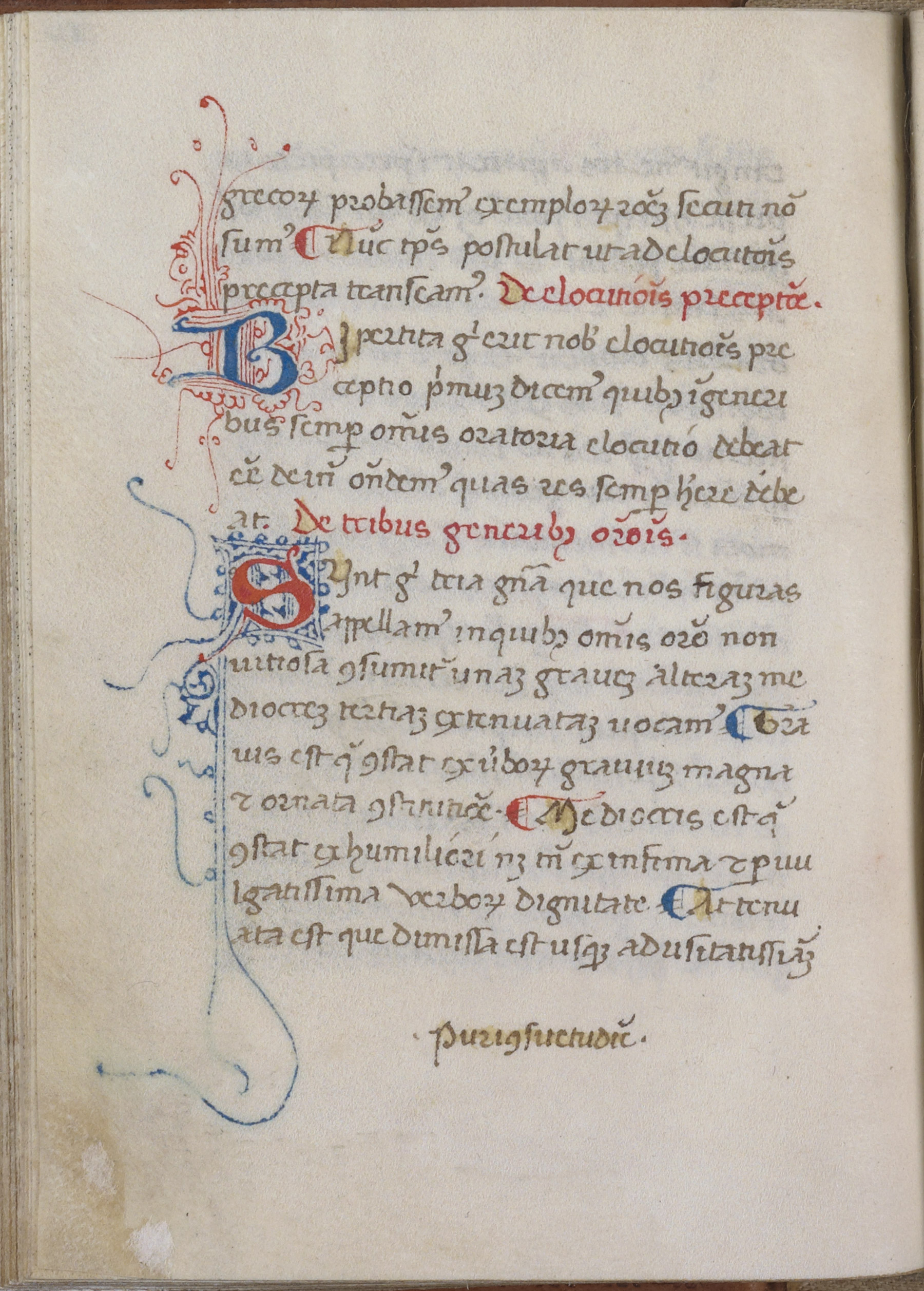

Penn’s Rare Book and Manuscript collection also acquired a complete copy of the Rhetorica ad Herennium itself, from fifteenth-century Italy: Ms. Codex 1630 - Rhetorica ad Herennium.

This manuscript gives a superb vista into late-medieval/early humanist practical uses of the Ad Herennium. As noted above, the Ad Herennium had begun to supersede the De inventione in popularity by the end of the twelfth century, and in this mid-fifteenth-century copy we can see some reasons for this shift: the Ad Herennium is a complete rhetoric, it teaches things that people needed to know, it has sections on memory and delivery and style as well as technical precepts for invention. All of these “value-added features” are brought together in a small, elegant but inexpensive, and convenient form in the fifteenth-century copy.

This Ad Herennium manuscript also offers a nice complement to the Plena et perfecta commentary. The Plena et perfecta is a Dominican product, an aid to learning the classical text for the purposes of preaching and even arguing against heresy (a special job of the Dominicans). The fifteenth-century Ad Herennium text, by contrast, is a portable book, probably designed for handy reference by either a preacher or some other kind of public speaker. It is the kind of object that could have been as valuable for a political speaker as for a religious preacher. Thus in these two manuscripts we have contrasting uses for the same material: close study of a lemmatic commentary in a volume that was not obviously designed to be portable; and the Ciceronian text itself in a portable form, without glossing but with handy rubrication for easy reference.

Commentaries on the Scientific and Philosophical Texts of Aristotle

S.J. Pearce

This substantial codex, copied in Germany in 1446 and consisting of 269 folios written in several Ashkenazi scribal hands, was recently acquired by the University of Pennsylvania through a gift made by the noted collector Lawrence J. Schoenberg and Barbra Brizdle Schoenberg. LJS 453 contains Hebrew translations of Arabic commentaries on the scientific works of Aristotle. Although it represents a fifteenth-century copy of the commentaries on works on various aspects of natural history, as well as on cosmology and meteorology, the texts themselves are the product of developments in intellectual history and tastes that flourished in earnest in the thirteenth century and continued into the fourteenth. As early as the second half of the twelfth century, Jewish readers living in regions of what are modern-day Spain and France began to translate Arabic-language scientific, philosophical and religious texts into Hebrew, with the consequence that these texts became available to a wider readership. The beginnings of this translation movement, which was consciously modeled on the ninth-century movement in the eastern Mediterranean to translate Greek-language texts into Syriac and Arabic, also led to the creation of a brand new technical vocabulary in Hebrew, since translators were often required to coin new terms for concepts in these fields that had not previously ever been discussed or written about in Hebrew.

The texts in this volume include: Solomon ibn Ayyub’s translation of Averroes’ commentary on De Caelo; translations by the noted Hebrew poet Kalonymos ben Kalonymos of the commentary on De generatione et corruptione and the Meteorologia; and Jacob ben Makhir’s translation of De Animalibus. The volume also contains Hebrew translations of Abraham ibn Ezra’s commentary on Psalms and fragments of Moses Maimonides’ Epistle to the Yemen. Taken together, these texts offer a coherent and complete, if not comprehensive, overview of the major intellectual and religious trends and debates that were current in thirteenth-century Spain and France. Beginning in the second half of the twelfth century, the father-and-son pair of translators, Judah and Samuel ibn Tibbon, began to adapt Arabic texts into Hebrew, often times at the request of particular communities with low levels of Arabic literacy but interest in reading texts of classical antiquity and the medieval Arabic commentaries upon them; this trend continued in northern Spain and southern France and allowed for the wide dissemination in the Jewish world of texts that were of scientific and dialectical-rationalist character.

If You Find an Engraved Stone: The Transmission of Science and Magic

Katelyn Mesler

Among the scientific writings of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages are treatises known as Lapidaries, short encyclopedic works on the properties of stones and minerals. One type of lapidary, exemplified by Marbode of Rennes’s famous Latin work On Stones, listed the name of each stone (often alphabetically), followed by details such as their color, where they are found, and any special “virtues” or powers that the stone possesses (such as the loadstone’s power of attraction or the bezoar’s reputation as an antidote for poison). Another type of lapidary was concerned with the symbolic meaning of the twelve biblical stones of the high priest’s breastplate and the heavenly Jerusalem.

The Techel/Azareus Complex, pictured here, is a Latin lapidary in which engravings of astrological symbols are said to imbue the stones with powers. The prologue (in red) offers an origin story for the text and the stones it describes: “In the name of the Lord, Amen. This is Cheel’s great, precious, and secret little book of the sigils that the children of Israel made in the desert after their departure from Egypt, in accordance with the motion and course of the planets and constellations.” Entries for the stones begin with the phrase “If you find…” and then describe in detail the images, based largely on Greco-Roman astrological iconography, that one might find engraved on a stone. The reader is then instructed on the special virtues and magical uses of any stone that meets the description.

The origins of the Techel/Azareus Complex remain a mystery, but the text has roots and parallels in the Greek and Arabic lapidary traditions. The oldest identified copy of this Latin lapidary dates to the twelfth century. In the course of the next few centuries, it was translated into several vernacular languages and became one of the most widely circulated and cited of all medieval lapidaries. Notably, the text was also translated into Hebrew (via Anglo-Norman) in the thirteenth century. By the end of the Middle Ages, two more Jewish versions had appeared: one written in Italian in Hebrew characters and a second Hebrew version (via Castilian and Catalan) that may have originated outside the Latin tradition. The lapidary in all its versions is part of a wider movement in the Middle Ages to transmit and translate scientific works, bridging not only ancient and medieval traditions but also cultural, linguistic, and religious ones.

The ‘Amude Golah (Pillars of Exile) of R. Isaac of Corbeil

Judah Galinsky

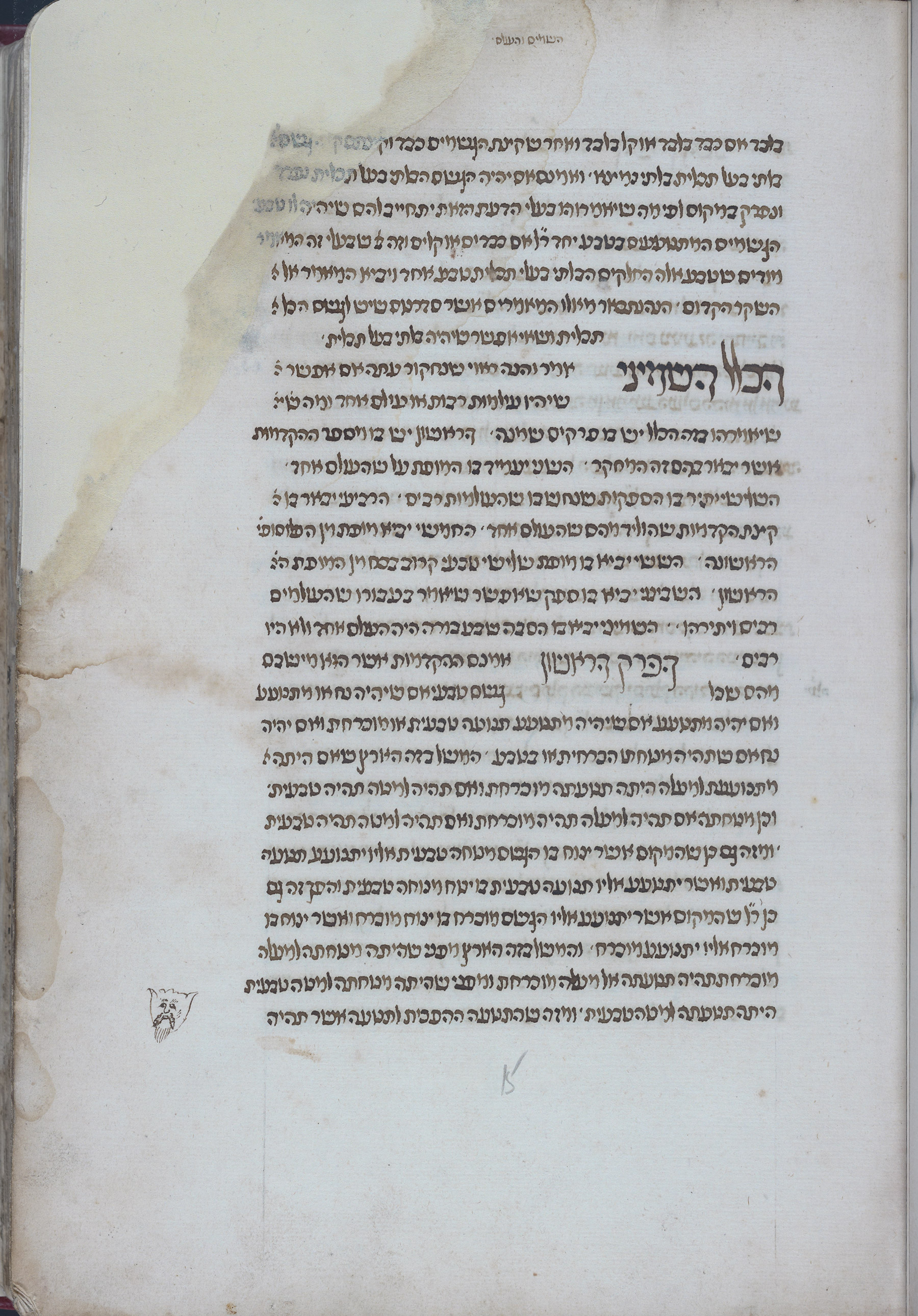

The ‘Amude Golah (Pillars of Exile) of R. Isaac of Corbeil was completed circa 1278 just a few years prior to the author’s death in the spring of 1280. This accessible halakhic work, written with the intent of reaching a broad reading audience, was extremely popular during the later Middle Ages as the numerous extant manuscripts can attest (close to 200 mss.). With time the work became known as the Sefer Mitsvot Katan \[The Short Book of Commandments\] or Semak. Shortly following its distribution the author’s younger contemporary and even more famous townsman, R. Peretz of Corbeil, appended his scholarly glosses to the Semak. Almost all surviving manuscripts of the work include these learned glosses.

One of the most difficult textual problems that one encounters in studying Isaac of Corbeil’s work relates to Peretz’s glosses. Copyists of the work from the 13th century onwards had great difficulty in differentiating between Isaac’s original work and the later material added by Peretz. This led to situations where Peretz comments were frequently integrated into the body of the work while at times Isaacs’ thoughts were relegated to the glosses. The task of reconstructing Isaac’s original work became feasible only with the discovery of the version found in British Library Add. 11639 (1056 in Margoliouth Catalogue) known as the Northern French Hebrew Miscellany (reproduced here from the Falter Facsimile Editions).

This late thirteenth-century manuscript was copied by a certain Benjamin the Scribe. The colophon lacks an exact date however Malachi Beit-Arie has argued, based on internal calendar evidence, that the 746 page manuscript was copied during the years 1279 –1282\. I would add that in his copy of the Semak, Benjamin constantly refers to R. Isaac of Corbeil with the abbreviation “mem reish shin” moreinu shechye—my master may he live \[a long life\]. This would indicate that at the time that Benjamin transcribed the book, Isaac was still alive. Since Isaac died in the spring of the year 1280 this would further strengthen Beit-Arieh’s dating for the copying of the entire manuscript. It is true that not always does the “earliest” surviving manuscript turn out to be significant; however in this case it does. To the best of my knowledge this is the only version of the Semak to reach us that does not include any of Peretz’s glosses. It is reasonable to assume that at the time the work was copied Peretz had not yet written his glosses, and definitely had not circulated them. Thus any attempt to reconstruct Isaac of Corbeil’s original Semak would have to begin with this unique manuscript.

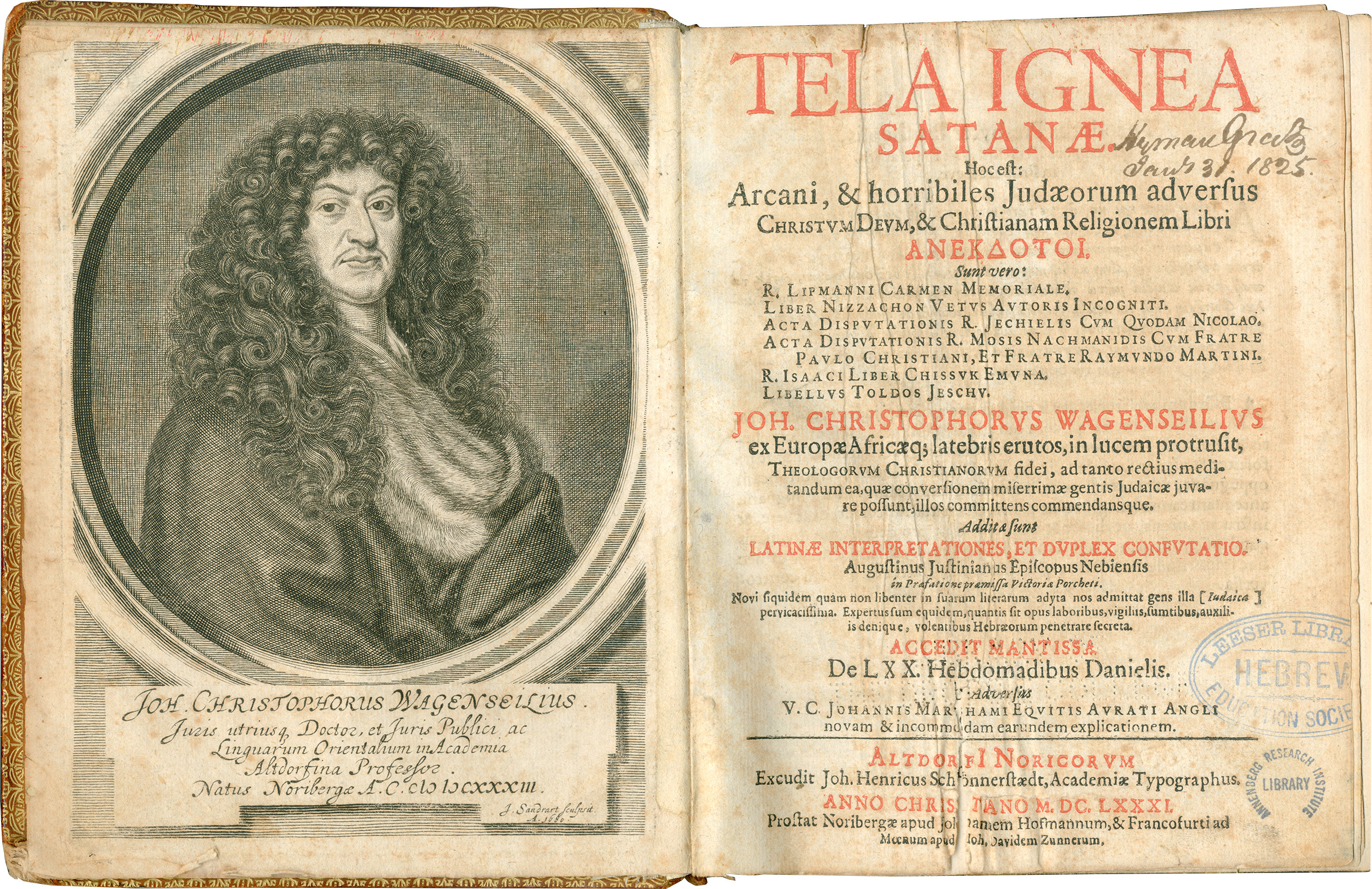

An Interfaith Dialogue of Flaming Arrows: Johan Christoph Wagenseil and his Tela Ignea Satanae

Piero Capelli

Johann Christoph Wagenseil (b. Nuremberg, 1633; d. Altdorf, 1705) earned his Dr.Phil. in 1665 from Altdorf Academy, the forerunner of the University of Altdorf, and taught history, law and Near Eastern languages from 1668 until the end of his life. His book Tela Ignea Satanae (The Flaming Arrows of Satan, Altdorf, 1681), from which the portrait is taken, is an anthology of Jewish anti-Christian polemics containing many of the most important medieval and early modern Jewish anti-Christian polemics: the Toledot Yeshu, the Hebrew accounts of the 13th century Paris Talmud trial and the Barcelona disputation, the Sefer Nizzahon Yashan, and Isaac Troki’s Hizzuq Emunah. These appeared here in their first printed editions, with Latin translations and scholarly commentary Wagenseil’s historical and philological awareness in the book are acute and prescient; but it was openly inspired by pointed anti-Jewish intent, as is evident from its title, in which the “flaming arrows of Satan” (cf. Ephesians 6:16) are Jewish ones aimed against Christendom.

After publishing Tela Ignea Satanae, Wagenseil came into contact with Jewish scholars. This made him aware of the hardships of the status of the Jews in Europe and of the absurdity of the accusations of ritual murder. Toward the end of his life, according to the historian Peter Blastenbrei, Wagenseil “began to sketch a design for peaceful coexistence of Jews and Christians through legal demarcation, humane treatment of the minority, and closer mutual acquaintance.” He took a stand against the ritual murder libel in an essay called “Judæos non Uti Sanguine Christiano” (“The Jews Do Not Make Use of Christian Blood”) published in his book Benachrichtigung wegen einiger die gemeine Jüdischheit betreffenden wichtigen Sachen (Information against Some Important Things Concerning the Jewish Community, Leipzig, 1705). At the same time, he remained convinced that the Jews blasphemed against Jesus, Mary and Christian dogmas and symbols (Denunciatio Christiana de Blasphemiis Judæorum in Jesum Christum, A Christian Condemnation of Jewish Blasphemies against Jesus Christ, Altdorf, 1703), and promoted Christian missionizing to the Jews (Hoffnung der Erlösung Israels, Hope in Israel’s Redemption, Leipzig, 1705).

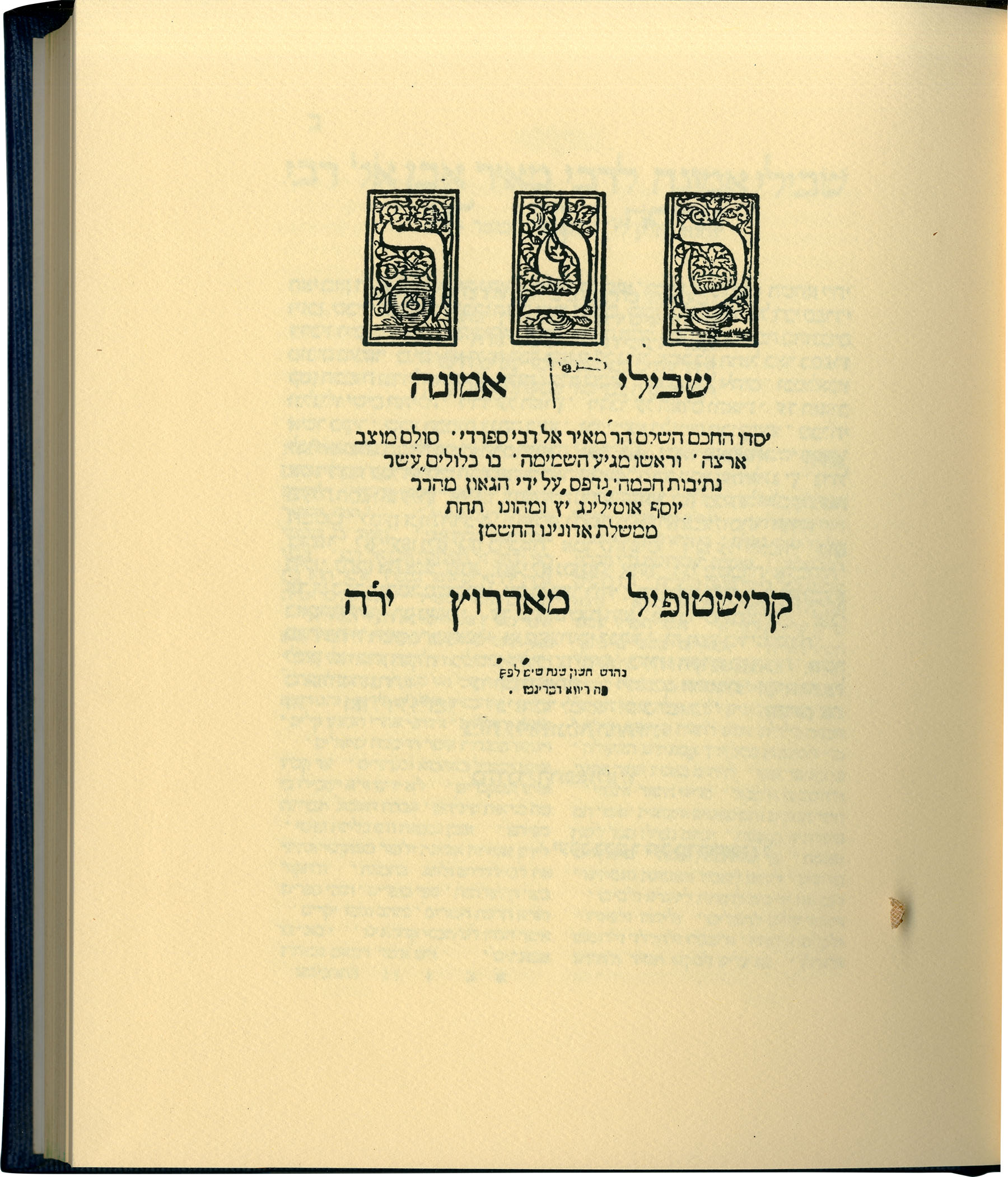

Meir b. Isaac Aldabi’s Paths of Faith (Shevile Emuna)

Uri Shachar

In 1346 or thereabout Meir Aldabi, a Toledan polymath, immigrated to Jerusalem where he resided until his death fourteen years later. During this final period of his eventful life, Aldabi completed his magnum opus, The Paths of Faith \[Shevile Emunah\]—a comprehensive ‘encyclopedia’ which covers many of the major trajectories in late medieval Jewish natural philosophy, theology, and mysticism. Aldabi’s work, which is both far reaching and concise, enjoyed immediate and long lasting success. Both individual chapters (especially paths four and five) and the unified work were disseminated widely. The Library at the Katz Center holds a facsimile of the earliest printed edition of this pre-modern best seller, produced at Riva di Trento in 1558.

Despite its popularity among a variety of circles and over the course of several centuries, The Paths of Faith has received scant attention in modern scholarship. Previous generations of intellectual historians saw in this work a clumsy, unoriginal concoction of earlier theoretical or pre-existing encyclopedic material. Closer attention, however, to the ways in which Aldabi put to use the material he reproduced reveals that, in fact, he undertook a unique, herculean effort to harmonize diverse and often contradictory intellectual tendencies that shaped the Jewish contemplative landscape of his times, into one spiritual program. As such, The Paths of Faith does not only list, but in fact, reconciles and hence redefines rationalist, conservative, and mystical energies that had been pulling in different directions.

One such intellectual impulse that Aldabi accommodates stems from a tradition that he must have encountered while in Jerusalem. The tenth and ultimate chapter of the book, about the Redemption, features a processed version of a homily that was penned by an anonymous scholar who immigrated to Acre in the beginning of the thirteenth century. By invoking a messianic framework, this homily reflects on questions of conquest and possession of the Holy Land, in a way that places it in dialogue with contemporaneous Christian and Muslim holy war literature. What is more, this text became the rhetorical and ideological backbone for a number of such homilies subsequently composed by Jews in the Near East under Frankish and Mamluk rule. The Paths of Faith, therefore, encompasses many important trajectories that became manifest through cultural, intellectual, and linguistic contacts between Jews and their neighbors in the late medieval Mediterranean.

Las Cantigas de Santa Maria: Miraculous Stories of Horror and Conversion

Kati Ihnat

The Cantigas de Santa Maria is a collection of over four-hundred short accounts of miracles performed by the Virgin Mary interspersed with songs of praise, produced in the court of Alfonso X of Castile (r. 1252-1284). This image is from one of four extant codices of the collection produced in the 1270s and 80s, Escorial MS T.I.1, the ‘códice rico,’ as it is known by scholars due to its luxurious nature; one of a small number of facsimiles of this stunning manuscript is held by the University of Pennsylvania library. Almost all the poems in medieval Galician are illustrated with a full-page illustration and are also set to music. Intended to establish Alfonso as Mary’s royal champion, the volumes constitute an important testament of the cultural vibrancy of the Castilian court, its development of music, literature and art, as well as its engagement with Jewish and Muslim cultures.

The miracle story shown here nevertheless provides a complicated picture of inter-cultural relations. It begins with a debate between a Jewish al-faquin—a sage or doctor, here shown in an apothecary—and Merlin, the legendary prophet and magician of Arthurian lore. Merlin defends the Virgin birth and the Incarnation, while the Jew firmly denies it. Faced with the Jew’s stubborn resistance to his arguments, Merlin finally calls upon the Virgin to perform a miracle in order to show the Jew the error of his ways. Mary complies by having the Jew’s son born with his head on backwards. In his horror at the deformed child, the Jewish father wishes to destroy it, but Merlin takes the boy and uses him to convince other Jews of the truth of the Christian message, leading to baptism, as shown in the final scene.

The curious story reflects the integration of contemporary literary and devotional trends, as popular secular literature was incorporated into a long-standing legendary tradition of depicting Jewish animosity towards the Virgin. Additionally, it suggests knowledge of the public debate organised by James I, King of neighbouring Aragon, between prominent figures from the Jewish and Christian communities in 1263. But rather than encourage such disputations, the story here, like many others in the volume, seems rather to promote the intercessory role of the Virgin in converting Jews to Christianity. The story and the collection in which it is found therefore illustrate how the tremendous growth of the cult of the Virgin Mary helped shape ideas about Jews and Judaism, as well as relations between Jews and Christians, in thirteenth-century Iberia.

Commentary on Averroes’ Middle Commentaries on the Isagoge of Porphyry, the Categories and De Interpretatione of Aristotle

Charles Manekin

It is hard to overestimate the importance of the first three books of the logical canon known as the Organon—the Isagoge (Introduction) of Porphyry of Tyre, and the Categories and the De Interpretatione of Aristotle—for medieval intellectual life. Already in late antiquity these books were an essential part of the medical curriculum, and all medieval physicians, Muslim, Jewish, and Christian, were expected to have mastered their comments. Students of scientific subjects commenced their studies with either these particular books, or at least their subject-matter, e.g., how we categorize the world we experience, what sorts of properties distinguish natural kinds from each other, and how we combine our concepts to form judgments about the world.

The first three books of the Organon were never translated into Hebrew. Instead, paraphrases of them by the 12th century Muslim philosopher Averroes (Ibn Rushd) were translated from the original Arabic into Hebrew in Naples by Jacob Anatoli in 1232 (together with the next two books of the Organon, the Prior and Posterior Analytics, on syllogistic inference and scientific demonstration, respectively.) Averroes’ paraphrases or “Middle Commentaries” of the first three works are extant in over eighty Hebrew manuscripts (and likely more), making them, according to the great literary historian and bibliographer, Moritz Steinschneider, the most popular works in Hebrew written by a non-Jew. They were commented upon by Jewish savants such as Levi Gersonides in the fourteenth century, and Judah Messer Leon in the fifteenth century.

The particular commentary found in the Schoenberg Collection (LJS 229) is anonymous and has not yet been studied. No other copy of it exists, to my knowledge, but the section on the De Interpretatione is found in Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Cod. hebr. 46. The commentator refers often to the logical writings of the 10th century Muslim philosopher, Alfarabi, some of which were translated into Hebrew in the late 12th and early 13th century. He also refers to the Arabic version of Averroes’ text. But, most interestingly, he cites and criticizes at least once the interpretation of “my teacher, R. Levi,” which a cursory comparison of the manuscripts reveals to be Gersonides. If this is correct, then the author of the commentary in LJS 229 was another member of Gersonides’ “school,” where students read texts with Gersonides and occasionally wrote their own glosses as comments, as has recently been studied by Prof. Ruth Glasner of Hebrew University. Since Gersonides also refers to the Arabic version of Averroes, this manuscript sheds additional light on the methodology employed by members of Gersonides’ circle.

As interesting as the anonymous commentary is in itself, the physical codex sheds light on the intellectual life of Provence in the second half of the 15th century. One finds the following statement of ownership in Latin: “Iste liber est meus mestre Benustruc\[?\] Avidor.” This individual may be identified with the 15th century ProvenC’al savant, Avigdor Benastruc, who translated into Hebrew around 1490 the anonymous French Romance of Belle Maguelone, and who wrote a manuscript that included works by the Provencal Jewish scholar, Isaac Nathan, the composer of the first Hebrew concordance of the Bible. If that is the case, it shows that as late as the late fifteenth century, if not later, basic works in Aristotelian logic were studied in Provence, and the influence of Gersonides and his students was still very much felt.

Selected Bibliography

-

Alfonso, Esperanza. Islamic Culture Through Jewish Eyes: Al-Andalus from the Tenth to the Twelfth Century. (London; New York: Routledge, 2008).

-

Alfonso, Esperanza, et al. (editors). Biblias de Sepharad = Bibles of Sepharad. ([Madrid, Spain]: Biblioteca Nacional de España, [2012]).

-

Baumgarten, Elisheva. Mothers and Children: Jewish Family Life in Medieval Europe. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004).

-

Baumgarten, Elisheva. “A Tale of a Christian Matron and Sabbath Candles: Religious Difference, Material Culture, and Gender in Thirteenth-Century Germany.” Jewish Quarterly Review, vol. 20, no. 1 (2013), pp. 83–89.

-

Capelli, Piero. Il male: Storia di un’idea nell’ebraismo dalla Bibbia alla Qabbalah. (Firenze: Società Editrice Fiorentina, 2012).

-

Copeland, Rita. Rhetoric, Hermeneutics, and Translation in the Middle Ages: Academic Traditions and Vernacular Texts. (Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

-

Copeland, Rita and Sluiter, Ineke (editors). Medieval Literary Theory: Grammatical and Rhetorical Traditions, A.D. 300–1475. (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

-

Elias, Jamal (editor). Key Themes for the Study of Islam. (Oxford, UK: Oneworld, 2010).

-

Elias, Jamal. Aisha’s Cushion: Religious Art, Perception, and Practice in Islam. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012).

-

Fidora, Alexander and Lutz-Bachmann, Matthias (editors). Juden, Christen und Muslime: Religionsdialoge im Mittelalter. (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2004).

-

Fidora, Alexander, et al. The Multiple Meanings of Scripture: The Role of Exegesis in Early Christian and Medieval Culture. (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2009), pp. 273–290.

-

Galinsky, Judah. “Ashkenazim in Sefarad: The Rosh and the Tur on the Codification of Jewish Law.” The Jewish Law Annual, vol. 16 (2006), pp. 3–23.

-

Galinsky, Judah. “The Significance of Form: R. Moses of Coucy’s Reading Audience and His Sefer ha-Mizvot.” AJS Review, vol. 35 (2011), pp. 293–321.

-

Hollender, Elisabeth. Piyyut Commentary in Medieval Ashkenaz. (Berlin; New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2008).

-

Hollender, Elisabeth. Qedushta’ot des Simon b. Isaak nach dem Amsterdam Mahsor: Übersetzung und Kommentar. (Frankfurt/Main: P. Lang Verlag, 1994).

-

Kanarfogel, Ephraim. Jewish Education and Society in the High Middle Ages. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1992).

-

Kanarfogel, Ephraim. The Intellectual History and Rabbinic Culture of Medieval Ashkenaz. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2012).

-

Karras, Ruth. Unmarriages: Women, Men, and Sexual Unions in Medieval Europe. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012).

-

Karras, Ruth. Sexuality in Medieval Europe: Doing Unto Others. 2nd edition. (New York; London: Routledge, 2012).

-

Krinis, Ehud. “The Arabic Background of the Kuzari.” Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy, vol. 21, no. 1 (2013), pp. 1–56.

-

Krinis, Ehud. God’s Chosen People: Judah Halevi’s ‘Kuzari’ and the Shi’i Imam Doctrine. (Tournhout: Brepols, 2013).

-

Manekin, Charles. The Logic of Gersonides: A Translation of “Sefer ha-Heqqesh ha-Yashar” (The Book of the Correct Syllogism) of Rabbi Levi ben Gershom, with Introduction, Commentary, and Analytical Glossary. (Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1992).

-

Manekin, Charles (editor). Medieval Jewish Philosophical Writings. (Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

-

Mesler, Katelyn. “The Lapidary of Techel on Engraved Stones and Its Medieval Jewish Appropriations.” Aleph: Historical Studies in Science and Judaism.

-

Mesler, Katelyn. “The Three Magi and Other Christian Motifs in Medieval Hebrew Medical Incantations: A Study in the Limits of Faithful Translation.” In Latin-into-Hebrew: Studies and Texts, edited by Resianne Fontaine and Gad Freudenthal, vol. 1. (Leiden: Brill, 2013).

-

Reiner, Avraham. Rabenu Tam u-vene doro: Kesharim, Hashpa’ot ve-Darkhe Limudo ba-Talmud. (Israel: n.p., 2002).

-

Reiner, Avraham (editor). Ta-Shema: Mehkarim be-Mada’e ha-Yahadut le-Zikhro shel Yisrael M. Ta-Shema, 2 vols. (Alon Shevut: Tevunot, Mikhlelet Hertsog, 2011).

-

Winer, Rebecca. Women, Wealth, and Community in Perpignan c.1250–1300: Christians, Jews, and Enslaved Muslims in a Medieval Mediterranean Town. (Surrey, UK: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2006).

-

Winer, Rebecca. “Conscripting the Breast: Lactation, Slavery, and Salvation in the Realms of Aragon and the Kingdom of Majorca, c. 1250–1300.” Journal of Medieval History, vol. 34, issue 2 (June 2008), pp. 164–184.

Contributors

-

Elisheva Baumgarten - Bar-Ilan University / Rose & Henry Zifkin Teaching Fellowship

-

Piero Capelli - University of Venice / Primo Levi Fellowship

-

Mordechai Z. Cohen - Professor of Bible and Associate Dean, Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies, Yeshiva University

-

Sol Cohen - Senior Researcher, Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, University of Pennsylvania

-

Rita Copeland - University of Pennsylvania / Ruth Meltzer Fellowship

-

Alexander Fidora - Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

-

Judah Galinsky - Bar-Ilan University / Charles W. & Sally Rothfeld Fellowship

-

Elisabeth Hollender - Goethe University / Nancy S. & Laurence E. Glick Teaching Fellowship

-

Kati Ihnat - Queen Mary, University of London / Ivan & Nina Ross Family Fellowship

-

Ephraim Kanarfogel - University Professor of Jewish History, Literature and Law, Yeshiva University

-

Ruth Karras - University of Minnesota / Golub Family Fellowship

-

Ehud Krinis - Hebrew University / Dalck & Rose Feith Family Fellowship

-

Charles Manekin - University of Maryland / Ellie and Herbert D. Katz Distinguished Fellowship

-

Katelyn Mesler - Northwestern University / Erika A. Strauss Teaching Fellowship

-

S.J. Pearce - New York University / Louis Apfelbaum and Hortense Braunstein Apfelbaum Fellowship

-

Rami Reiner - Ben-Gurion University / Samuel T. Lachs Fellowship

-

Uri Shachar - University of Chicago / Ella Darivoff Fellowship

-

Rebecca Winer - Villanova University / Maurice Amado Foundation Fellowship

Special thanks

Special thanks to Leslie Vallhonrat, Manager of the Penn Libraries’ Web Unit, for her creativity, expert web design, and hard work, to Amey Hutchins for her expert advice and help with the Lawrence J. Schoenberg Collection of medieval manuscripts, and to Dr. Bruce Nielsen, Josef Gulka, John Pollack, Elton-John Torres, and Chris Lippa for their scanning labors, their enthusiasm and their overall support.